The year 2025 marked a definitive turning point for electronic dance music (EDM) and house music in Nigeria. No longer a niche subculture confined to the fringes of Lagos nightlife, the scene exploded into a vivacious industry, recording a staggering 403% growth in engagement and consumption. This electronic renaissance was fueled by a unique blend of indigenous sonic experimentation, the influx of global heavyweights, and, importantly, a dedicated ecosystem of collectives that prioritised community over commercialism.

In 2025, the Nigerian house scene was defined by collectives. These groups acted as curators, safe spaces, and tastemakers, each carving out a distinct identity.

The rise of Group Therapy (GT) is one of the most significant case studies in the professionalisation and global scaling of the Nigerian electronic scene, or even any scene at all. Group Therapy started in 2023, and by 2025, it evolved from a series of niche underground gatherings into a cultural bridge for major global entries, including Boiler Room and Keep Hush. Under Aniko’s leadership, Group Therapy hosted the most impressive range of raves in 2025, from the impromptu “SMWR” editions in multi-storey car parks in Lagos Island to “KlubAniko” at the sophisticated Royal Box Centre in Victoria Island, and managed to maintain top quality across board. Group Therapy’s lineup for every 2025 edition paved the way for a more diverse roster of DJs – including many women, nonbinary, and intersex artists – to play prominent roles in the 2025 rave cycle. However, the collective's most significant achievement was the successful attraction of a record number of renowned international DJs to its Lagos-based editions.

As one of the longest-running house music residencies in Lagos, Element House (under the Spektrum banner, run by Ron and DelNoi) provided the necessary stability for the scene. Their monthly editions remained the "gold standard" for consistency. The 2025 rave calendar kicked off with a visually stunning Element House edition, courtesy of artist Bidemi Tata. This event marked the beginning of a sustained partnership between the organisers and the University of Lagos-trained artist. Throughout the rest of the year, they continued to collaborate with Bidemi Tata to refine their visual narrative, transforming each subsequent event into a sophisticated, high-concept, and fully immersive experience. In 2025, Element House achieved two significant milestones. Firstly, it solidified its position as the scene's "reliable giant," providing a predictable, safe, and carefully curated environment through its monthly residency. Secondly, Element House successfully cornered the economic power of the scene. By catering to a demographic of ravers who prioritised comfort over the raw atmosphere of a warehouse, they legitimised house music to corporate Nigeria. It is fair to claim that this appeal helped secure sponsorships that were out of reach for more underground rave events. The Element House lineup for every episode was also impressive, with them closing the year with a 2-hour Francis Mercier set.

Monochroma Live started in 2024, and by 2025, they were already full throttle. The collective, spearheaded by Blak Dave and Proton and structurally backed by KVLT, approached nightlife with a simple philosophy: intentional, structured, and visually minimalist. This mindset was expressed through their signature monochrome aesthetic. Monochroma utilised the rhythmic familiarity of 3-Step to seamlessly convert normies into house enthusiasts, proving that the underground can grow without having to be clandestine, and without having to be diluted. This philosophy, coupled with the sonic direction of the Monochroma’s leaders, defined their 2025 programming and resulted in a year of cross-cultural convergence. 2025 on the Monochroma Live calendar culminated in the massive Dance Eko collaboration featuring Mörda, Blak Dave, JNR SA, Aniko, SoundsOfAce, and Earthsurfing, a finale that perfectly encapsulated Monochroma’s spirit.

In 2025, Sweat It Out solidified its standing as the raw, beating heart of the Nigerian underground, distinguishing itself by maintaining the gritty, industrial ethos of global rave culture. Under the sonic stewardship of resident headliner Sons of Ubuntu, the collective has kept the flame alive, curating sets that traverse the darker, more hypnotic corridors of Techno, Minimal Tech, and Acid House. The brand’s 2025 run reinforced its status as the scene's most vital safe space. Acknowledging the inherently queer roots of electronic dance music, Sweat It Out provided a rare, judgment-free sanctuary where gender expression and identity were not just tolerated but celebrated as essential to the technicolour vibrancy of the night. This commitment to inclusivity created a loyal following that prioritized the vibe over social hierarchy and/or buy-in. The year reached its apotheosis with "Sweat Therapy," a strategic year-end collaboration with Group Therapy. By closing 2025 with this unified front, Sweat It Out demonstrated that the underground remains undefeated, proving that a commitment to raw sound and radical safety is the strongest currency in the Lagos EDM scene.

While the major collectives dominated the headlines, the depth of the 2025 scene was defined by a constellation of parties that decentralised the culture and catered to specific communities. Leading this charge was Mainland House, which single-handedly dismantled the "Island-only" gatekeeping of Lagos nightlife. By planting the flag in different halls and production studios across the state, it offered a grittier, unpretentious alternative that tapped into the massive, underserved youth population of the Mainland, proving that the genre’s viability extended far beyond the elite coast. Simultaneously, Motion redefined the capital’s nightlife in Abuja. Far from being a shadow of Lagos, Motion carved out a distinct electronic identity, utilizing intimate spaces in the city’s capital to host rave experiences that currently sponsor FOMO and/or anticipation. In a bold expansion of the map, Red Light Fashion Room emerged as the avant-garde jewel of Ibadan, anchoring itself in the ancient city. A concept brought to life by Artpool Studios, Red Light Fashion Room created a unique hybrid that encouraged artistic expression via intentional grungy locations and the most original house rhythms, effectively modernizing the nightlife of the South-West beyond Lagos.

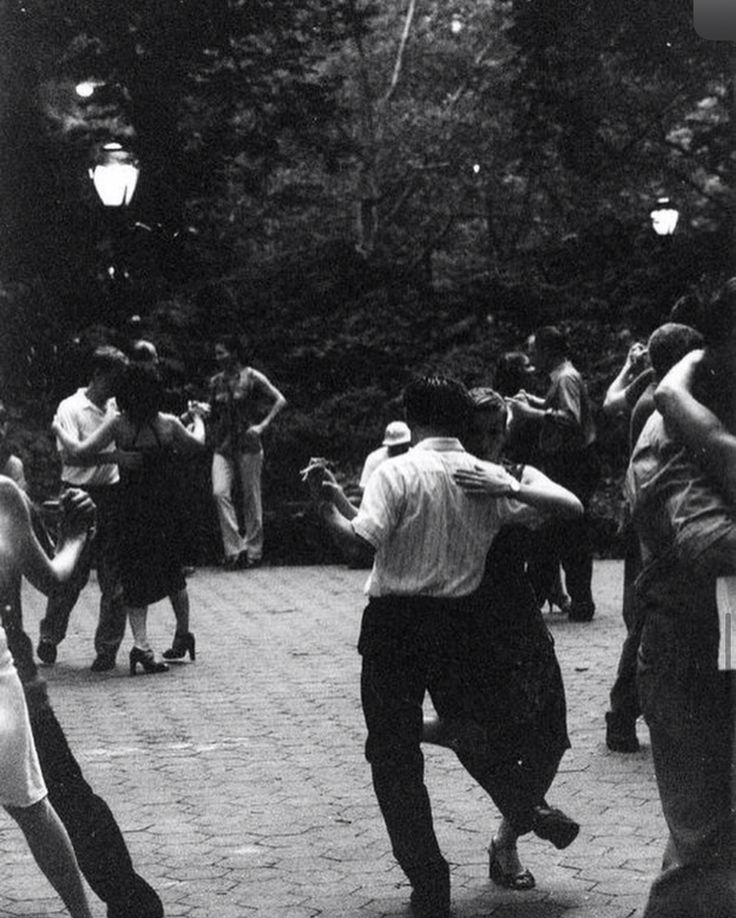

On the thematic front, the scene offered beautifully specific niches that prioritized "vibe" over sheer scale. Ilé Ijó (The House of Dance) stayed true to its name, stripping away the pretension of "cool" to focus purely on the kinetics of the dancefloor; it became the safe haven for those who wanted the soulful, spiritual connection of house music. Sunday Service enjoyed a highly successful year, with several editions becoming so popular they had to be shut down due to overcrowding. The event continued with its characteristic evening-to-midnight timing, with only a few unavoidable exceptions. Its relaxed, "sundowner" atmosphere proved vital, offering an accessible alternative for casual listeners who found the intense 3 AM warehouse scene intimidating. House Arrest, curated by the Naija House Mafia, had a year marked by a series of high-concept themed editions that demanded total commitment — not just from the crowd, but from the selectors themselves. Seeing the DJs spin while fully costumed on theme dissolved the barrier between the booth and the dancefloor, turning every edition into a cohesive, immersive performance rather than just a party. The Group Collective carved out a unique niche with their destination rave model, mastering the art of beachside escapism. Their editions, typically hosted at Tarkwa Bay, transform the rave into a 24-hour, overnight camping experience that demands total immersion. Their rapid ascent was cemented by the recent V4 edition, which saw them bringing in South African heavy-hitter Jashmir, signaling that this intimate, sand-and-sound community has graduated from a localized campout into a serious player.

In 2025, the "silo" mentality died. The most memorable events or editions were those where two or more heavyweights merged rosters and aesthetics.

Group Therapy x Boiler Room was the definitive event of the year. It validated the Lagos scene on a global level. It happened on the 26th of April with a lineup that featured a mix of established veterans from Lagos and abroad, including AMÉMÉ, Aniko, IMJ, and a Weareallchemicals b2b with Yosa. WurlD delivered a surprise performance, joining AMÉMÉ on stage during their set, adding to the already impressive lineup.

Green Light Fashion Room took the scene by surprise. Group Therapy teamed up with Red Light Fashion Room, a blooming EDM outfit operating out of Ibadan, to throw this memorable one. Many people remember it as one of the best EDM nights to ever happen in Ibadan yet. The lineup was nothing short of impressive either – starring Abiodun, Aniko, QueDJ, An.D, and Weareallchemicals – making the event nothing short of a masterclass in logistics.

Spotify Greasy Tunes served as the year's intersection of big-tech backing and underground culture, marking a sophisticated pivot for the scene. Partnering with the culinary hotspot Fired & Iced, this launch event kicked off a month-long residency that seamlessly blurred the lines between a culinary pop-up, a highly informative formal yap session, and a high-energy rave. Curated by Group Therapy, the opening night offered an experience that was anchored by South African 3-Step pioneer Thakzin, whose second stint in NIgeria was supported by a stellar roster including Aniko, WeAreAllChemicals, RVTDJ, and FaeM, setting a high bar for the fusion of food, culture, and electronic music.

Dance Eko distinguished itself as a massive, open-air festival that dedicated distinct days to Amapiano and House music. The House edition, executed in strategic collaboration with Monochroma, transformed the venue into a high-octane, open-air rave. The lineup was a formidable bridge between nations, featuring South African icons Mörda, Jnr SA, and the reunited Distruction Boyz (Goldmax & Que DJ). Locally, the decks were commanded by Blak Dave, Proton, Aniko, Abiodun, and Naija House Mafia.

Sweat Therapy was a masterclass in energy management. These movements combined the curated, deep selections of Group Therapy with the high-octane rave delivery of Sweat It Out. The result was a marathon-style party that happened on two floors of the multi-storey car park at the Odeya Centre, with each floor having its own sound – the type of rave you see only in a John Wick movie.

The Global Influx: International Players in the 234

The 2025 electronic calendar began with an intensity that signaled a new era for Lagos as a global rave destination. The influx started early in February when 3-Step pioneer Thakzin headlined a rainy edition of Monochroma. His performance was a defining moment that introduced hours of unreleased material and effectively cemented the 3-Step sound as one of the year's dominant rhythms. This momentum carried into April with a well curated event produced by M.E. Entertainment at the Royal Box Event Centre. Keinemusik’s Rampa brought the Cloud sound to Nigeria in a massive production that featured support from Aniko and Blak Dave. The night bridged the gap between underground electronic music and mainstream pop culture with surprise stage appearances by Burna Boy and Olamide. By May, the energy shifted towards Gqom as heavyweight Dlala Thukzin made his Lagos debut at the Livespot Entertainment Centre. It was the eighth edition and it is still quite fresh in the hearts of afrohouse lovers. His Group Therapy set is the most-watched house music set recorded in Nigeria and hosted on YouTube.

As the year progressed into the second half, promoters executed a strategic rollout of international talent that expanded the scene's geographic footprint. September saw a split of the legendary Gqom duo Distruction Boyz before their eventual reunion. Que DJ headlined the Group Therapy Ibadan edition on September 5, and just a week later on September 12, his partner Goldmax took over the Monochroma decks in Lagos. Thakzin returned for his second visit of the year on October 1 to headline the Spotify Greasy Tunes opening party. This specific appearance focused less on the rave aesthetic and more on a lifestyle approach that bridged dining culture with house and kicked off a month of talks, performances, and dinners at the same venue.

The final quarter of the year became a relentless parade of global superstars during the "Detty December" festivities. The surge began on November 7 when Gqom technician Funky QLA headlined the tenth edition of Group Therapy at Livespot and continued the collective's dominance in importing high-energy South African sounds. Deep House royalty Francis Mercier arrived on December 18 to headline Element House and brought his melodic house sound to the city. Desiree touched down shortly after for a highly anticipated set that showcased her eclectic Afro techno fusion. The year reached a nostalgic peak when Que DJ and Goldmax finally united on stage as Distruction Boyz at the Dance Eko festival in late December. They delivered a futuristic Gqom set that stood out as a major highlight. The year closed on an intimate note as Dlala Thukzin returned to headline Klub Aniko.

