The banjo, often seen today as a symbol of American folk and bluegrass music and a symbol of white Appalachian culture, has roots that run much deeper—a darker truth to its popularity.

The banjo is not originally American, nor white. It is African, culturally, historically, and spiritually—an instrument born of African heritage, carried across the Atlantic by enslaved Africans and reimagined in the brutal context of bondage.

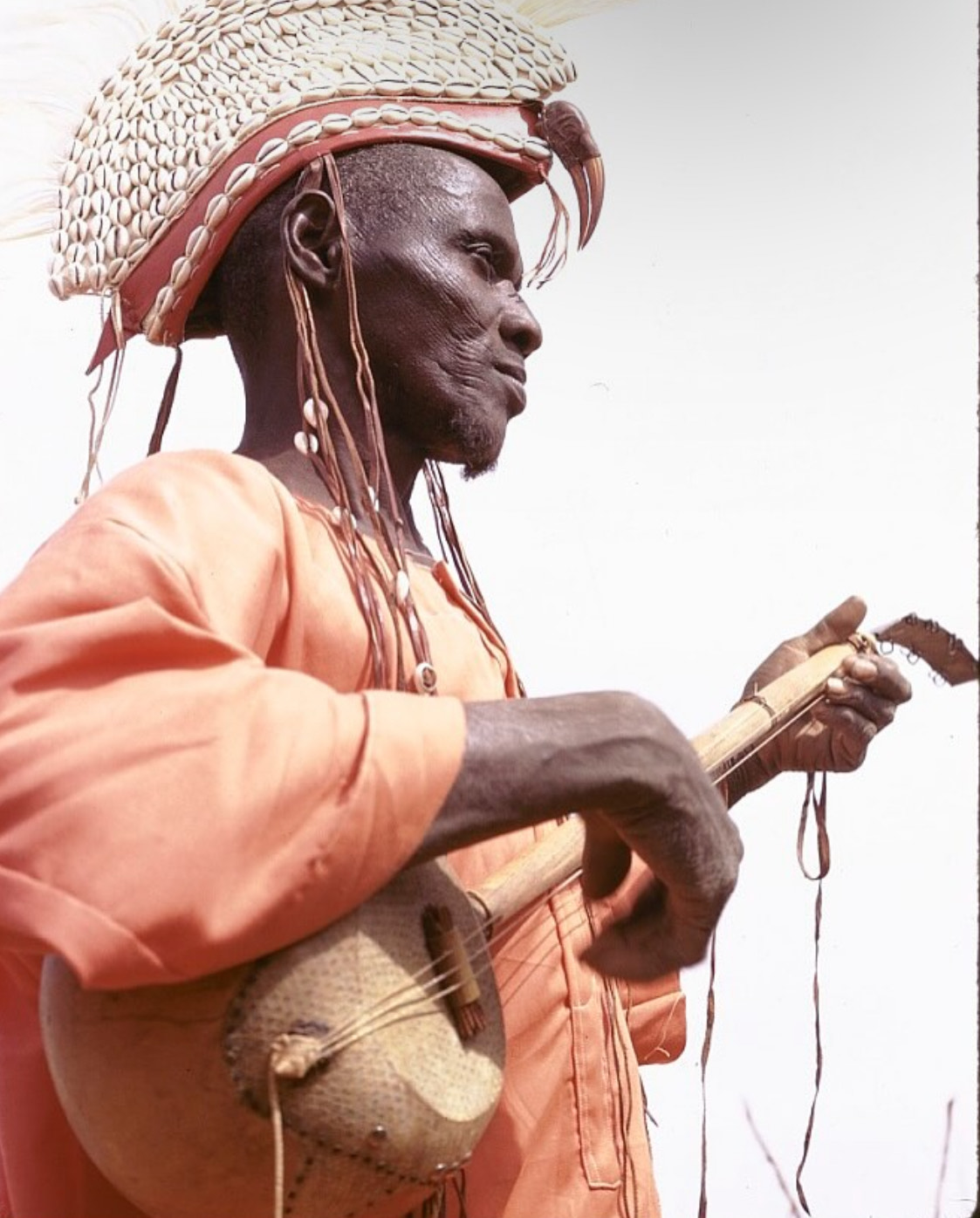

Long before the banjo was romanticized on front porches in the American South, its ancestors were played across West Africa. Similar stringed instruments like the akonting (Senegal and Gambia), ngoni (Mali), and xalam were already part of centuries-old musical traditions. They served as vehicles for storytelling, oral history, and spiritual practice.

These instruments shared key structural features with the modern banjo: a skin-covered resonator body (often a gourd), a long fretless neck, and strings plucked by hand.

When millions of Africans were enslaved and forcibly transported to the Americas during the transatlantic slave trade, they brought these musical traditions with them—sometimes literally, in the form of handmade instruments crafted in captivity. The earliest references to banjo-like instruments in the New World appear in the Caribbean in the 17th century, where enslaved Africans built them from local materials and used them in cultural and spiritual ceremonies.

By the 18th century, the early form of the banjo was being played on plantations across the American South. But as minstrel shows gained popularity in the 19th century, white performers began to mimic Black musicians in racist blackface performances, adopting and adapting the banjo along the way. Through these actions, the banjo was stripped of its African identity and repackaged as a symbol of rural white Americana.

The instrument that had once carried the cultural memory and resilience of enslaved Africans was now used to reinforce harmful stereotypes and entertainment that mocked the very people who had created it. Over time, the banjo was refined and commercialized by white musicians and instrument makers. Black contributions to this music were systematically ignored, if not actively erased, in both academia and the music industry. The irony is sharp: a genre built around an African instrument was now being used to define a falsely whitewashed national identity.

Meanwhile, Black banjo players were largely pushed to the margins. Though artists like Uncle John Scruggs, Gus Cannon, and Dock Boggs maintained Black traditions of banjo playing, their recognition remained limited. It wasn’t until late in the 20th century that scholars and musicians began to revisit the true origins of the instrument. Today, artists like Rhiannon Giddens, Dom Flemons, and Allison Russell are part of a growing movement to reclaim the banjo’s African identity and reinsert Black narratives into the folk canon.

Understanding the banjo’s true history goes beyond musicology—it’s a matter of cultural justice. Originally a symbol of resilience within West African traditions, the banjo was appropriated and transformed into a staple of white Americana, reflecting a broader pattern of cultural theft in American art.

Reclaiming its legacy means acknowledging this painful past while uplifting the Black artists who continue to redefine its sound. Far from being just a stringed instrument, the banjo stands as a resonant artifact of stolen culture and a reminder that the roots of American creativity are deeply entwined with the struggles and brilliance of the African diaspora.

.svg)

.png)