On this continent, beauty begins with the hands. Hands that part, oil, and weave. Hands that have memorized the language of hair, speaking through sections, patterns, and gentle tugs. Across Africa, from Dakar to Lagos, Addis to Accra, braiding isn’t just adornment. It is history performed, lineage retold, and love translated through touch.

Some of my earliest memories are of sitting between my mother’s knees, my head tilted slightly forward, the smell of hair oil filling the room. The TV would be playing softly in the background, and I’d try to keep still while sneaking glances at the screen. Her fingers moved with a rhythm that felt ancient, parting, stretching, weaving. I didn’t know it then, but those moments were history being repeated. Every tug was a lesson. Every braid, a continuation.

Across Africa, this scene plays out in a thousand different forms, in courtyards and living rooms, on verandas and under mango trees. Women gathered in circles, talking, laughing, braiding. The air thick with stories, with gossip, with a kind of closeness that doesn’t need words. The scent of shea butter and coconut oil mixes with heat and conversation, that familiar rhythm of community. The act of braiding connects us: grandmothers to mothers to daughters, women to women. Each plait a mark of belonging, each pattern a reflection of where we come from.

I’ve always believed that the hands of African women are sacred. They remember things our mouths have forgotten how to say. They can heal, create, and restore. In the simple act of braiding, there’s patience, love, and artistry. The same hands that cook, nurture, and build are the ones that part each line with intention, making order out of something wild.

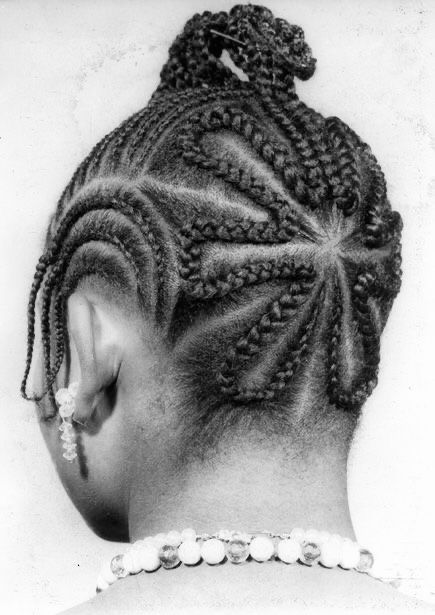

Our hairstyles were once maps, status symbols, identity markers. The Fulani braids with their beads and centre parts, Yoruba threading, Himba ochre-coated locs, each design a language of its own. Braiding told stories before we could write them down. It said who we were, what we believed in, where we belonged. Even now, when I walk into a salon in Lagos or Dakar, that history hums beneath the chatter and the hair dryers. Every woman there is part of something bigger, a lineage of women who’ve turned creativity into culture, care into legacy.

When I grew older and started braiding my own hair, I realised how much I had inherited. Not just the skill, but the meaning. Braiding felt like communion, a small ritual that reminded me where I came from. The hands changed, the tools evolved, but the essence remained the same. To braid another’s hair is to honour her, to say, I see you. I care for you. You are part of something that began long before both of us.

In today’s cities, African women continue the ritual, under balconies, in salons, in student dorms, in living rooms filled with laughter and TV noise. The same patterns that once adorned queens and warriors now travel across oceans, reimagined yet rooted. The beauty is not just in the style but in the survival, how something so ancient still feels modern, still feels like home.

Because African beauty has always been deeper than decoration. It’s how we preserve ourselves in a world that keeps changing, through hair, through skin, through the small acts that remind us of who we are. There’s something holy about it, how a braid can hold time, identity, and tenderness all at once. When we braid, we keep memory alive. We say: we were here, we have always been here, and we will keep creating beauty out of our becoming.