Beyond the headline shows, several other key figures deepened the scene's texture through niche and endurance events. Jashmir headlined The Group Collective’s V4 beachside camping rave at Tarkwa Bay and tested the endurance of the 24-hour party crowd. Dankie Boi became a recurring fixture who played pivotal sets for both the Group Therapy Abuja expansion and Monochroma in Lagos. Meanwhile, Skeedoh, Abiodun, and Ogor ensured that Ilé Ijó continued to educate the scene on the fringes of African electronic music by maintaining a robust relationship with the East African underground. Ile Ijo championed the fast-paced Tanzanian Singeli sound pioneered by acts like Jay Mitta and ensured the Nigerian scene remained connected to the continent's rawest and most traditional electronic roots.

The Ecosystem: Platforms and Partners

The sustainability of the 2025 boom was underpinned by a rapidly professionalizing support system that ensured the culture was not just experienced, but structurally sound and amplified. Central to this operational evolution was Our House. Far more than just a promotional platform, Our House functioned as the scene’s logistical backbone. Under the stewardship of key figure Becky Ochulo, the agency provided the essential human resources, operational strategy, and on-ground management that allowed complex rave productions to run smoothly. Furthermore, they professionalized the talent pipeline, offering booking and management services that finally gave Nigerian electronic artists the representation needed to negotiate with global stakeholders.

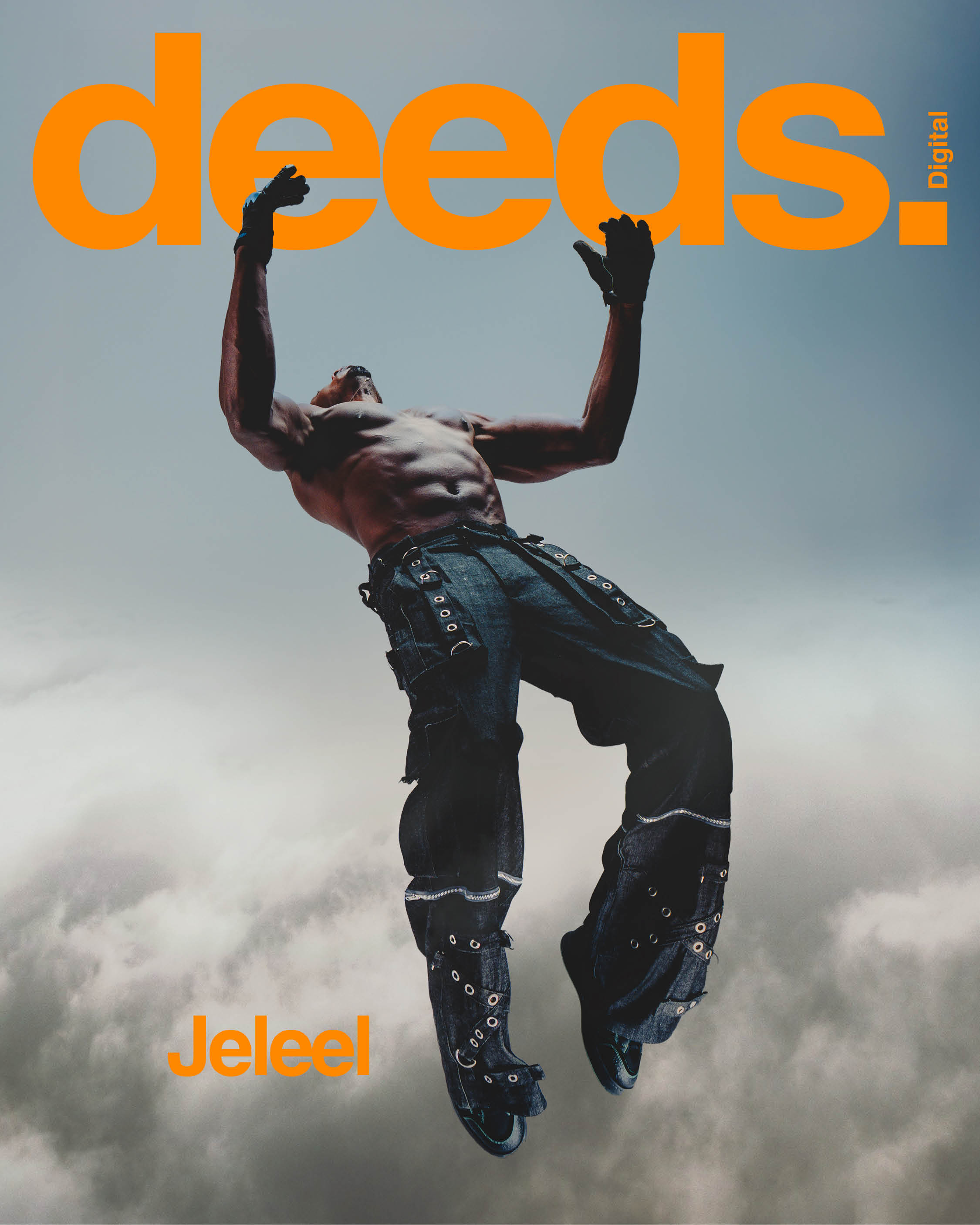

On the media front, platforms like Nocturne Music and Oroko Radio acted as the scene’s digital nervous system. Oroko Radio, in particular, served as the definitive archive, broadcasting underground sets to a global audience and ensuring that the energy of a Lagos warehouse was felt by everyone who could tune in. Visually, the aesthetic of the "Nigerian Raver" was codified by documentarians like Catch The Gigs, Exponential Vibes, and Genuine Ravers. These platforms provided the scene’s visual dialect, capturing the fashion, the sweat, and the darkness in ways that made the culture instantly recognisable on social media feeds worldwide. Deeds Mag established itself as an indispensable lifestyle collaborator, effectively linking digital media presence with tangible cultural output. Beyond offering comprehensive media coverage for major events, such as the widely successful Nitefreak show, they became crucial in shaping the visual culture of the scene's growth. Their partnership extended to serving as the aesthetic designers, including the creation and production of exclusive merchandise for the GT on Tour series, guaranteeing that Group Therapy's visual identity remained high-end and consistent as the rave expanded to cities outside Lagos.

This heightened structural integrity inevitably attracted capital. Giants like Smirnoff and Coca-Cola became ubiquitous, providing support required to scale these events. However, the soul of the ecosystem remained with QuackTails. Unlike the multinational giants, QuackTails has been there for quite some time – almost as early as the very beginning – providing a sense of authenticity and familial support, proving that the scene still valued community partnership over mere commercial sponsorship.

Looking forward, 2025 marks the maturity of Nigerian electronic music into a self-sustaining industry with a distinct global footprint. The spread of the sound is being driven by the diaspora and digital platforms, successfully integrating Nigeria into the global electronic tour circuit. The economic implications are profound, creating thousands of new jobs in event production, sound engineering, and creative direction. Perhaps most importantly, it has granted producers a new form of creative freedom; they are now empowered to engineer anthems for the dancefloor, designed for physical release rather than airplay, proving that the genre has found its own independent commercial lane.

Yet, this renaissance is being built on fragile ground, and the challenges facing the scene are as potent as the music itself. The infrastructure gap remains the most glaring hurdle, with a desperate need for dedicated, sound-treated locations to replace the makeshift venues currently in use. This lack of infrastructure complicates safety; as raves push deep into the early morning hours, protecting attendees during transit and navigating the complexities of local policing remains a source of constant anxiety for organizers. Furthermore, the economics of the scene are still precarious. Despite the corporate logos, Nigerian EDM is still in its infancy, meaning that much of the current activity is a financial labor of love driven by passion rather than profit. Finally, the scene faces a significant cultural friction: the struggle for acceptance in a conservative society. Given the genre’s inherent roots in queer culture, there is an ongoing tension regarding perception and safety, forcing the community to navigate the delicate balance between radical inclusion inside the rave and the conservative realities outside its walls.

In 2025, Nigerian house music found its voice. It was a rhythmic conversation between the pulse of Lagos and the sweat of its wide-eyed, vivacious youth. We are witnessing a scene growing in leaps and bounds, a reality validated not just when our institutions plant their flags on foreign soil — manifested this year in the successful exports of Group Therapy Accra and Group Therapy London — but in the undeniable global demand for our talent. The sound is now a veritable currency, evidenced by Blak Dave securing bookings around the world and Aniko’s monumental inclusion on the ADE lineup. At the same time, she and WeAreAllChemicals have become staples on major festival stages across Africa. We owe this current expansion to years of grassroots effort. For example, Dayo’s work with The Group Collective’s V4 effectively redefined the nexus of lifestyle, local camping, and EDM. At the same time, Lazio has solidified his reputation as the premier sound engineer for the electronic community and, effectively, the silent partner behind every major sonic activation. The movement has become truly boundless, stretching far beyond Lagos to unlikely frontiers like Calabar, where Kuffy Eyo’s Nocturna is pioneering a new consciousness in Nigeria’s geopolitical South-South. Through the support of these symbiotic microcosms, the Nigerian rave has graduated from a local secret to a viable cultural product. 2025 rolled into 2026 as the Sunday Service crowd crossed over at Lighthouse Bar and Grill, and one thing was clear: everyone is eager to see what 2026 holds for tinko-tinko music.

