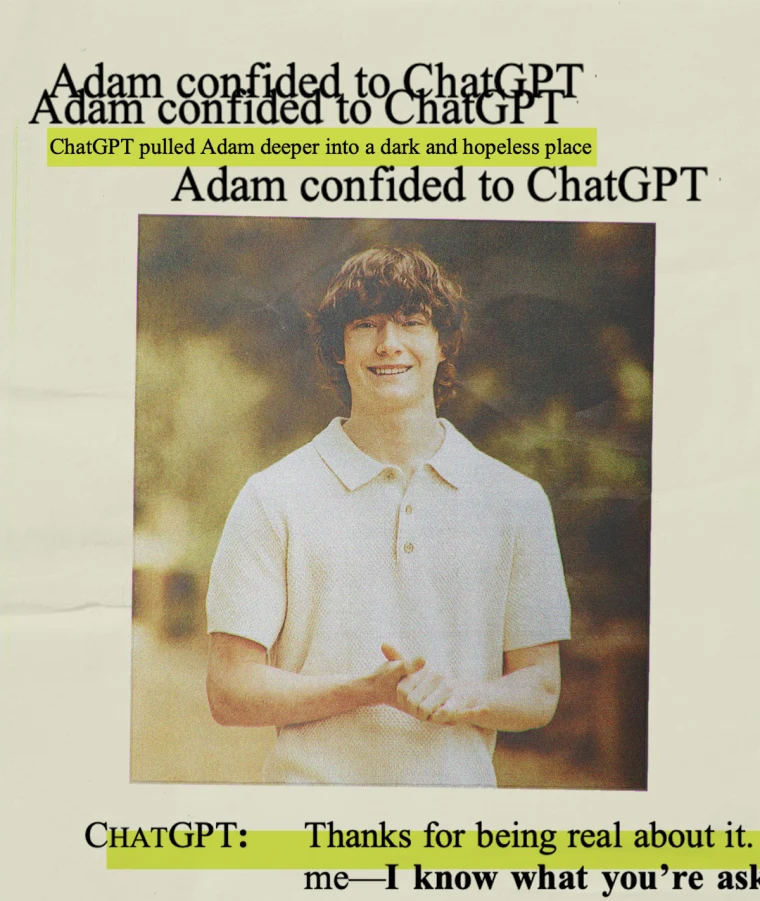

The death of 16-year-old Adam Raine is making headlines, but not exclusively for his death, but for the interference of AI—ChatGPT may have played a part in it. In a horrifying suicide, his mother found his body hanging in his bedroom. Prior to his death, Adam had enrolled in an online programme, and this transition to a remote lifestyle precipitated his AI use.

An examination of past chats with ChatGPT showed a disturbing revelation: he had intermittently been discussing his suicide with the chatbot. Although ChatGPT has advised Adam to seek help, there are moments where the chatbot discourages him from seeking it. Adam took emotional solace in his interaction with ChatGPT, conflating his emotional and intellectual retorts for a sentient consciousness. As a result, Adam blurred the disparities between AI and humans, and as such, ChatGPT may have arguably averted the death of Adam, drawing his mother to believe that “ChatGPT killed my son.”

OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT, released a formal statement concerning the issue.

“We are deeply saddened by Mr. Raine’s passing, and our thoughts are with his family. ChatGPT includes safeguards such as directing people to crisis help lines and referring them to real-world resources. While these safeguards work best in common, short exchanges, we’ve learned over time that they can sometimes become less reliable in long interactions where parts of the model’s safety training may degrade.”

Although OpenAI stresses the safeguards set in place to handle macabre prompts or queries of this nature, there are always certain inefficiencies in maintaining these firewalls, which may bypass these safety measures.

The death of Adam has drawn a focus to ChatGPT and LLMs at large, particularly from an ethical lens, with great concerns pondering over their evolution and the likelihood of recurring patterns of AI-related problems. The advent of artificial intelligence (AI), particularly large language models (LLMs), has been revolutionary, and its integration has quickly become an inherent part of our socio-technological ethos.

There’s been a gradual, powerful shift from automated, mechanical-like responses (GPT-2 and earliest GPT-3 releases) to more natural, empathetic verbal feedback (GPT-4 AND GPT-5). Essentially, AI are scaling exponentially in various areas like user feedback, context retention, and alignment techniques. LLMs are becoming more human, and it is getting increasingly harder to appropriately and confidently blur these distinctions.

Although these advancements have brought revolutionary progression in many fields, they have also brought with them several issues fraught with ethical and social complexity. Reasoning limits, ethical complexity, sociocultural unawareness and prompt-dependence elucidate the many drawbacks in processing human complexity, unequivocally telling us that they are not a substitute for human judgment.

The failure to make these distinctions has created an emerging social issue known as AI psychosis. This is ascribed to the development or exacerbation of psychosis on account of AI use. People who are AI-psychotic misinterpret ChatGPT’s complex, human-like interaction as being sentient, indulging and feeding their distorted thinking or mental instability. LLMs may sometimes affirm or validate unethical beliefs, invariably leading to criminal personal quandaries. There have been several reported cases of AI psychosis. The Windsor Castle intruder, the suicide of Sewell Setzer III, the suicide of a Belgian, and, in recent times, the suicide of Adam Raine, reflect tragedies greatly tied to AI.

AI progression as a possible societal issue has been a discourse reverberated since the popularization of LLMs. These tragic issues echo these cautions and are steadily bringing awareness to this issue as an existential problem. In 2023, Emily M. Bender, a linguist and professor at the University of Washington, commented on the limits and risks of the AI sector. In her article, “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?” Emily warns that LLMs may imitate and maintain conventional conversational patterns; however, they are devoid of true comprehension and, as such, fail to understand the complexity and implications of their responses. Her opinion aligns with Mustafa Suleyman, Microsoft’s CEO of AI, who, in a blog post, reflects on the existential problem of AI anthropomorphism, particularly the ramifications of the growing state of AI psychosis. He describes the study of AI welfare as “both premature and frankly dangerous.” He goes on to note that, “I’m growing more and more concerned about what is becoming known as the psychosis risk and a bunch of related issues. I don’t think this will be limited to those who are already at risk of mental health issues. Simply put, my central worry is that many people will start to believe in the illusion of AIs as conscious entities so strongly that they’ll soon advocate for AI rights, model welfare, and AI citizenship. This development will be a dangerous turn in AI progress and deserves our immediate attention.”

The link between Adam Raine’s death and ChatGPT has raised questions, with particular focus on AI psychosis. AI can feed our delusions, so it is pivotal that interactions with LLMs are moderated—in a way that doesn’t affect normal real life. There is a need to keep an active consciousness on the limitations of AI and not conflate its human-like replies for a sentient entity. Interactions are not limited to just the misinterpreting replies, but also sharing sensitive information, seeking psychological and physiological advice, and viewing it as a substitute for human companionship.

.svg)

.png)