When people talk about Salsa, it’s often framed as something light, music for dance floors, glossy ballroom lessons, a genre boxed neatly into “Latin”. But sitting with it long enough, really listening and researching, you begin to realize that Salsa is anything but light. It is heavy with memory. It carries the weight of oceans crossed in chains, of languages stolen, of bodies displaced, and of cultures that refused to disappear. To engage Salsa during Black History Month is to confront it deeply as evidence that African culture survived the most violent rupture in modern history and found ways to speak again—through rhythm, through movement, through sound. Salsa is neither a New York invention in the shallow sense, nor is it solely Cuban, Puerto Rican, or Caribbean. It is diasporic. It belongs to the long, unfinished story of Black survival across the Atlantic world.

Long before the word “Salsa” existed, before the Caribbean was even imagined as a destination, rhythm already governed life in West and Central Africa. Among the Yoruba and Bantu peoples, music was not separate from the spiritual or the social. Drums were communicative. They marked births, deaths, harvests, war, and prayer. Rhythm held time itself. When Africans were captured and transported across the ocean, colonial systems worked tirelessly to sever them from this world, to rename them, convert them and silence them. But rhythm is not something you can confiscate. It lives in the body. It survives in muscle memory, in breath more so in instinct. That survival is most clearly heard in the clave. The clave is the governing logic of Salsa. It dictates when a phrase can begin, when it must resolve, and when it should wait. Its five-beat structure mirrors West African bell patterns used in sacred ceremonies, and its persistence is a quiet show of resistance. Even when enslaved Africans were banned from drumming outright, the rhythmic sensibility remained, finding new ways to surface.

In Cuba, this resistance took on spiritual dimensions. African religions were forced underground, masked behind Catholic iconography. Orishas were renamed as saints. Ceremonies were hidden in plain sight. Batá drumming, deeply sacred and African, continued under the watchful eyes of colonial power. Over time, what was once purely ritual began to bleed into the secular world. Rumba emerged. Social drumming took shape. The line between the sacred and the everyday blurred, but the African heartbeat never left. What followed in the Caribbean was more collision. Africa met Europe, and both met the Indigenous peoples of the islands. This was but a collaboration that was forged under violence—but culture, stubborn and adaptive, found a way forward. African percussion formed the base. Spanish colonizers contributed harmonic structures, string instruments, and poetic forms. And then there were the Taíno, often written out of history, whose instruments, the güiro and maracas—added texture and sharpness to the sound. Their presence lingers in every scrape and shake. Out of this collision came Son Cubano. In many ways, Son is the DNA of Salsa. African rhythm carried Spanish melody, grounded by Indigenous instrumentation. It was rural, communal, and portable. It belonged to the people, not the elite. And for a time, it traveled freely, moving from Cuba to New York, from Havana to Harlem, shaping and being shaped by jazz musicians, dancers, and migrants chasing possibility.

Then politics intervened, the Cuban Revolution and the subsequent U.S. embargo severed a cultural artery. Records stopped arriving. Musicians stopped traveling. The constant dialogue between Cuba and New York was abruptly cut, what’s fascinating is what happened next. In Cuba, music evolved inward, becoming more technical, more complex, more insulated. In New York, absence created urgency. Puerto Ricans, Dominicans, and African Americans inherited an older tradition and were forced to make it speak to their reality.

This is where Salsa truly crystallized. In the barrios of New York, the music absorbed the pressure of city life—the poverty, the racial tension, the pride, the anger, the joy. It learned from jazz. It borrowed from soul. It reflected the sound of sirens, crowded apartments, and survival in a city that often had no room for Black and Brown bodies. So when the term “Salsa” was popularized, it wasn’t just a branding decision; it was a declaration. This music was plural. Mixed. Spicy. Impossible to reduce to one nation or one story. And the stories it told were no longer abstract. They were deeply personal. They spoke of displacement, of identity, of being Afro-Latino in a country that rarely made space for complexity. Artists like Celia Cruz, Héctor Lavoe, Eddie Palmieri, and Johnny Pacheco testified to this with their music, their art carried humor, heartbreak, spirituality and street-level realism. It made people dance, yes, but it also made them feel seen.

Listening to Salsa closely, you begin to hear layers speaking to each other across centuries. The conga echoes Central Africa. The clave remembers Yoruba cosmology. The güiro whispers Taíno survival. The horn sections reflect Black American jazz traditions shaped in Harlem and beyond. Nothing in Salsa exists in isolation. Every sound is an inheritance. That is why Salsa belongs firmly within Black history. Not as a footnote or as a “Latin” aside, but as a living archive of the African diaspora. It reminds us that culture does not disappear when borders close or when names change. It mutates, adapts and often finds new homes in new cities and speaks in new accents.

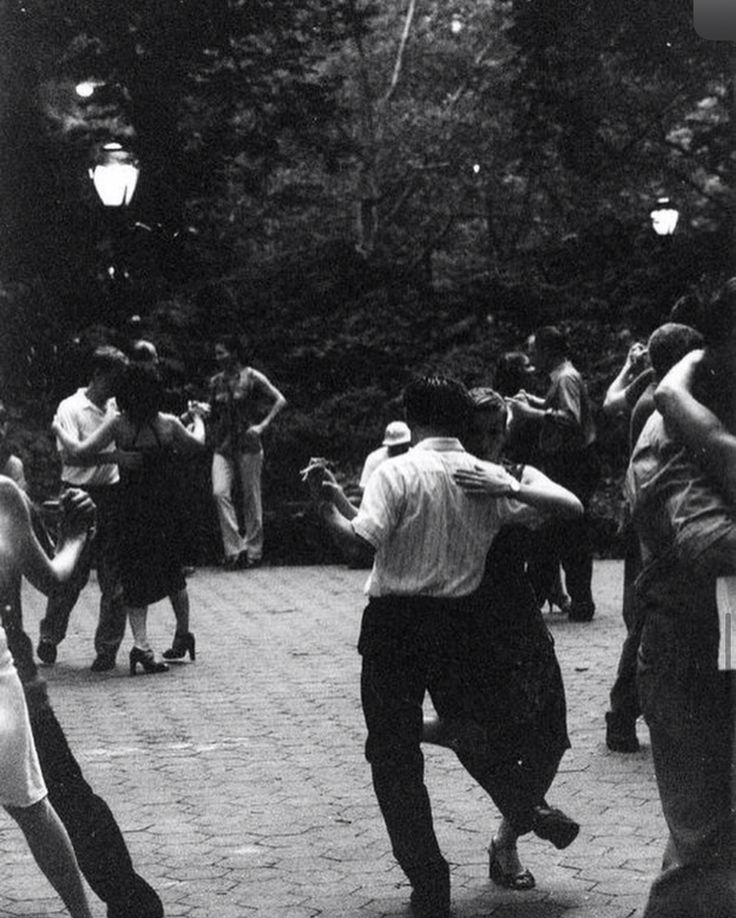

What we call Salsa today is really a long conversation between generations who were denied the right to speak freely, yet found ways to talk through sound. This is why it refuses to sit still in one place or belong to one flag. It is African without being frozen in Africa. Caribbean without being contained by the islands. American without surrendering its soul. It exists in motion, the same way the diaspora does—constantly negotiating identity, carrying fragments of home, inventing new ones along the way. Salsa endures because the people who created it endured. And as long as the rhythm continues, on dance floors, in barrios, in living rooms, and in new cities yet to claim it—the story of Black survival will keep finding new ways to be heard.