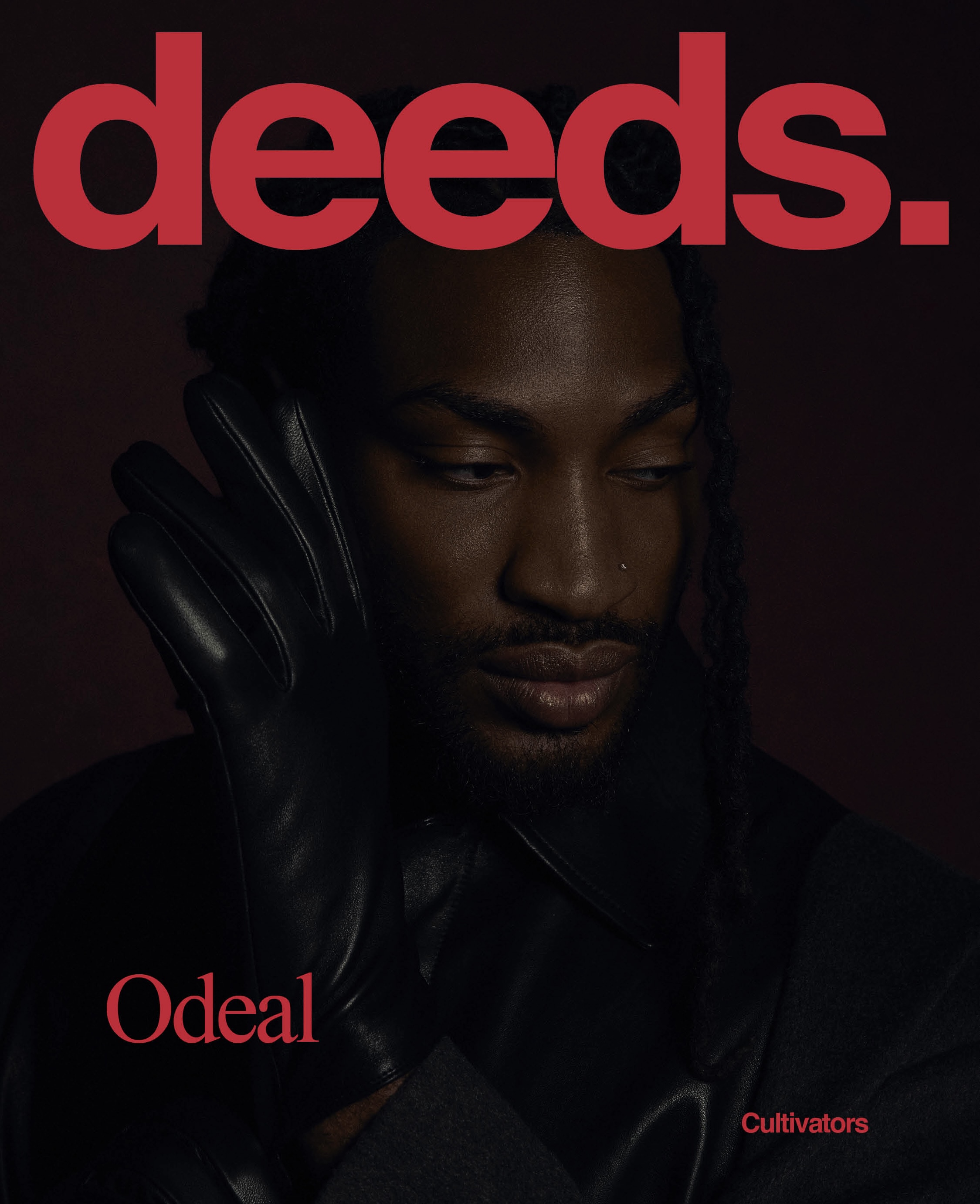

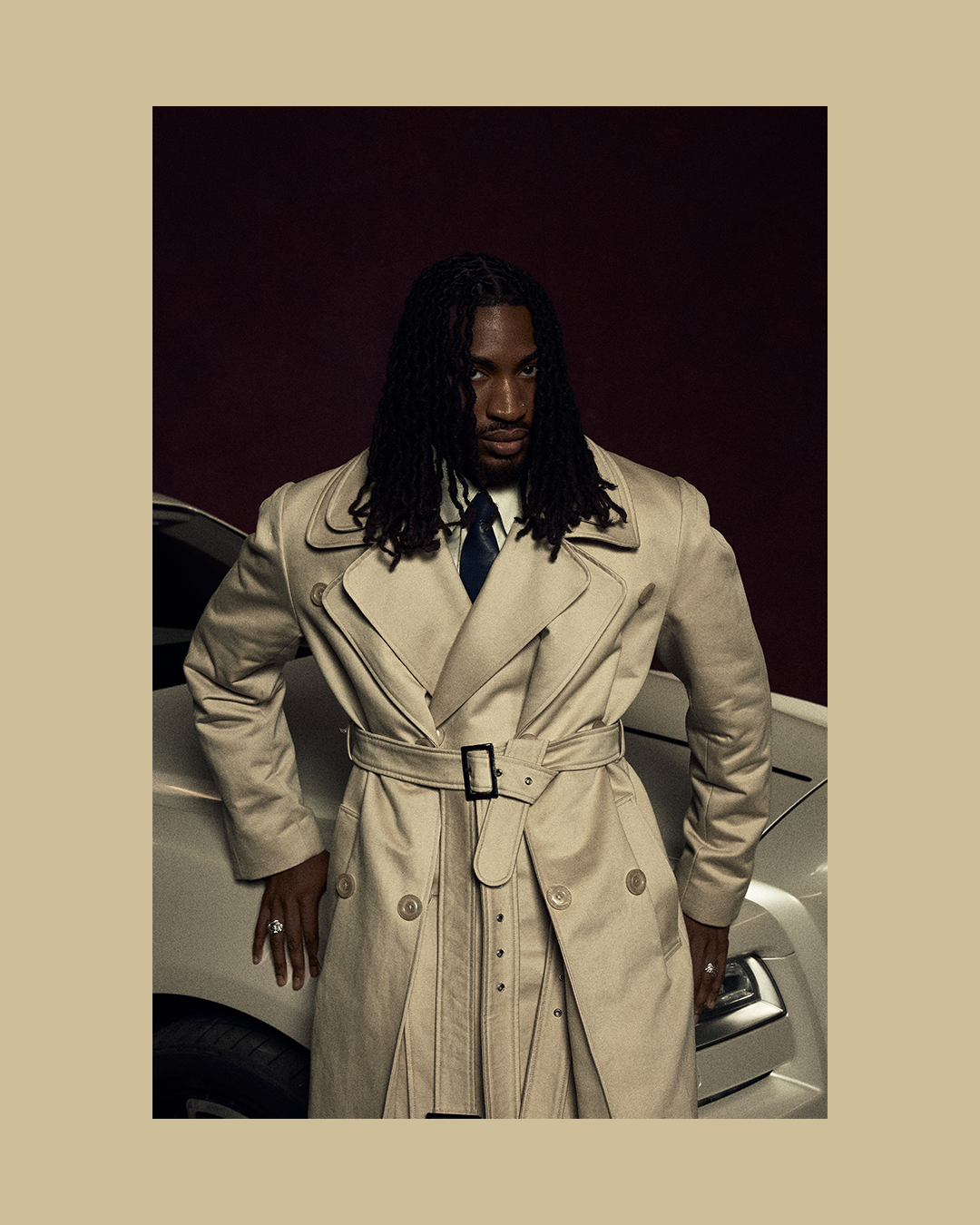

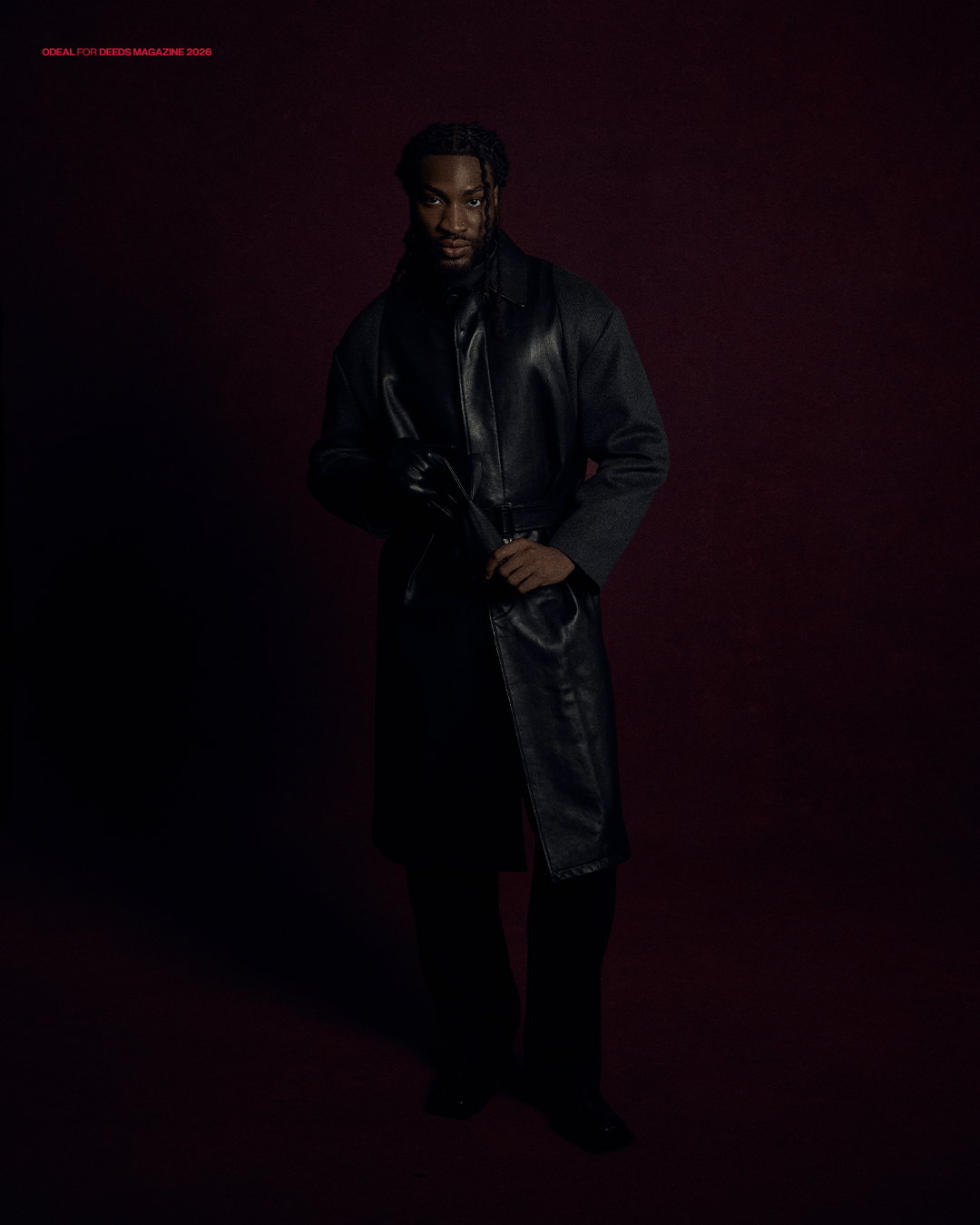

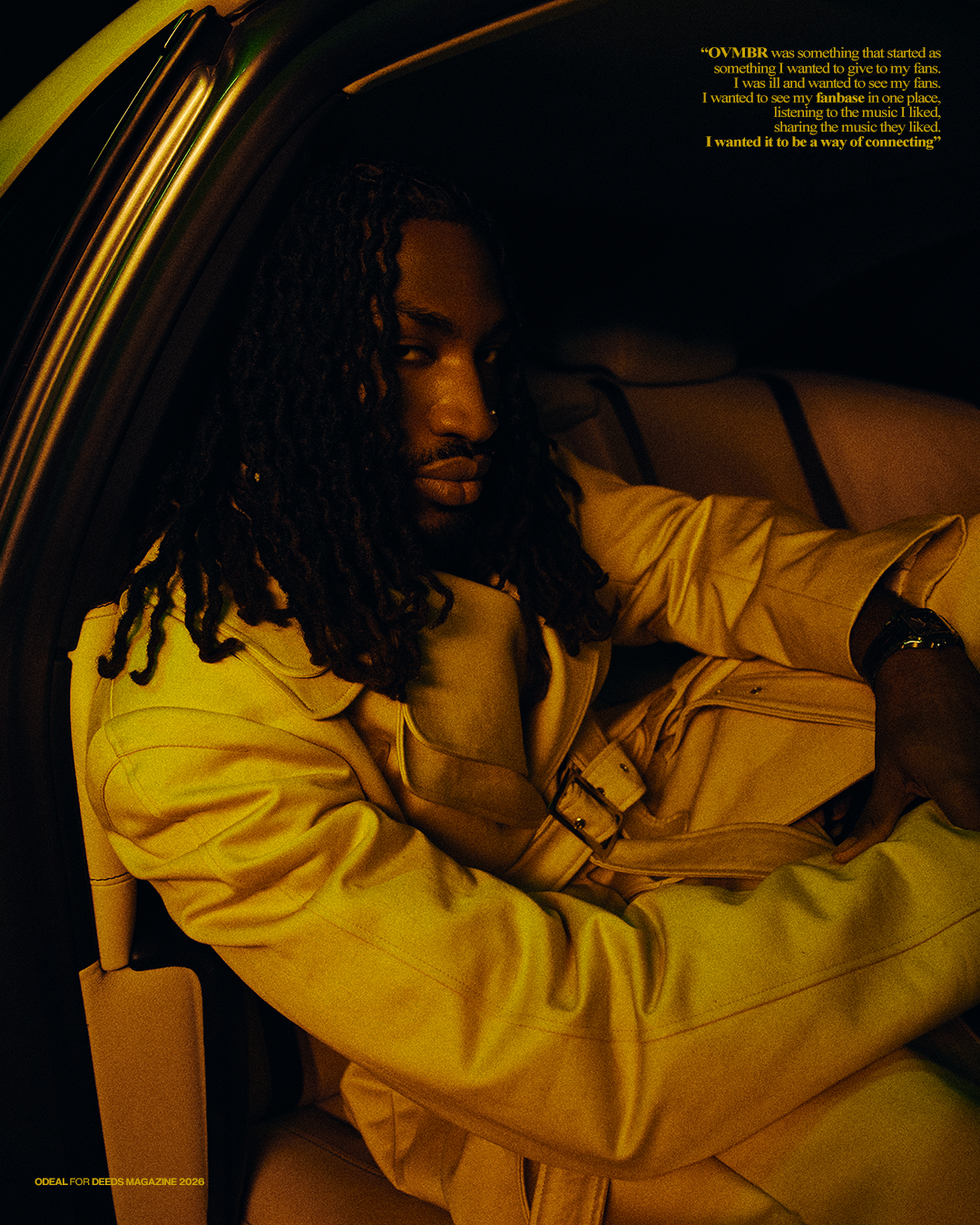

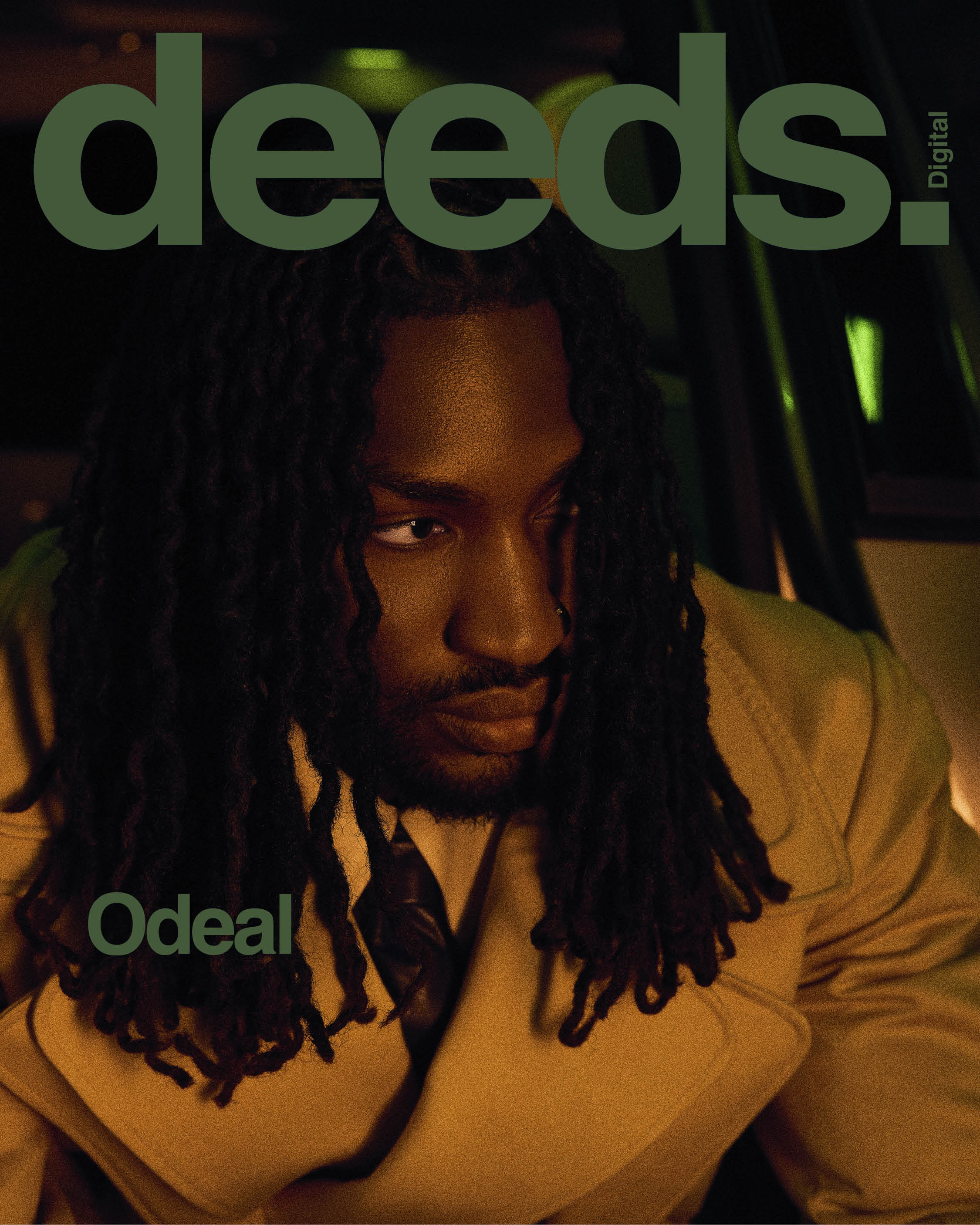

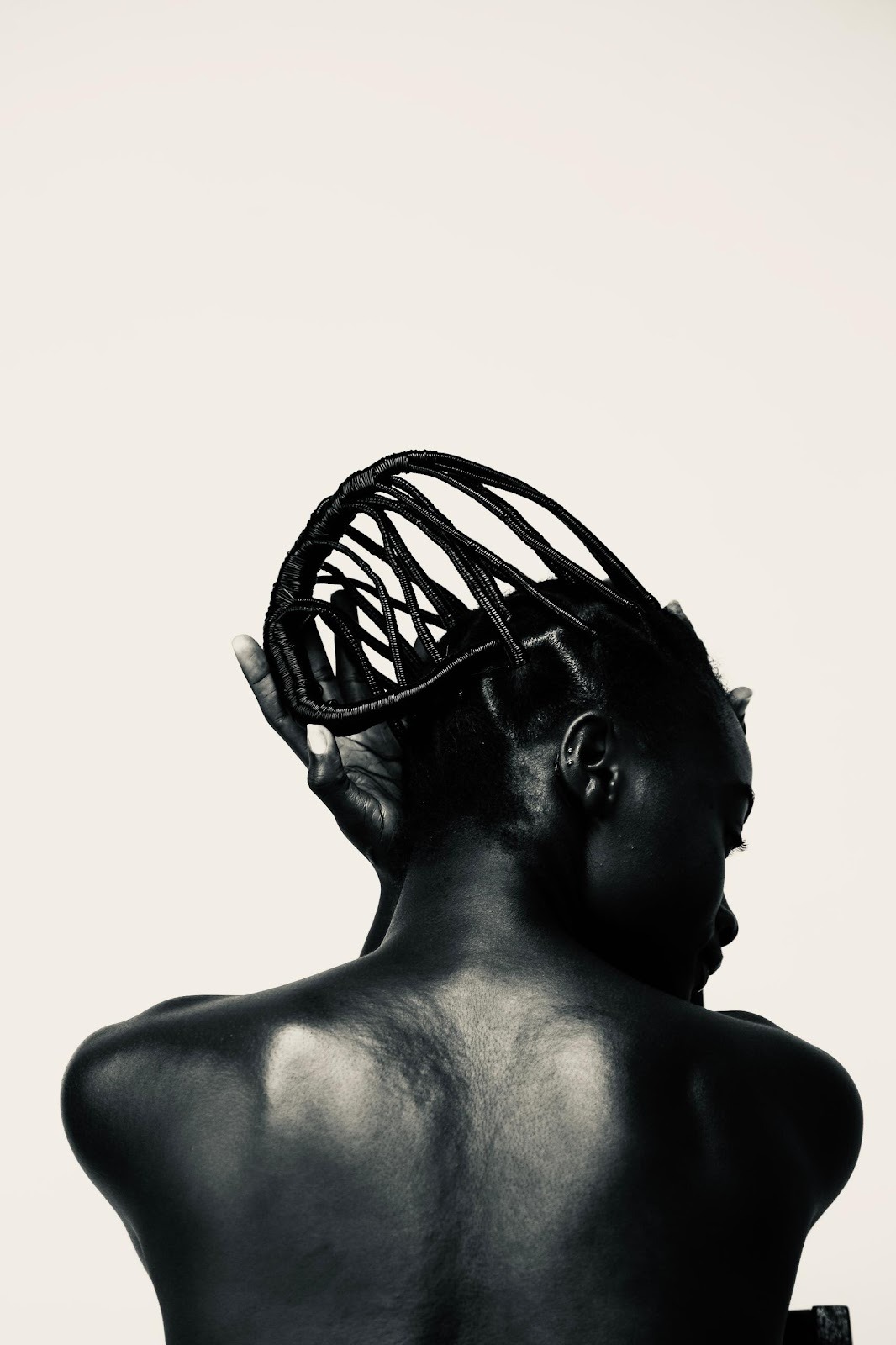

When Odeal arrives on set, it is a cold day in November in London. Despite the overcast weather, there is an energy throughout the day that brings excitement in the air. As someone who has had a fairly active year, he has a calmness that makes the 6-hour day run smoothly and painlessly. With various movements underway and people doing what needs to be done, he maintains an aura of readiness to do whatever is required. As we move through the day, he keeps the energy and vibe up until we wrap up for the dark evenings of a November night, showing his gratitude and appreciation for everyone on the team. Our conversation, which takes place a few weeks after the shoot, only echoes that vibe as we speak over Zoom. Having previously interviewed him around the release of his 2023 EP Thoughts I Never Said, this Odeal is on the move now, currently in Dubai. Yet as the conversations unfold, the essence of the artist I spoke to two years ago remains the same, even though he is in a different place in his life.

With all the changes since our first meeting, there is a lot to unpack. As he has grown personally and artistically, his confidence and elevation have come through across the board. He still maintains the same level of vulnerability, which has always come through in his music. Yet from the time between Thoughts I Never Said, Sunday’s At Zuri, Lustropolis and the two projects he released in the past year it feels like he has continuously grown deeper within himself and his vulnerabilities he continues to display in a way that has brought him to his current place where I once again meet him on his journey.

Since his debut in 2017, his musical style has evolved, cementing him as one of the freshest voices in the music landscape. With all that he has achieved throughout the course of his career so far, Odeal is an artist who is at the centre of the current R&B landscape a the moment. The likes of Lustropolois and his most recent works, The Summer That Saved Me and The Fall That Saved Us, have showcased the richness of his storytelling and his ability to do so through strong production, smooth melodies, and compelling lyrical content. It is his openness and vulnerabilities that have always come across so smoothly, really showcasing him as an artist who continues to put his own stamp on the genre.

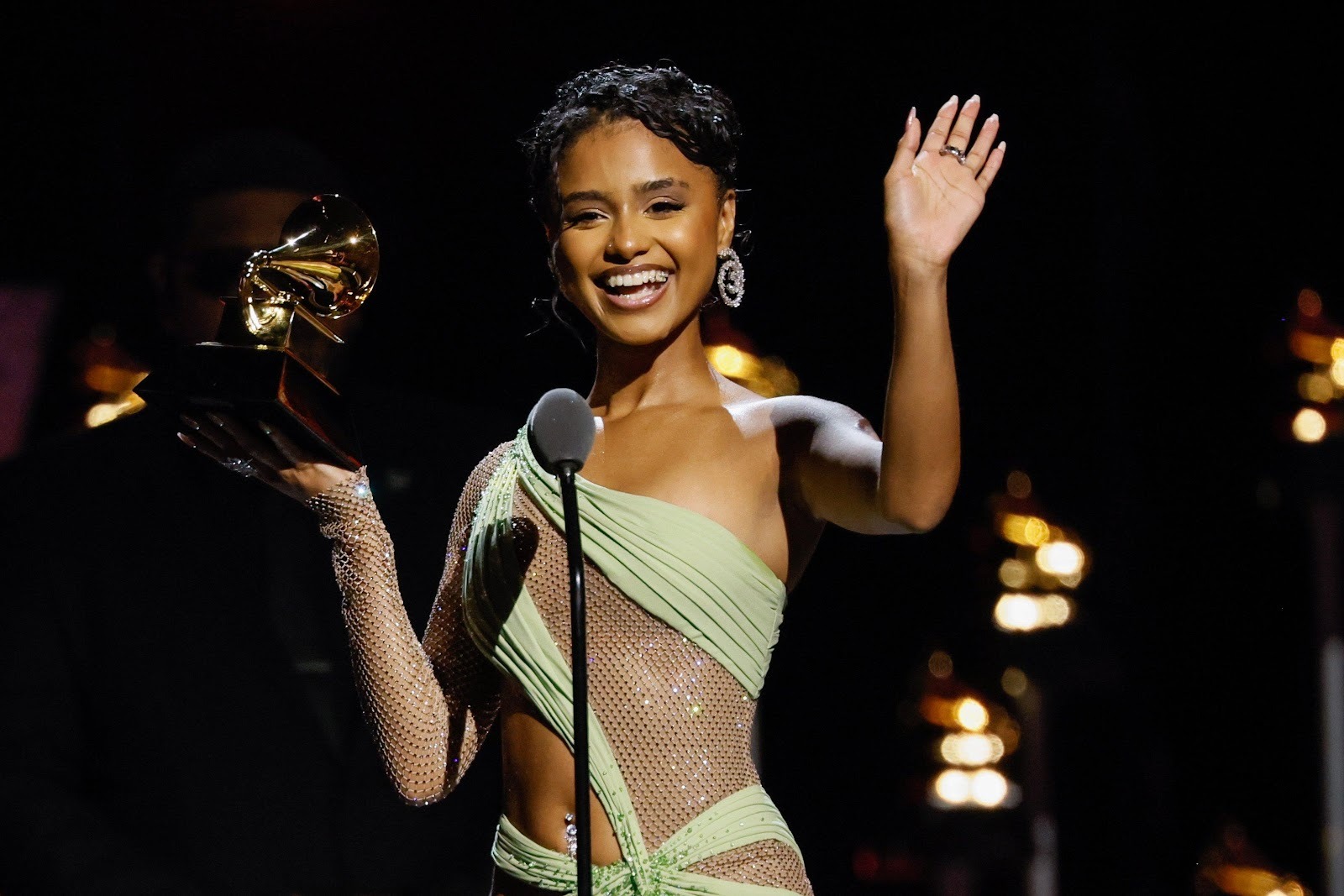

We caught Odeal as he wrapped up a busy year. Just before closing out the year in South Africa and Nigeria, he took the time to come through and deliver a shoot that reflects his position as a cultivator in the R&B landscape. His year began with two Mobo Awards wins and was filled with shows that took him around the world, a Tiny Desk debut, and the release of two EPs. There is no doubt that all these experiences have been the result of years in the making.“For many people, it feels like it happened quickly, but I've been doing this for a long time. There is so much I've got to learn, and I've got so much to give,” Odeal shares with me as we discuss his global breakthrough and what the last few years have felt like.

