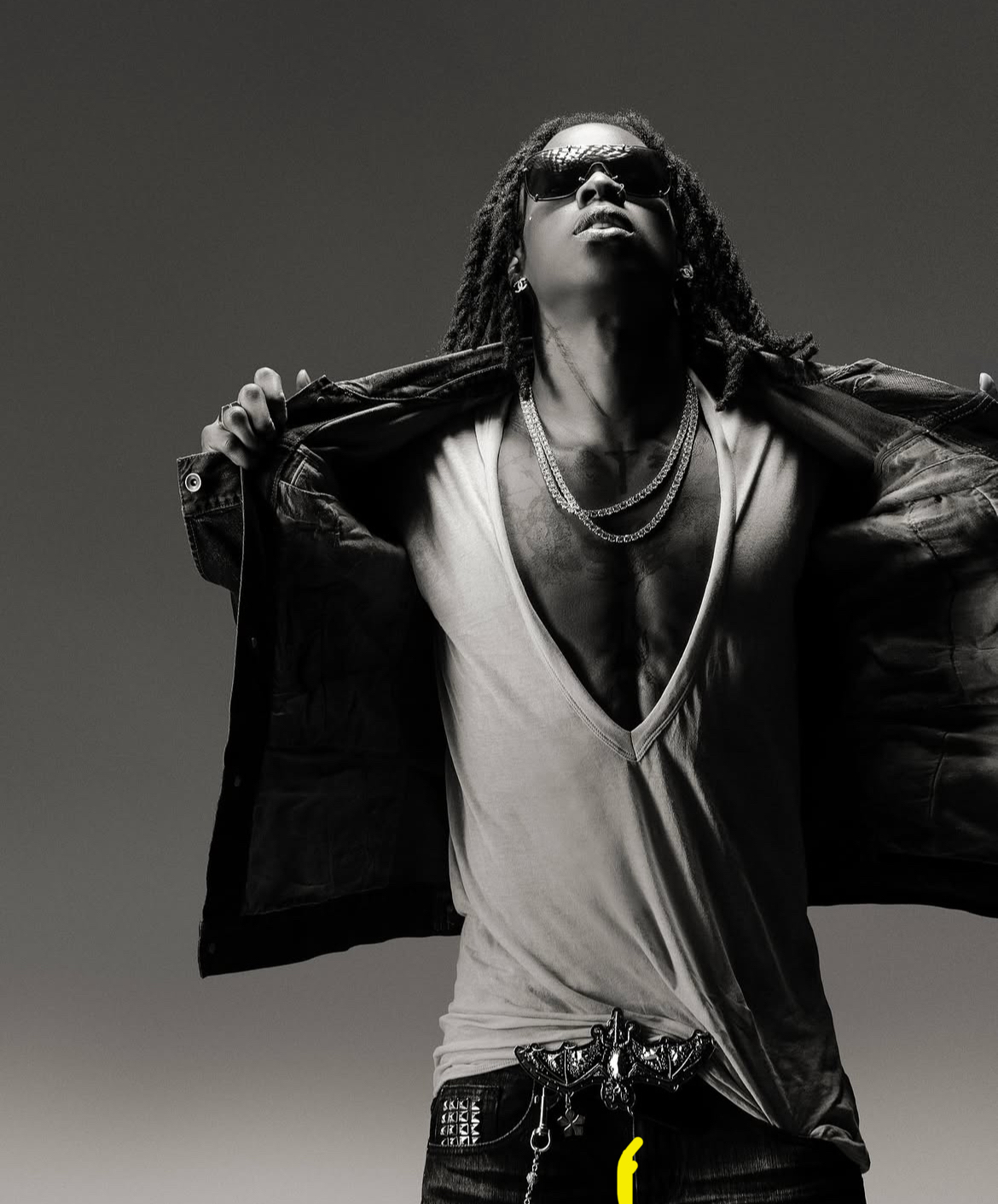

A snippet of the imminent video for Rema’s latest single, Fun, is currently stirring an outpouring of praise online. To illustrate the extent of the chatter it has stirred, the clip has garnered some 13 million views on X in a little over 48 hours. This goes to show how well fans have received the single, in which, over a glassy production that crests and ebbs like an ocean wave, he flattens chatter around his supposed beef with Omah Lay and expresses desire for a pause from the attendant headwinds of celebrity life. “Abeg pass me my cup/ I just want to have fun/ I no wan worry too much,” he sings wistfully. Despite the song’s slow tempo and introspective bent, which become more conspicuous when we consider it against Afrobeats’ current energetic state, dominated by songs like DJ Tunez’ One Condition and Fola’s You, Fun shot up the charts and holds the top spot on the Nigerian singles chart on Apple Music and Spotify. In less than a month of release, the song has racked up over 12 million Spotify streams.

