Music is at the heart of creating identity and culture across the black diaspora. It colours everyday life, acting as a source of inspiration for creative output and informing academic approaches to cultural theory. This is the case for artist and filmmaker, Arthur Jafa. Incentivised by the rich culture of music across the Black diaspora, Jafa’s first solo exhibition in London’s Sadie Coles HQ, ‘Glas Negus Supreme’, takes his practice one step further as he explores the power of music through the use of oil paints alongside his signature retouched films and photography.

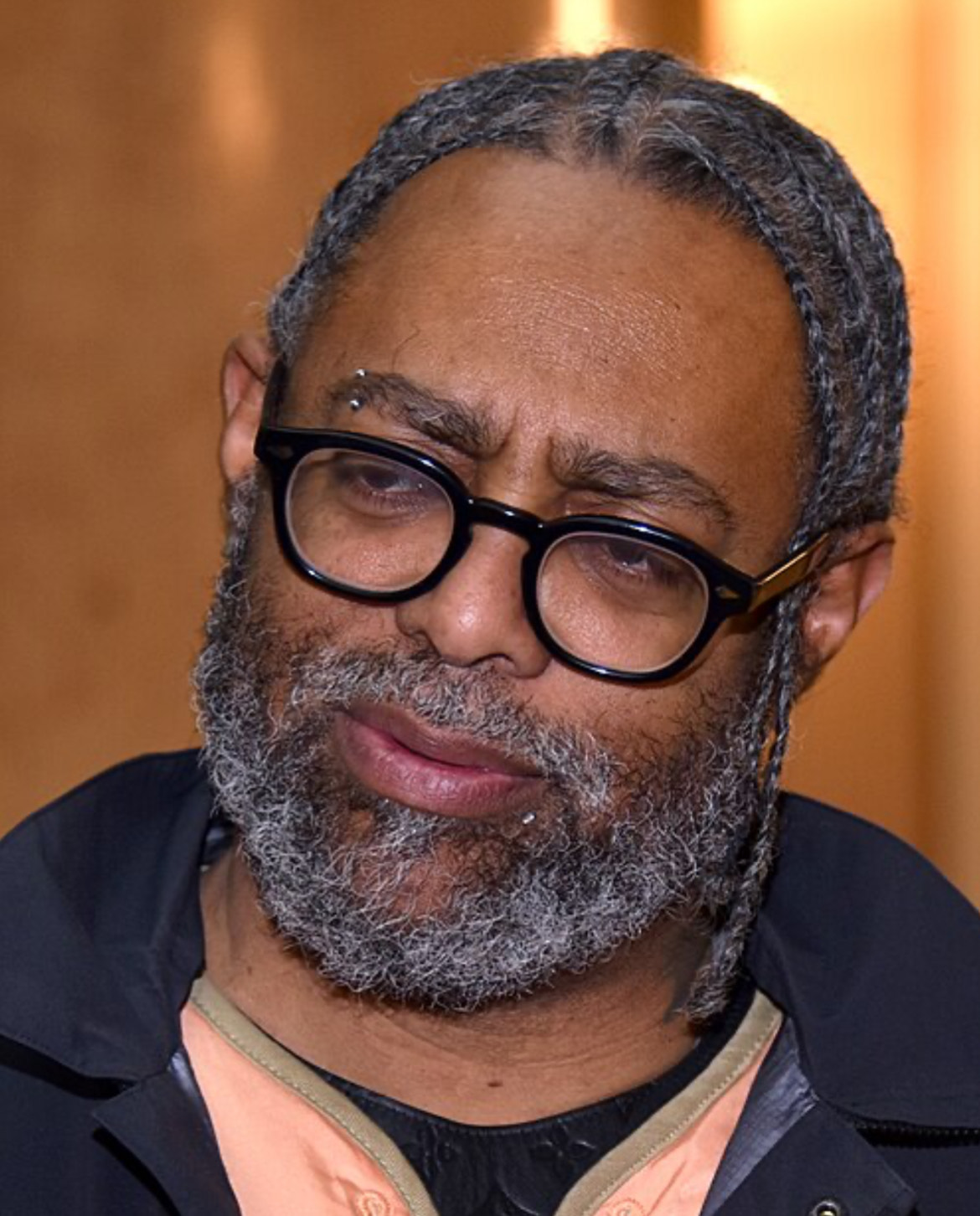

As an artist and filmmaker, born and raised in Mississippi, Jafa’s work is experimental in its splicing and reconstruction of key figures and moments in Black American music history and across the diaspora. His creative portfolio is vast; with notable credits on Solange’s ‘Cranes In The Sky’, a Sundance award for his work on ‘Daughters In The Dust’ and representation by Gladstone Gallery. Overall, Jafa’s three decade long career is expansive but revolves around his specific niche. Each piece and film is a commentary on the complexities of Black music in the contemporary space. Yet, ‘Glas Negus Supreme’ is a testament that Jafa’s artistic explorations are far from complete.