Whilst on set, The Fall That Saved Us plays as one of the soundtracks as we shoot the final setup of the day. “Reason”, which features LA singer and producer Elijah Fox, opens the album and introduces a sound that is already vastly different from his previous offering. The second of two EPs brings in a darker, moodier tone that runs throughout. “The Fall That Saved Us was more like summer's afterglow. What are the things that still linger in your mind? What are the things that have been left behind, that remain in the back of your head? That's really what it was for me once everything's done, once the party's over. How do you feel? That's really what I wanted to explore on this project.” He shares his thoughts on the tone of this EP compared with its summer counterpart, released earlier this year. Whilst it feels like we have left the emotions of summer, this particular body of work echoes 2024’s Lustropolis in tone and feels like a distant echo of that body of work. In the Lustropolis state of mind, we have all been too familiar with The Fall That Saved Us; it feels like something from that world.

In comparison, The Summer That Saved Me departs from that mindset. Starting with “Miami”, which brings one into a completely different reality, readies an alternative reality. This was something Odeal felt necessary following the tone set from Lustropolis “The Summer That Saved Me was a project that I wanted for the summer, for people to leave that Lustropolis place and just celebrate, enjoy themselves, be selfish. That was the soundscape for me, that's what created that.”

The two projects perfectly show the extent of his creativity, yet they tie together to explore the range of emotions and experiences he brings to his music. “I make music for myself a lot of the time. I'm always making music I want to listen to, and I'll keep listening to it throughout the seasons I’m in,” he says about the process that informs his ability to create music that feels so relatable and goes deeper than just good melodies and rhythms. “Some songs resonate on some days; some don't on others. As I live my life, different feelings pass; some do not pertain to my current situation. And other songs become the soundtrack to my day.” His creative process has always been informed by whatever situation he find himself in and this is something he has continuously been able to pour into his music whatever the topic, whatever the feeling created a body of work that is rooted in a deep truth and authenticity that can lacking in the musical landscape of today and is just one thing that has been able to set him apart as an artist.

Odeal’s creativity has always extended beyond musical releases. As a cultivator, he has built more than just a fanbase around his music; he has also created a strong community that is strong and has grown beyond artist and fan. The creation of OVMBR, which began as a celebration reminder after he faced an illness, has become a movement. As a collective of artists and creatives, it has hosted community-led events and parties over the years at various locations. It is a space that fosters a community of fans and creatives and celebrates individuality, resilience, and diverse experiences that strengthen the collective. The celebration and growth of his work have always been part of Odeals' creative vision and have developed alongside his artistic career. In its seventh year, its impact and significance have been evident throughout the year. “OVMBR was something that started as something I wanted to give to my fans. I was ill and wanted to see my fans. I wanted to see my fanbase in one place, listening to the music I liked, sharing the music they liked. I wanted to be a way of connecting,” he shares about its conception, which became another pillar that has been marked by the love and shared community that he has been able to foster throughout the years.