The song’s arrival, a month after Kelebu, a riotous left-field track that reimagines the Ivorian sound Coupé-décalé, however, initially lent an awkward air to the song’s release. Pop artists and their teams, especially A-listers like Rema, typically plan and schedule releases months and sometimes years in advance, spacing them adequately for maximum impact. Rema’s Fun, however, arrived only two days after Kelebu’s video. Rema and his team appear to have been eager, maybe too eager, to move past the song. Why is this, and what interesting insights might we untangle from all of this?

Since its release, Kelebu has steadily tumbled down the charts even though the song was heavily promoted. At some point, it was all you could see scrolling through TikTok or X. The song’s experimental bent earned it infamy and generated conversations from the get-go. But what really catapulted the song to near ubiquity was the $10,000 (15 million Naira) Rema offered to the winners of a dance challenge for the song. Soon after he made the announcement, social media became saturated with whimsical choreographies to the song. Here’s where it gets interesting: the social media challenge became a phenomenal hit; not only did it monopolise the attention economy on TikTok, but it became one of the most talked-about topics on social media. And yet, the song continued to slide down the charts. The song has disappeared from most charts and is arguably Rema’s worst performing song of all time, but it left us with a trove of lessons.

In Wizkid’s Kese, he sings “Anything wey I drop dem go chop aje.” His tone is blithe, assured. His brag echoes a sentiment shared by many artists’ fanbases. If you’re active on social media, you’d probably have run into one too many zealots bragging that even if their favourite artist coughs on a beat, they’ll play it relentlessly. Once an artist crosses a certain threshold of stardom, it’s taken for granted that it’s impossible for a song or project by the artist to completely flop. The commercial performance of Kelebu shatters this assumption. To be clear, Rema’s case is different from a floundering artist: the singles before Kelebu were met with rapturous praise, as was Fun. Kelebu is a rare instance of the market emphatically rejecting a song by one of the most influential artists of our times. This makes it an interesting case study.

“Form follows function” is a modernist design saying that has permeated everyday vernacular. This phrase can be read in two ways. The first is that the appearance of an object should suggest its function. For example, the protruded handle of a doorknob suggests turning, which is how we get a door to open. The other reading of the phrase is more metaphorical and, by effect, more universal. It holds that every form inherently delimits the functionality of a device or structure. Which is a fancy way of saying that every “form” has its limitations. For example, while a doorknob can be turned to open a door, its form precludes other actions like flipping the door upside down, except that the door is faulty or intentionally designed to surprise people with this anomaly.

While this second interpretation of the saying is largely unassailable in the mechanical world, in the world of the arts, it’s less so. In fact, some of the most influential artists earned their reputations by subverting the art forms they practised. Take the impressionists, Paul Ceźanne, Van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, who usurped the then-iron-clad notion that the form of painting ought to render a literal depiction of life. Similarly, the modernist writers of the nineteenth and mid-twentieth centuries entirely pulverised and transformed various literary forms, poetry, the short story, journalism to resemble their amorphous ethos. Writers like Virginia Woolf and Joyce abandoned orderly narration to mimic the unfiltered flow of natural thought. T.S. Eliot and James Joyce likewise repudiated coherent storytelling in favor of fragmented narratives. In music, artists like Nina Simone and Bob Dylan disrupted their respective genres earning acclaim in the process.

Since last year, Rema has been on a mission to disrupt Afrobeats. His 2024 album Heis finds him deploying guttural chants and frenetic drums to this end. Similarly, Kelebu continues in this tradition, pushing the frenetic sound he conjured with Heis to a more intense register. The result is a song that excels at being a window into the possibilities Afrobeats can offer but has little commercial appeal. The reason for this is that while the song is exciting, it’s too jarring to sustain multiple listens. In the era of purchasing music physically, through compact discs or vinyl, Kelebu may have fared better. After all, the song is popular. But in the streaming era, which favours songs that are mellow enough to sustain repeated plays and blend in the background, Kelebu’s unfettered exuberance ultimately became its foil. If Rema demonstrated last year with Heis that subversion and commercial acclaim could coexist, with Kelebu, the lesson is that there’s a limit to which the form, Afrobeats, can be subverted before something, commercial success, begins to give.

.svg)

.png)