Sadie Coles HQ’s Kingly Street gallery seems to be the perfect space to house the exhibition with its industrial architecture somehow evading the characteristic sterility of many commercial galleries. Instead, the space seems to embrace the unconventional eccentricity of Jafa’s pieces. Upon entry, Jafa’s ‘I just want our love to last’ occupies an entire wall. Black faces, manga excerpts and logos exist in a collage seemingly shrouded under the obscured light of the eclipse depicted in the upper corner. This creates a sense of transcendent meaning for the use of the black and white that ties the piece together. Each image seems to depict different eras in time, some showcasing musicians mid performance and others still shots from films. Altogether, this wallpaper piece ties the exhibition together as an introduction to the vast histories and forms portrayed within the space.

The exhibition includes two of Jafa’s film pieces, ‘Structural Mutiny_Prince’ and ‘Townshend’. Both short films heavily contrast each other. ‘Structural Mutiny_Prince’ is a colourful and dynamic homage to the music legend. Playing on a 12 minute and 52 second loop, the film features the star’s reception from his fans in the background, cheering as he dances across the stage. In contrast is ‘Townshend’, a 33 minute film of Peter Townshend, leader of English rock band, The Who. Townshend’s silently sustained eye contact with the camera is at first unsettling, then mournful and at some points almost comforting. The black and white shot captures the subtleties of his facial expressions, sometimes almost frozen and others sped up and frenzied thanks to Jafa’s editing. This prolonged silence is particularly enrapturing considering the lively, voracious performances that Townshend had given as a rock star.

Much like the dualities of ‘Townshend’ and ‘Structural Mutiny_Prince’, the exhibition as a whole is a commentary on varying emotional and visceral responses to music, performance and stardom. ‘Drapetomania’ is particularly interesting. A term that was used to describe “the mental illness” that caused slaves to run away, the still frames of the collage are frenzied and blurred. The central figure’s eyes convey a sense of mania that, in the context of the exhibition, can be interpreted as a result of the music or party that surrounds him. The use of electric blue for two of the many logos overlaid on the image immediately drew the eye, creating a visual contrast to the black and white collage behind them. Jafa’s use of black and white imagery with hints of colour are present throughout the exhibition, seeming to create an atmosphere of timeless equality between all the images on display. The artist’s expansive perspective of music is not bound by modernism or antiquity. Instead their visual interest lies in the textural uniqueness or experimental editing of each as seen in ‘And Live Iggy and Patti’ or ‘Miss Tate’.

Potentially the standout pieces of the exhibition were found in the smaller, latter space of the gallery. ‘Kiss_NLove’ and ‘Foxy Lady’ are congruous in nature with the exhibition but also clear outliers. In form, both deviate from the established use of found imagery, photography and film that fill the majority of the exhibition. Instead they are oil paint on linen. This invites a new sense of tangibility to Jafa’s practice, bringing to mind thoughts of him considering where to lay his brush to create the intended image rather than overlaying photographs. ‘Foxy Lady’ depicts Foxy Brown, mid strut on stage. Her movement seems fluid and determined and the canvas is filled with colour, yet another deviation from the muted tones of the other paintings. Although ‘Kiss_NLove’ does stick to the central theme of black and white and with similarly blurred texture, the image itself is intimate in nature. The close up of an impassioned kiss sparks the imagination to figure out the wider contexts of this affection. Like many of Jafa’s pieces throughout the exhibition and his catalogue, the interpretations of this intimate moment are left entirely up to the viewer to decipher.

‘Glas Negus Supreme’ is a reflective yet experimental view of the ever evolving musical landscape. Jafa’s style in how he creates and portrays each work is what truly stands out as a viewer. He pushes the bounds of musical commentary while paying homage to legendary musicians. However, he is not stuck in the past as he finds new and visually interesting ways to acknowledge the power of music. While ‘Foxy Brown’ is a personal favourite, ‘Townshend’ is deceptively brilliant in its push to confront human emotion. Overall, Arthur Jafa’s ‘Glas Negus Supreme’ is an exhibition that is not to be missed.