Travel has always been a big part of Odeal’s life, from the years he spent growing up between Germany, Spain, the UK, and Nigeria. It is no wonder that when you listen to music, you feel a sense of unity. Whilst a core of R&B infuses his melodies and lyrical tones, beyond that, soundscapes from various global destinations are also evident. This ability to infuse, blend, and bring together sounds from around the world while maintaining his signature storytelling has allowed Odeal to flourish.

Not only has it shaped his life and experiences, but it has also been a major part of his creative process and of how his music relates to people around the world.I am interested in how he continues to grow and develop his sound globally as he reaches new destinations and incorporates diverse sounds into his music. “The way life has opened doors to creatives around the world, allowing me to collaborate with them now, is a blessing. I can go to different places and find different vibes, inspiration, and access information on a personal level. It definitely fuels the creative.” He says that it is part of his process. However, on the other hand, when it comes to creating, he always has a fan base and people he can reach all over the world. “Having supporters in different places around the world makes the music more relatable. I know that whatever I make will resonate in a certain place.” He shares about what it feels like to go around the world and see how different people respond to his music. “If I make this song, it's going to resonate in this city or this place. I have people all around the world who are ready to listen. They're literally everywhere, and just knowing that you have a wide fan base means I can go anywhere and become like a citizen of the world,” which is something he has been able to experience firsthand in relation to his music career. As he prepares to embark on his upcoming tour, The Shows That Saved Us, which will take him across the UK and Europe before opening for Summer Walker on her Still Finally Over It Arena World tour.

Odeal is no doubt in a special time in his career. With many miles to go and many avenues still to reach, there is a lot more to him to explore and delve into when it comes to the depth of his creativity. With the release of his Apartment Life set, we saw him tapping into a different part of himself as a DJ, which is something I must address, having heard his set not knowing it was him and which I 100% recommend. “In everything I do, I need to respect the people who came before me and those who are doing it very well. When it comes to DJing, I don't want to do it just because I’m an artist. I actually want to pay homage to the people who really do this properly,” he says of what fostered his interest in the format and how he has actually been building the skill within himself. When pressed about whether we will see more of this newfound skill and talent on display, there is definitely more on the horizon. “People will definitely be seeing more of that, infused with my production, not just playing other people's records or introducing other people to records, but also things like unreleased music I've produced. That's going to be some stuff I do.”

There is an excitement about everything that is on the horizon for Odeal, and now he really feels like his moment to take everything in and go with it. Beyond what we discussed, he has a limitless mindset about what he aspires to do and achieve in his career. Having reached him at this point in his career, we were able to capture a special moment. Seeing where he is now from the time of our last conversation, I wonder where I will next find him on his journey.

Our Favourite New Mashups So Far

If one were to best explain the surge of R&B music in recent years, this phenomena could be traced back to the current state of rap. Although the two genres were forged from different roots, historically speaking, these separate sonic worlds always intertwined. And as the once-dominant gangsta appeal that is prominent in rap is slowly dismantling and fading away, it leaves room for softer sounds and love anthems to flood down our headphones once again. It is all in the air wherever you look at; love season has finally returned and this is our favourite picks that have dropped this year so far.

Raindance - Dave & Tems

Is it just us or is it getting hot in here? Perhaps the duo that instantly drew us in this year is none other than Nigerian sweetheart Tems and London rapper Dave, whose No.1 chart-topping track ‘Raindance’ has a special replay button on our playlists. While the collaboration was first unveiled in November along with Dave’s latest album, it was the Lagos-shot music video released in January that really won us over and sealed the deal. It’s a dance anthem, it’s a love anthem, it is everything in between–open to interpretation by music listeners and wandering ears alike. Everyone on the internet is dancing to this song, and it seems like rumours swirling around the pair have us believing in love again.

STAY HERE 4 LIFE - A$AP Rocky Feat. Brent Faiyaz

We can all agree that almost 10 years of absence by Harlem’s finest A$AP Rocky was worth every second of the wait. And perhaps he might have accidentally ignited a comeback from R&B singer Brent Faiyaz as well, serving us everything our hearts could desire on a silver platter with ‘STAY HERE 4 LIFE.’ Now we can see why Rocky, aside from father duties, took his sweet time; he was aiming for a swaggy track coupled with harmonizing vocals that babies can be made to.

Nights In The Sun - Odeal Feat. Wizkid

There’s nothing like returning back overseas, on the plane reminiscing about detty December in Lagos, while ‘Nights In The Sun’ by Afro-fusion artist Odeal featuring Nigerian’s starboy Wizkid is playing in the background. Of course, we would know nothing about such; however, this is as far as where the track takes us. And through the carefully-crafted visuals that dropped in January, it only felt as though the feeling was amplified. At this point, Odeal has no misses in his reinvention through R&B eclectic takes.

wyd - Plaqueboymax & Bryson Tiller

Last but not least, on a surprising release by Streamer, producer and now emerging rapper Plaqueboymax, the young online personality really shook us to the core with Bryson Tiller on ‘wyd.’ While he is still trying to balance life in pursuit of a newly-found passion, in his first single of the year, Plaqueboymax offers a vulnerable side to him that he had not yet displayed, both online and sonically. The lyrics are raw, the music video featuring rumoured new fling Keke Palmer is steamy, and Bryson has the ability to create the perfect atmosphere of melodies into the ensemble.

Clarence Ruth is not interested in art that stays behind glass. A multidisciplinary force, spanning fashion collaborations with Mercedes-Benz and Tommy Hilfiger to fine art, Ruth’s latest exhibition at Ki Smith Gallery reimagines the 135-year legacy of the Carrom Company. By transforming vintage gameboards into canvases, he explores the intersection of heritage, communal joy, and the necessity of thinking outside the box.

You’ve mentioned your upbringing in a large household influenced this project. How did those early years shape your view of play as art?

I grew up in a deeply structured, faith-centered household where art became my sanctuary of unstructured thought. We didn’t always have the latest technology, so gameboards like chess and dominoes were how we bonded, they brought us into communion away from screens. In my community, these boards are where elders pass down lessons of strategy and patience. Using them as canvases felt organic, because our leisure and our joy are worthy of being celebrated as legitimate art.

When you look at a vintage 135-year-old Carrom board, do you feel restricted by its history?

I perceive both its history and its latent possibility. I have deep reverence for the 135 years of heritage and the generations of hands that touched these boards before mine. But I also see an opportunity to layer a contemporary narrative onto that foundation. These boards have already lived meaningful lives, now they get to carry new meanings and ignite different conversations.

What is the essential vibe in your studio to get into the Clarence Ruth headspace?

It starts with prayer. to center me and connect me to my purpose. Once I’m immersed, music is the force that carries me forward. Artists like D’Angelo, Keyon Harrold, and Pharoahe Monch create the sonic landscape. Their sophistication and improvisational qualities remind me to stay fluid and responsive to what the work is asking for.

Walking into Ki Smith Gallery, you realise you aren’t just looking at pieces, you’re looking at a reclamation of imaginative freedom. The genius of Clarence Ruth is rooted in his intentionality.

By refusing to stick to a single theme, Ruth ensures that people from all walks of life can connect with at least one piece. While the styles vary from technical precision to soulful sketches, the lack of a uniform aesthetic is the point, it represents our diverse world coming together in one space. If we can all come together on common ground, represented here by the Carrom board, it proves we have much more in common than we think. Ruth is deliberate with these differences. He doesn’t see them as a negative; he uses them to create what he calls a “sustained chaos” that gets people talking and interacting.

The exhibition also features Knock Hockey boards, which provide a beautiful, framed-canvas feel. Ruth was adamant that these boards retain their playability, they are meant to be touched and felt. In a world where the youth are glued to screens, he is using these boards to encourage us to look at one another and enjoy physical presence.

Clarence Ruth is a true originator. Whether he is designing fashion or painting his “Oreo” series to discuss identity, his work is about expanding beyond narrow categories. This exhibition is a blueprint for the future of creative innovation. As I left the gallery, I was reminded that art is most powerful when it stops being a distant object and starts being a lived experience.

“The artist cannot and must not take anything for granted, but must drive to the very heart of every answer and expose the question the answer hides. I am what time, circumstance, history, have made of me, certainly, but I am also, much more than that. So are we all.” — James Baldwin

Clarence Ruth proves that while the rules of the game are set by the past, the way we choose to play is what creates the future.

All photographs byJelani Warner.

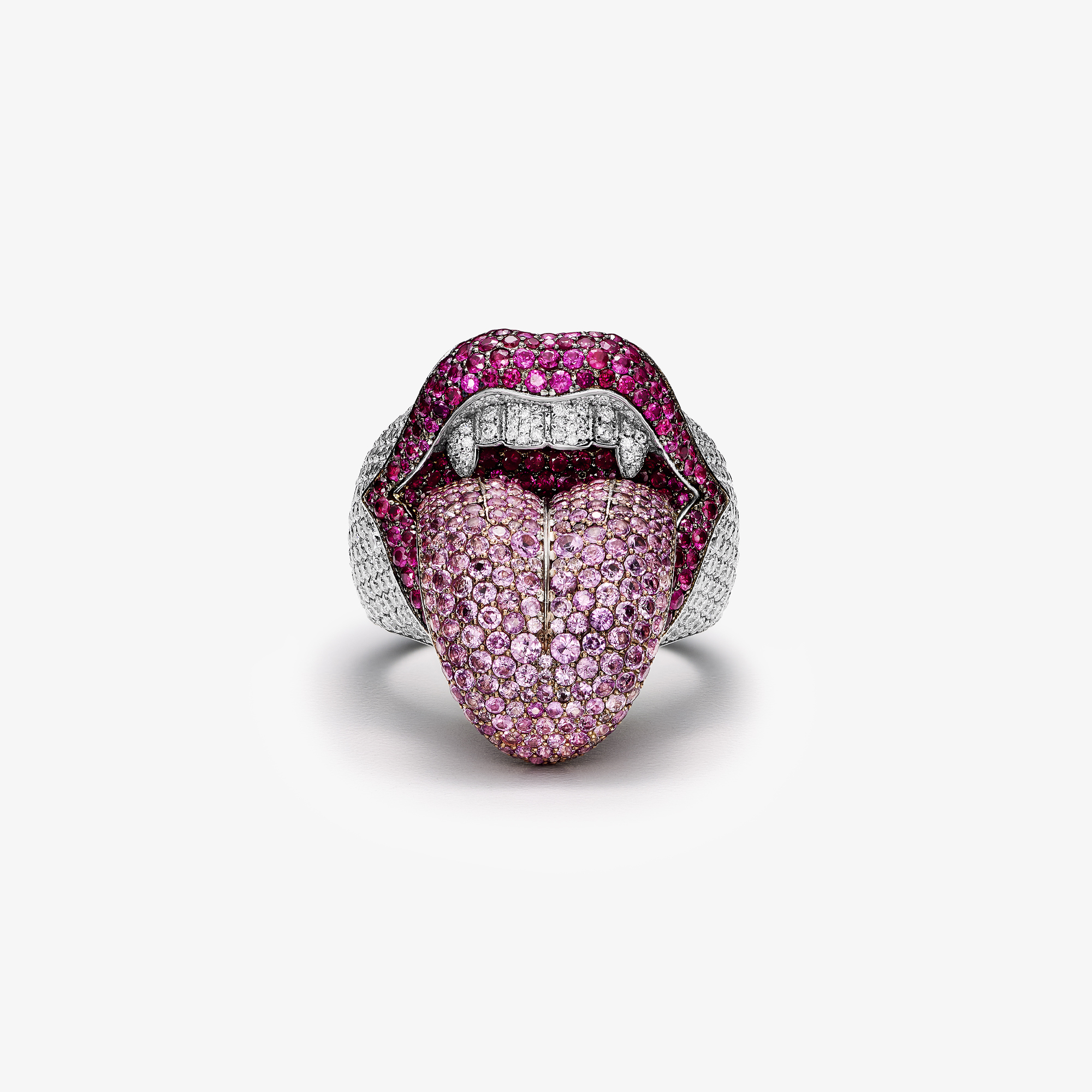

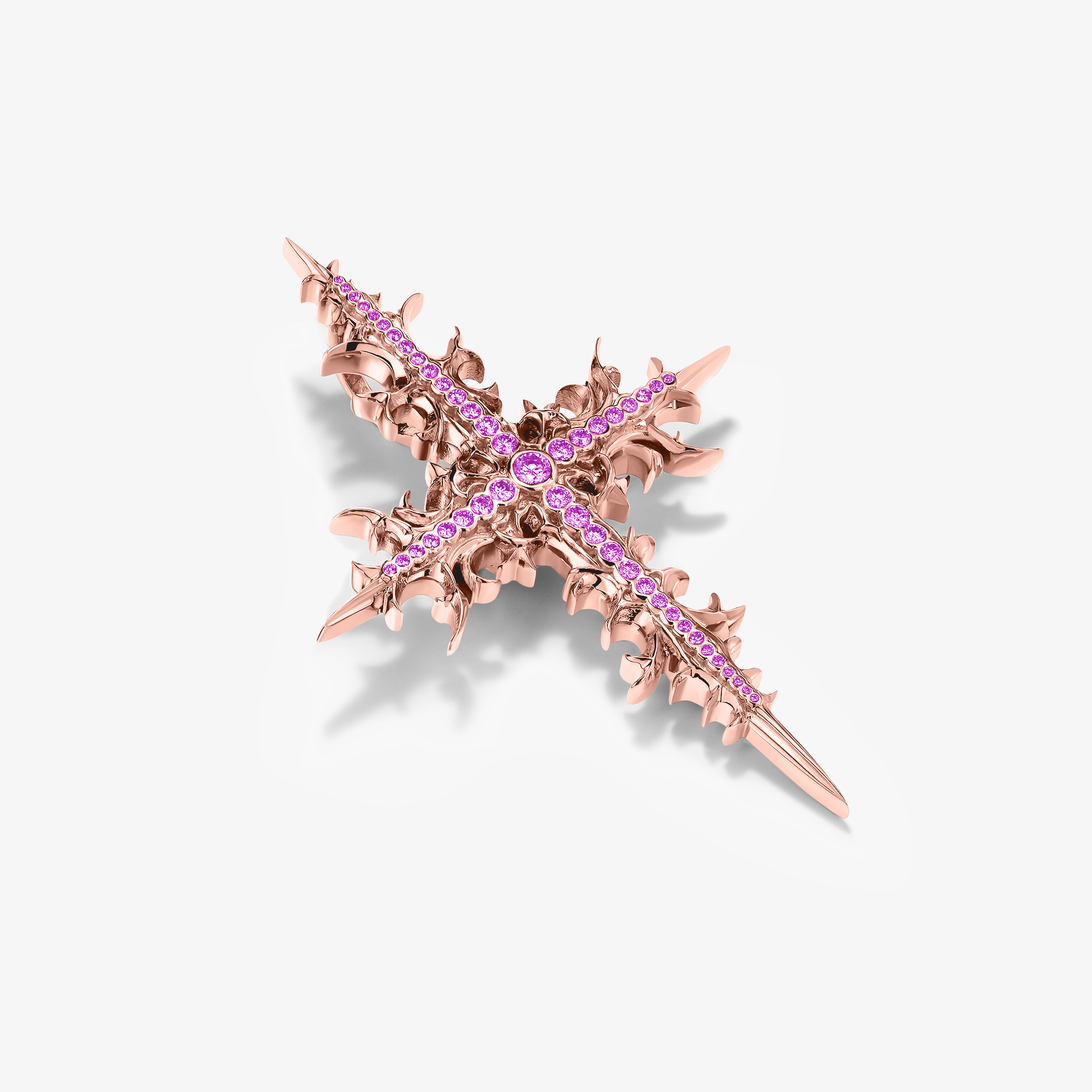

Deep within the architectural pulse of New York, where the echoes of European Gothic design meet a relentless "NEO" philosophy, jewelry is being redefined. In this landscape, Alex Moss does not merely create accessories; he constructs modern relics, physical manifestations of personal history, rendered in gold and stone. While many brands default to the safe and conventional, Moss operates through a non-conventional lens, approaching jewelry as architectural structures rather than simple decorations.

When we go with what we love, a gift becomes deeply impactful. Alex Moss acts as a translator for his clients’ personal narratives, building each piece as a meticulous exercise in visual language designed to communicate the wearer’s identity. That specificity separates his work from the world of mass produced luxury and has drawn cultural icons such as Drake, A$AP Rocky, Tyler, the Creator, and Playboi Carti into his orbit. For these individuals, a piece from Moss is not just a purchase; it is a collaboration born of a specific, shared vision. By building symbols rather than just setting stones, Moss ensures that the jewelry feels organic, true, and purposeful.

To join this circle of owners is to shift one’s perspective on value, and that shift is what makes Alex Moss a compelling choice for Valentine’s Day. Moss himself frames his work as a long-term investment, drawing a distinction between what he calls the “Bentley” of craftsmanship and the “Honda” view of standard retail. These are heirlooms intended to be passed down through generations, not accessories that fade with the season. The technical excellence is uncompromised: gold foundations, secure settings, high-grade diamonds with VS+ clarity and D-F color for maximum brilliance, and micro-pavé techniques meticulously applied to capture light at every angle.

Taking inspiration from the St. Marks aesthetic and the study of European Gothic style, Moss creates work that carries both weight and edge, pieces that feel as enduring as the forms they reference. His “NEO” philosophy draws on the tension between ruins and futurism, visible in bold, sculptural forms like the Nirvana Cross. Whether through the sharp lines of the Wild Rose or the deliberate use of Light Pink Sapphires to soften an otherwise heavy silhouette, his creations tell a story that goes beyond ornamentation.

Ultimately, an Alex Moss piece moves beyond the tired clichés and familiar gestures of Valentine’s Day gift-giving. When you choose a gift of this caliber, you are not purchasing an accessory; you are securing a legacy-based investment. Much like a profound love, the value of an Alex Moss creation is designed to increase over time, mirroring the depth of the bond it represents.

From the 1950s to today, Black models have shaped how fashion looks, and sit at the centre of fashion’s evolution, even as the industry struggles to move in step. Since the mid-20th century, they have shaped its imagery, expanded its imagination, and redrawn the industries boundaries. Their influence is embedded in fashion’s visual archive — visible everywhere, but frequently positioned at its margins. Across decades of shifting aesthetics and unfinished conversations about inclusion, Black models have continued to move the industry forward, often with recognition lagged behind their labour.

With the rise of fashion media in the 1950s to today’s hypervisible landscape, modelling has operated within narrow definitions of beauty and belonging. Agencies, designers, and editors repeatedly privileged a singular body type and skin tone, turning exclusion into structure rather than exception. Within these limits, Black models carved out space. Through presence, precision and refusal, they expanded what fashion permitted itself to see. Black models have carried fashion forward visually even as the industry resists moving with them structurally. Their labour has widened the language of beauty, challenged the geography of luxury, and forced the industry into conversations it routinely tried to defer.

Naomi Campbell and Iman reshaped the global runway, scaling Black visibility at a time when access remained tightly controlled. Beverly Johnson altered the politics of fashion media after becoming the first Black woman to appear on the cover of American Vogue. Others shifted the industry no less decisively — from Mounia becoming Yves Saint Laurent’s first Black muse to Alton Mason walking for Chanel, rewriting the codes of luxury from within.

These moments established foundations. They altered the terrain, allowing younger generations — the faces now defining contemporary fashion — to arrive into a landscape already changed by those who came before them.Today, Black models move through fashion with a different kind of visibility. Their faces anchor campaigns, open shows, and shape seasons in real time, circulating endlessly across screens and runways. Their influence is clear, even as questions of power, authorship, and access remain unresolved.

Despite institutional inertia, Black models continue to reshape fashion’s visual language from within. From Adut Akech’s sustained presence on international runways to a new generation of African and diasporic models redefining casting norms, their work accumulates into something larger than any single season.

As Black History Month progresses, we are reflecting on the Black models who shaped fashion as we know it today across decades, and their sustained presence that moved through an industry that rarely moved in step.

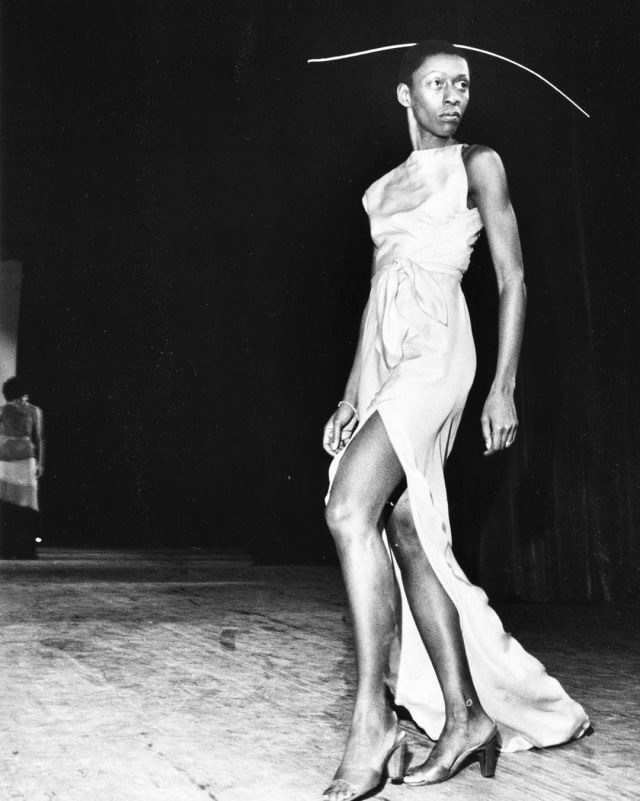

Bethann Hardison

Emerging in the late 1960s, Bethann Hardison became one of the first high-profile Black models in the U.S. Her early career reached a turning point in 1973 at the Battle of Versailles, a historic runway event that placed American designers and a group of Black models on an international stage. For many in attendance, it was the first time models of colour appeared on runways of this scale.

Hardison’s walk during Stephen Burrows’ segment became one of the evening’s defining images. Wearing a canary-yellow gown, she reached the end of the runway, dropped its train to the floor, and held her position, meeting the audience’s gaze without movement. The gesture disrupted the formality of the show and electrified the room. From there, Hardison’s modelling career accelerated within an industry that continued to treat Black models as exceptions.

By the mid-1970s, her work extended beyond the runway. Hardison moved into creative direction and production, collaborating with designers including Stephen Burrows, Kansai Yamamoto, Issey Miyake and Valentino Couture. Her involvement with Valentino connected her to Manifattura Tessile Ferretti, at the time a key swimwear licensee for leading Italian fashion houses, placing her within the mechanics of global luxury.

In 1980, Hardison joined the newly formed Click Models, where she helped reshape approaches to representation and career development. During her tenure, she worked with emerging talent who would later become industry fixtures, including Whitney Houston, Talisa Soto, Tahnee Welch and Elle Macpherson. Four years later, she founded Bethann Management, an agency built on an expanded understanding of beauty and opportunity. Beginning with seven models, the agency grew to represent more than seventy-five men and women across racial and ethnic backgrounds. The focus was structural presence and sustained careers rather than symbolic inclusion.

That same commitment guided her co-founding of the Black Girls Coalition in 1988 alongside Iman. Initially created as a space for connection and collective support among Black models working in high volume at the time, the group quickly evolved into an advocacy network. With members including Naomi Campbell, Veronica Webb, Karen Alexander, Roshumba, Beverly Peele, Cynthia Bailey, and others, the Coalition addressed issues ranging from racism in advertising to broader social inequities affecting Black communities.

Over time, Hardison became one of fashion’s most direct and consistent advocates, openly challenging designers, editors, and institutions to confront racial exclusion within their systems. Her work has continued to expand, encompassing runway accountability, support for emerging designers, and directing and film projects that examine fashion’s cultural power.

Her influence remains ongoing. Through decades of sustained intervention, Hardison has shaped fashion by insisting it accounts for the labour and presence it depends on. The recognition she has received throughout her career shows the scale of her impact and the enduring relevance of her voice.

Katoucha Niane

Born in Dakar, Katoucha Niane was a Guinean model and activist who entered fashion in the 1980s with a presence that resisted containment. Often referred to as the Peule Princess, she was among the first African models to move through European fashion at scale. Her career began in France, where she was first noticed by Jules-François Crahay at Lanvin. Initially hired as a fitting model, she quickly transitioned onto the runway. By the mid-1980s, Katoucha was walking for Thierry Mugler, who later made her one of the faces of his Spring/Summer 1988 campaign. Her work soon extended across the major houses of the era, including Azzedine Alaïa, Christian Dior, and Paco Rabanne.Katoucha’s presence reached a defining moment when she became the face of Yves Saint Laurent, succeeding Rebecca Ayoko and cementing her position within the highest tier of couture. As a muse to both Saint Laurent and Jean Paul Gaultier, she occupied fashion’s most rarefied spaces, and throughout her career, Katoucha refused the expectation that African models explain themselves. She moved through runways and magazine covers declining the burden of translation frequently imposed on Black bodies in European fashion.

In the mid-1990s, Katoucha stepped away from full-time modelling to explore other ventures, including launching a fashion line in Paris for a season. She later appeared as a juror on the French television programme Top Model and, in 2006, founded Ebène Top Model in Dakar. The competition was created to support and platform emerging African models and provide industry access.

Beyond fashion, Katoucha’s commitments extended into activism. She was a vocal advocate for women’s rights and dedicated significant effort to raising awareness around female genital mutilation. Through collaboration with non-governmental organisations and the founding of Katoucha Pour la Lutte Contre l’Excision in Senegal, she worked to advance education and protection for women and girls. Katoucha Niane’s legacy rests in the convergence of beauty, politics and conviction.

Naomi Sims

Born in 1948, Naomi Sims encountered repeated rejection from modelling agencies, some of which told her directly that her skin was too dark for their books. Rather than waiting for permission, Sims bypassed the gatekeepers altogether. Her breakthrough came through direct collaboration with photographers. In 1967, Gösta Peterson photographed her for the fashion supplement of The New York Times, marking a rare moment of mainstream visibility that reframed how Black women could be seen within fashion media. The image shifted perception, and momentum followed.

Soon after, Sims was selected for a national television campaign for AT&T, wearing designs by Bill Blass. The campaign propelled her into international recognition, and by the end of the decade, she had become the first African American model to appear on the covers of Ladies’ Home Journal and Life magazine. These milestones signalled a broader cultural shift in who could occupy the centre of American visual culture.

Sims’ influence extended beyond the runway. In 1973, she shifted from modelling to launch her own business, beginning with a wig line designed to reflect the texture and reality of Black hair. The venture was both commercial and corrective, responding to a market that had long continued to fail Black women.Sims also went into publishing. Beginning with All About Health and Beauty for the Black Woman in 1976, she authored several books focused on care, confidence and professional success with All About Hair Care for the Black Woman and All About Success for the Black Woman. This positioned her at the forefront, especially at a time when Black women were rarely addressed directly by the beauty industry.

Alongside her business ventures, Sims remained engaged with community work, supporting initiatives for young people, veterans and civil rights organisations. Across these efforts, she embodied a philosophy that extended beyond aesthetics. Her career asserted that Black beauty deserved visibility, investment, and care on its own terms. Naomi Sims helped establish a model of influence that reached past fashion’s surface. Through image, enterprise, and advocacy, she gave shape to the idea that Black visibility could also mean Black ownership, agency and self-definition.

Beverley Johnson

While studying at Northeastern University, Beverley Johnson began modelling during a summer break in the early 1970s, quickly securing editorial work that led to a steady rise through fashion media. In August 1974, she became the first Black woman to appear on the cover of American Vogue. This was a seismic shift in fashion’s visual politics and American editorial culture, and its impact was immediate. Within a year, Black models were appearing with greater frequency across U.S. fashion houses, showing a change in industry practice at the time.

Johnson’s career accelerated through the mid-1970s as she appeared on dozens of magazine covers, including a second Vogue cover and a solo cover for Elle, another first for a Black model. She moved fluidly between editorial and runway, working with designers including Halston, Ralph Lauren, Calvin Klein, and Oscar de la Renta.

Johnson transitioned into entrepreneurship early, developing beauty and hair ventures, and in the 1990s, she expanded into lifestyle branding. She has maintained a visible presence on the runway while turning toward advocacy. Through initiatives such as “The Beverly Johnson Rule” launched in 2020, she has continued to press fashion, beauty and media institutions toward measurable diversity commitments.

Iman

Discovered in the mid-1970s, Iman quickly became one of fashion’s most sought-after faces. Her work with photographers such as Irving Penn, Herb Ritts, and Richard Avedon placed her within the highest ranks of editorial fashion, while designers including Yves Saint Laurent and Gianni Versace embraced her as a muse.

Iman’s modelling career unfolded across runways and campaigns for houses like Halston, Givenchy and Chanel. She appeared on multiple Vogue covers and became emblematic of a shift in how African beauty could exist within Western luxury without explanation or performance. Yet even as she occupied fashion’s most elite spaces, Iman remained acutely aware of the industry’s racial mechanics. Having grown up in a country where Blackness was not marked as difference, she was struck by the way fashion insisted on categorising and limiting Black models as a separate class.

In response, Iman helped reshape fashion’s internal politics. Alongside Bethann Hardison and Naomi Campbell, she co-founded the Black Girls Coalition in 1988, an initiative that challenged tokenism and encouraged collective visibility over competition. The group’s work extended beyond symbolism and leaned into directly confronting designers and institutions when casting practices showed exclusion disguised as trend.

After retiring from modelling in 1989, Iman launched Iman Cosmetics to address the beauty industry’s refusal to cater to darker skin tones. The brand became both corrective and precedent-setting. Alongside her business work, Iman has remained deeply engaged in humanitarian efforts, serving as a global ambassador for organisations addressing emergency relief and health crises.

Naomi Campbell

Scouted as a child, Naomi Campbell’s career unfolded alongside the rise of the supermodel era, where she stood shoulder to shoulder with Cindy Crawford, Linda Evangelista, Christy Turlington, and Claudia Schiffer. Their collective presence defined fashion in the early 1990s, crystallised in moments like George Michael’s Freedom! ’90 video, which blurred the lines between runway, celebrity and pop culture. Campbell’s success was expansive in scale. She went on to work with nearly every major fashion house, appeared on hundreds of magazine covers, and in 1997 became the first Black woman to open a Prada show, shifting long-held hierarchies within European luxury.

Decades into her career, Campbell’s influence has only sharpened. In 2018, she received the CFDA’s Fashion Icon Award, acknowledging both her longevity and impact. In 2024, London’s Victoria and Albert Museum opened Naomi: In Fashion, the first major museum exhibition devoted to a single fashion model, placing her work within an institutional archive usually reserved for designers. Campbell’s career demonstrates how sustained presence can evolve into cultural authority, and expand the limits of what fashion is willing to preserve, celebrate and remember.

The groundwork laid by these earlier pioneers, and the generations after, have carried forward through figures who’ve expanded Black modelling into new forms of influence. Iman, through her beauty brand, exposed the industry’s long-standing failure to serve Black consumers, even as it continued to profit from Black aesthetics.

Bethann Hardison, Naomi Campbell and Iman together formed the Black Girls Coalition in 1988, which shifted conversations from inclusion as image to inclusion as practice — publicly urging major fashion houses to commit to using Black models at a structural level rather than as seasonal gestures. Beverly Johnson’s historic appearance on the cover of American Vogue marked another decisive shift. Her success with European designers such as Hubert de Givenchy and Yves Saint Laurent signalled a widening of fashion’s visual language, influencing casting practices as brands increasingly placed Black models at the centre of their collections.

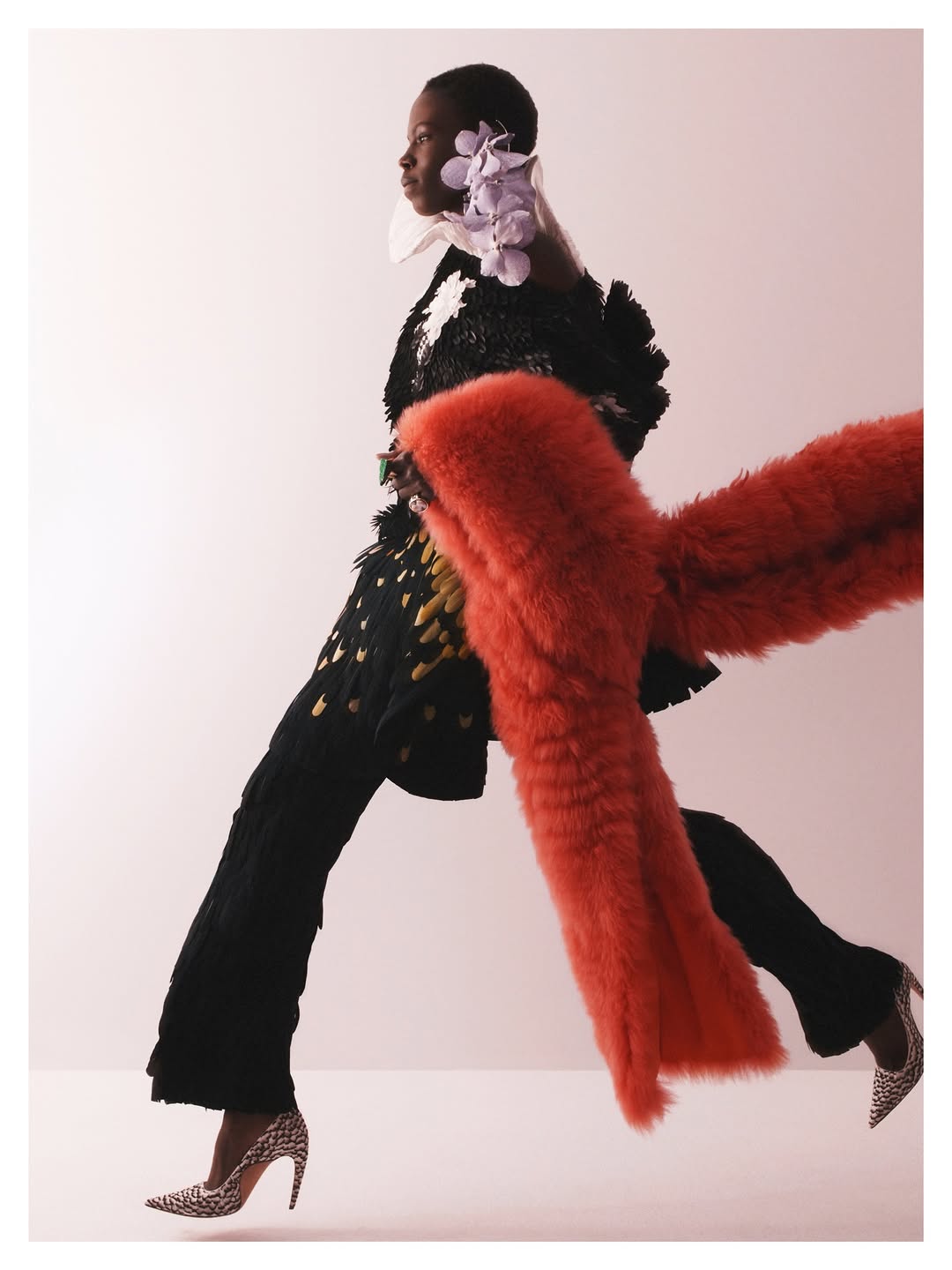

Today, Black models continue this lineage from within the global fashion system. Their presence circulates across runways and campaigns in fashion capitals worldwide, shaped by a legacy built through decades of intervention and refusal. This presence, however, remains uneven and provisional. Recent Milan and Paris Fashion Weeks offer a clear example, where the return to narrow, racialised aesthetics at houses such as Dolce & Gabbana shows how quickly the industry reverts once scrutiny fades. Progress is still measured through moments and milestones rather than sustained shifts in casting power, creative control and authorship.Taken together, these figures show Black modelling as an ongoing practice of expansion, one that continues to reshape fashion’s visual language from within.

Haute Couture Spring/Summer 2026 in Paris seemed to press its ear to the ground. Across the runways, there was a collective turning toward the earth — not necessarily as a literal landscape, but as a source of texture, direction and meaning. Dior, Chanel, and Schiaparelli each arrived at this impulse differently, but together they traced a shared desire to root fantasy in something organic: the floral, the whimsical, the otherworldly. Couture, which is often imagined as untouchable, felt distinctly alive and unearthed.

At Dior, the earth bloomed. Jonathan Anderson’s couture debut framed the natural world as a question of form, volume and internal logic. Drawing from the ceramic work of Kenyan-born British potter Magdalene Odundo, the collection approached couture through sculpture rather than garment-first thinking. Lightness was a technical challenge instead of a visual effect. Rounded silhouettes and projecting forms were developed through extensive prototyping, with the atelier working alongside specialists from architectural disciplines to engineer internal frameworks capable of holding shape without weight. Materials such as piano wire and densely gathered tulle formed unseen architectures beneath the surface.

Then came the flowers.

Floral elements appeared insistently and everywhere, not as embellishment but as connective thread through the entire collection. They surfaced as earrings, bloomed across dresses, emerged on shoes, and threaded the collection together in full saturation. Embroidery and flower-making operated structurally, binding the looks into a single ecosystem rather than isolated statements. Anderson did not reference nature sparingly; it was cultivated until the collection felt entirely in bloom.

The collection was presented alongside an exhibition at the Musée Rodin that placed Anderson’s designs in dialogue with Dior’s archive and Odundo’s ceramics, and the collection positioned couture as a fine practice of material inquiry.

Chanel’s Haute Couture presentation was lighter, more mischievous in comparison to Dior. Under Matthieu Blazy, whimsy operated as a form of logic, guiding how the clothes moved, hovered and dissolved on the body. Feathers suggested motion, proportions gently disrupted expectation, and surfaces carried the impression of air even at rest. Tweeds, which is long central to the house, were subtly dyed to echo owl feathers, while a cocoon dress with rounded brown sleeves and a ring of red at the neckline recalled the markings of a woodpecker. Elsewhere, peacock prints, beetle-like volumes, and their repeated motifs resembling hand-drawn feathers or scales reinforced the collection’s natural references.

This lightness was carefully constructed. Feather effects were achieved through cut-thread embroidery and layered applications instead of leaning into literal volume. Painted organza and meticulously dyed tweeds required precise control to maintain softness and still hold its structure. Bead embroidery was used sparingly, catching light without anchoring the garments visually. The mood was dreamlike but grounded, and shaped by simplicity and precision. Couture at Chanel narrowed its focus, stripping back to essentials and allowing craftsmanship to speak through restraint.The garments themselves appeared effortless. However, that ease risks being misread as the opposite of couture, so it depends on exacting control. Blazy’s Chanel proposed a form of couture rooted in observation and material intelligence, and the fantasy was able to emerge through this refinement.

Schiaparelli, as expected, left the ground entirely (but remained tethered to it in spirit). In his show notes, Daniel Roseberry traced the origin of the season to a visit to the renowned Sistine Chapel in Vatican City, where, in contrast to narrative painting that instructs, Michelangelo’s ceiling suspends meaning and privileges feeling. What mattered, Roseberry notes, was not representation but response. The collection took shape around that shift, asking not what couture should look like, but how it should feel.

That recalibration translated into silhouettes built around tension and excess. Roseberry described the central figures of the collection as “infantas terribles,” creatures drawn from scorpions, snakes, and birds, with their aggression woven directly into form. Sharp strokes became stingers, squiggles hardened into tails and teeth. These looks pushed upward and outward, treating couture as something that defies gravity and not clothing that necessarily conforms to the body.

The technical execution justified the scale of the fantasy. Lace was hand-cut and sculpted into bas-relief to create depth and shadow. Feathers appeared both real and simulated, painted, airbrushed, dipped in resin or crystallized. Neon tulle was layered beneath lace to produce a softened, atmospheric effect. Each look was built around a named identity, from “Isabella Blowfish” to jackets saturated in the colors of birds of paradise. Accessories extended the mythology, with artificial bird heads rendered in silk, resin, and pearl, nodding to Elsa Schiaparelli’s longstanding fascination with animal life.

Schiaparelli’s contribution to the season embraced nature as something volatile and theatrical. Roseberry leaned into excess, sensation, and transformation. The collection argued for couture as an emotional instrument, one that uses extreme craft to grant permission to feel rather than just explain.

Together, these collections were literally and figuratively grounded but somehow offered escape. Not escapism detached from reality, but a re-enchantment of it. The sources were clear: imagined gardens and creatures, distant lands, and unfettered creativity. What anchors these visions collectively was not fantasy alone, but the labor of it all. Each look is a record of thousands of hours spent in the ateliers, shaped by the hands of artisans whose expertise turns ideas into the pieces displayed. In couture, imagination only becomes real through devotion.

This season reignites one of fashion’s oldest debates: where does the fantasy of haute couture truly reside? Is it in theatrical gestures, dramatic silhouettes and spectacle? Or does it live in something more restrained — an invisible excellence, a technical precision so refined it borders on the impossible? Chanel’s subtler showing this season, in particular, invites this question. Can restraint itself be fantastical when the craftsmanship is flawless?

“So many people ask me what the point is of couture. It’s certainly not to create clothing for daily life. But for me, couture allows me to connect with the hopeful adolescent I once was, the one who decided to not go into medicine or finance or law, but to chase that singular fantasy that fashion can still provide,” said Daniel Roseberry in his notes for Schiaperreli’s The Agony and the Ecstasy.

This discourse matters because couture is so often misunderstood. Its value is not determined by trend cycles or runway theatrics, but by method and imagination stretched far and wide. Haute couture is defined by process, by artisanal construction, inherited techniques, and a standard of execution that cannot be replicated at scale. These garments are built, not assembled. Their language is hidden in seams, linings and structures the eye may never even fully see. Chanel’s SS26 collection makes this distinction especially clear. Here, labor is deliberately concealed rather than staged. Techniques like calibrated dyeing, cut-thread embroidery, feather work and material layering operate beneath the surface. The absence of overt drama does not signal ease, but discipline, and reflects a couture tradition where mastery can be measured by control and restraint.

Couture has never been about realism or utility. It exists as a space of projection, where imagination, obsession and labor are taken to their furthest edge. What justifies couture is not its wearability, but its insistence on doing things at a scale that resists efficiency. In an industry increasingly driven by speed, replication and disposability, couture remains one of the last places where time itself is treated as a material.

And so, as SS26 couture drew from flowers, fauna, and imagined worlds, its foundation remained largely unchanged. Haute couture continues to operate at the intersection of fantasy, discipline, vision and technique. It preserves ways of making that would otherwise disappear. Couture sets a benchmark for what craft can be when it is not optimized into trend or productivity. Its value lies in refusal: a refusal to rush, a refusal to flatten ideas and a refusal to allow skill to become obsolete. It’s rooted in craft and shaped by human hands, and continues to reach beyond the possible, holding space for imagination to become something timeless.

While the fierce final between Senegal and Morocco unfolded on the pitch in Rabat, a parallel celebration of football culture kicked off in the backstreets of London.

Dubbed "The Kickback," this event was more than just a watch party; it was a vibrant, organic convergence of fans, fashion, and rhythm that transformed a local rivalry into a unifying celebration of African football and street culture. Held in a converted warehouse space, The Kickback served as a cultural hub, drawing in a diverse crowd of London's creative youth, football fanatics, and culture curators. Amidst the electric atmosphere, the humble Chuck Taylor’s emerged, not by design but by consensus, as the unofficial uniform of unity.The Uniform: Chucks as the Common Ground.

As the London sun set and the crowd swelled, the dress code became an unspoken statement. One element was universal: classic Chuck Taylors. From the high-top 70s vintage to the worn-in low-cut originals, they were a spectrum of different styles, colours, and conditions, each pair telling its own story. The sneaker, a global symbol of effortless cool and creative rebellion, transcended national loyalties and became a neutral territory where fan identity met streetwear chic. The sheer ubiquity of the shoe proved that off the pitch, style was a shared, accessible language for everyone at The Kickback. It subtly underscored the event's ethos: a focus on shared culture over fierce competition.Panel Insight: Culture, Career, and Community

The evening’s energy was momentarily redirected by a dynamic and insightful panel discussion, expertly hosted by the celebrated culture commentator, Kenny Jonathan. The conversation brought together a trio of accomplished professionals— Fashion Stylist Algen Hamilton, Footballer Josh Nichols, and Marketing agent Subomi Odanye.

The discussion delved deep into the panellists' respective career journeys, offering invaluable firsthand accounts of their experiences, the pivotal lessons they have learned along the way, and the challenges they have overcome to achieve success in their highly competitive fields. They spoke candidly about navigating their industries, from securing initial opportunities to establishing a unique professional voice.

A central theme of the talk was the profound importance of culture—not only as a broad societal concept but as a defining, intrinsic element of their personal and professional identities. The panellists articulated how their cultural backgrounds—Nigerian, Ghanaian, and Jamaican heritage, respectively—have fundamentally shaped their values and morals, informed their creative outlook, and served as a constant source of inspiration and resilience. They discussed the interplay between their heritage and their work, highlighting how this synergy has enabled them to create authentic, nuanced, and impactful work within their fields, stressing that authenticity is the ultimate currency.

Furthermore, the discussion offered a crucial, forward-looking perspective, providing the audience—particularly the new generation of creatives—with a clear foresight into the potential impact of their current endeavours. Hamilton, Nichols, and Odanye shared their collective vision for how the work they are doing today is contributing to a meaningful, positive shift within their communities. Their goal was clear: to inspire, mentor, and actively open doors for aspiring creatives who share similar backgrounds. The talk served as a powerful testament to the idea that professional success and cultural identity are deeply interwoven, and that a commitment to both is not merely admirable but essential for driving future innovation and community enrichment across London’s cultural landscape.Atmosphere: More Than a Watch Party

The event was a sensory overload, expertly curated to engage every part of the mind and body. A giant projector screen broadcast the tense, high-stakes match, but the space around it vibrated with its own self-generated energy, making the football only one piece of a larger cultural mosaic:

● The Soundtrack: The air was filled with an expertly layered musical journey. DJs seamlessly blended the complex, polyrhythmic beats of Senegalese mbalax with the hypnotic, driving rhythms of Moroccan music, creating a unique cross-continental soundscape. As halftime hit, the vibe shifted to a unifying burst of Afrobeats and Amapiano to keep the balance, guaranteeing continuous movement.

● Culinary Corner: The pop-up food stations were a celebration of London's diverse culinary scene. Offerings included authentic Nigerian cuisine from Tasty's, a highly-regarded local catering business, standing alongside Nando's, the iconic UK food staple. This blending of local entrepreneurship with mainstream favourites mirrored the crowd’s own diversity.

● The Real Competition: The most heated competition wasn't always on-screen but at the table football arena. Teams, often comprised of Moroccan and Senegalese supporters, battled for bragging rights settled in quick, friendly, and intensely competitive tournaments, proving that camaraderie could win over rivalry.

The Final Whistle & A Shared Vibe

When the controversial final whistle blew on screen, marking the end of a chaotic match, a complex, suspended silence fell momentarily over The Kickback. For a brief, shared instant, the tension and disappointment from the final were palpable. Then, with a deft touch of cultural therapy, the DJ dropped a timeless classic track—a unifying anthem that transcended the match result. The crowd erupted, not in protest, but in collective dancing. The Chuck Taylors, now slightly dusty and scuffed from a night of movement and celebration, kept rhythmically moving on the warehouse floor.

Background on the Match: The final between Morocco and Senegal was poised to be a historic celebration of African football's ascent. Instead, it will be remembered for one of the most chaotic and controversial endings in the tournament's history. On January 18, 2026, at the Prince Moulay Abdellah Stadium in Rabat, Senegal defeated host nation Morocco 1-0 in extra time to claim their second continental title. However, the hard-fought victory was completely overshadowed by a stoppage-time walk-off protest by Moroccan players, violent fan clashes in the stands, and a shocking, high-stakes penalty miss that added to the deep drama of the night.

The Kickback demonstrated that football's true, enduring spirit flourishes far from the stadium lights—it's found in the vital, community-building space it creates. It’s a space where a shared love of the game is merely the launchpad for a deeper cultural conversation. Much like the panellists discussed, this event affirmed that a commitment to one's cultural identity and community is the essential foundation for innovation and building a path for the next generation. This convergence allowed attendees not just to witness a match, but to connect with each other, feel inspired by the stories of creatives, and embrace a moment of collective belonging. The Chuck Taylors, scuffed and worn by the night's end, weren't merely shoes; they were the visible common ground at an unforgettable party, cementing The Kickback as a vital, inspiring fixture in London's cultural calendar.

Art as survival mechanism, not aesthetic choice — this is the foundation Daneil Oshundaro builds from. The visual artist approaches creation the way some people approach prayer: as a necessary translation of what cannot be spoken, a processing of emotion and memory that refuses the luxury of looking away. His work exists in the space between pain and resilience, between what we show the world and what we carry alone.

Oshundaro's practice rejects beauty for beauty's sake. Instead, he mines the quiet battles — loneliness, faith, inner conflict, the weight of being misunderstood. There's a deliberate stillness to his approach, a patience that insists strength doesn't announce itself but reveals itself slowly, honestly. In a cultural moment saturated with surface-level engagement, his work asks viewers to do something increasingly rare: slow down and feel.

What makes his perspective particularly vital is the recognition that art changes people internally before it changes anything externally. It's infrastructure thinking applied to emotional work — the understanding that lasting impact starts with individual shifts in how we see ourselves and each other. This conversation explores how Oshundaro translates the unsayable, why meaning matters more than fleeting beauty, and what it means to create art that refuses to let viewers remain numb.

Can you introduce yourself and tell us a little about who you are as an artist?

I'm an artist who works from emotion, memory, and survival. My work is rooted in lived experience — pain, resilience, faith, and the search for meaning in a world that often feels numb. I don't create just to make something look beautiful; I create to tell the truth. Art for me is a way to translate what can't always be said out loud.

What inspired this piece or project?

This piece was inspired by the quiet battles people carry — the things we hide behind smiles, social media, or silence. I wanted to make something that speaks for those moments when you feel unseen, unheard, or misunderstood. It comes from observing life, relationships, struggle, and the tension between who we are and who the world expects us to be.

What themes or messages do you explore through your work?

My work explores identity, loneliness, faith, inner conflict, and emotional survival. I'm interested in how people break, how they rebuild, and how they search for purpose. A recurring theme in my work is the idea that strength is not loud — it is quiet, patient, and deeply human.

How does your art connect to action or change?

I believe art changes people internally before it changes the world externally. When someone feels understood by a piece of art, they start to reflect, question, and sometimes heal. That inner shift leads to real change — in how they treat themselves, others, and the world around them. My work invites people to slow down and feel, and that is a powerful form of action.

Why is it important for you to create art with meaning or impact?

Because empty beauty fades. Meaning stays. I want my work to leave something behind in the viewer — a memory, a question, a feeling, a moment of recognition. Art saved me in many ways, so I create with the hope that it can do the same for someone else.

Can you share a moment or experience that shaped you as an artist?

There were moments in my life when I felt completely alone, even when surrounded by people. Creating art became a way to survive those moments. Instead of shutting down, I started pouring everything into my work — fear, hope, faith, confusion. That's when I realized art wasn't just something I do. It's something that keeps me alive.

.jpg)

What do you want people to know about you beyond your art?

Beyond my work, I am someone who believes deeply in truth, growth, and faith. I am constantly learning, questioning, and trying to become a better human being. My art may be intense, but it comes from a place of love — a desire to understand life, people, and God more deeply.

When people talk about Salsa, it’s often framed as something light, music for dance floors, glossy ballroom lessons, a genre boxed neatly into “Latin”. But sitting with it long enough, really listening and researching, you begin to realize that Salsa is anything but light. It is heavy with memory. It carries the weight of oceans crossed in chains, of languages stolen, of bodies displaced, and of cultures that refused to disappear. To engage Salsa during Black History Month is to confront it deeply as evidence that African culture survived the most violent rupture in modern history and found ways to speak again—through rhythm, through movement, through sound. Salsa is neither a New York invention in the shallow sense, nor is it solely Cuban, Puerto Rican, or Caribbean. It is diasporic. It belongs to the long, unfinished story of Black survival across the Atlantic world.

Long before the word “Salsa” existed, before the Caribbean was even imagined as a destination, rhythm already governed life in West and Central Africa. Among the Yoruba and Bantu peoples, music was not separate from the spiritual or the social. Drums were communicative. They marked births, deaths, harvests, war, and prayer. Rhythm held time itself. When Africans were captured and transported across the ocean, colonial systems worked tirelessly to sever them from this world, to rename them, convert them and silence them. But rhythm is not something you can confiscate. It lives in the body. It survives in muscle memory, in breath more so in instinct. That survival is most clearly heard in the clave. The clave is the governing logic of Salsa. It dictates when a phrase can begin, when it must resolve, and when it should wait. Its five-beat structure mirrors West African bell patterns used in sacred ceremonies, and its persistence is a quiet show of resistance. Even when enslaved Africans were banned from drumming outright, the rhythmic sensibility remained, finding new ways to surface.