D’Angelo’s passing moved the world to a resounding, harrowing halt. Our collective devastation and utmost admiration spoke to his immeasurable impact on Black soul, funk, and R&B music since 1994.

The genesis of his sound heavily derives from the Black church– a foundational element of American music across countless genres. From the energy of the choir: the altos, sopranos, and tenors in joint harmony, the commanding power of the guitar’s grounding bassline, to the enigmatic, cinematic control the organ demands—these elements were all intrinsic to D’Angelo’s musical journey.

“This is a very powerful medium that we are involved in,” D’Angelo told GQ in 2014. “I learned at an early age that what we were doing in the choir was just as important as the preacher. It was a ministry in itself. We could stir the pot, you know? The stage is our pulpit, and you can use all of that energy and that music and the lights and the colors and the sound. But you know, you’ve got to be careful.”

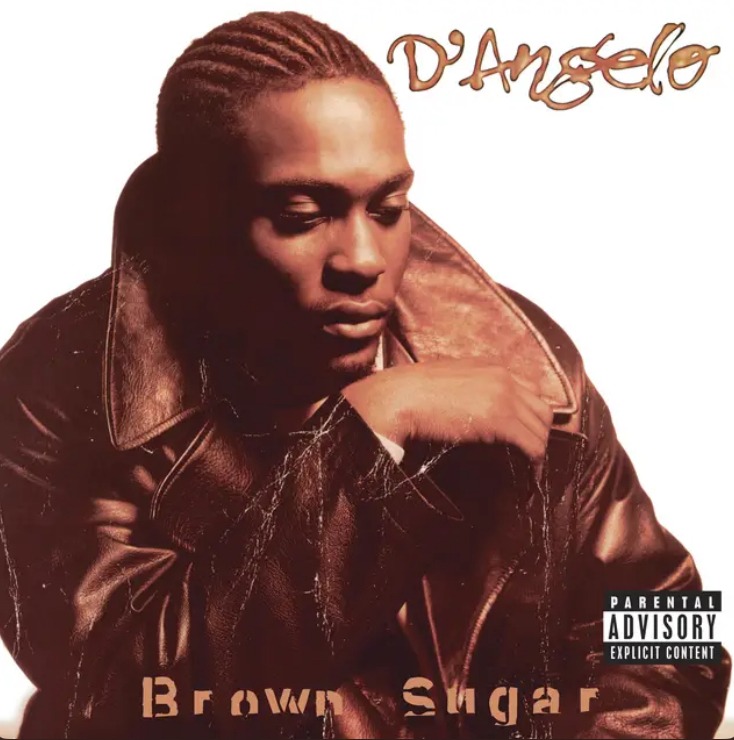

Virginia-born Michael Eugene Archer, also known as D’Angelo, reshaped the entire sonic landscape of R&B. Utilizing vintage instruments like Wurlitzer and dated effect boxes, he fused laid-back soul with a new stylized funk-jazz-pop-afro sound in ‘Brown Sugar,’ his 1995 debut album. Though producer Keda Massenburg coined the phrase ‘neo-soul’ and recognized D’Angelo as the pioneer of the ‘neo-soul’ subgenre, D’Angelo rejected this, and in an interview with Red Bull Music Academy, he stated: “I never claimed I do neo-soul…When I first came out, I used to always say, ‘I do black music. I make black music.’”

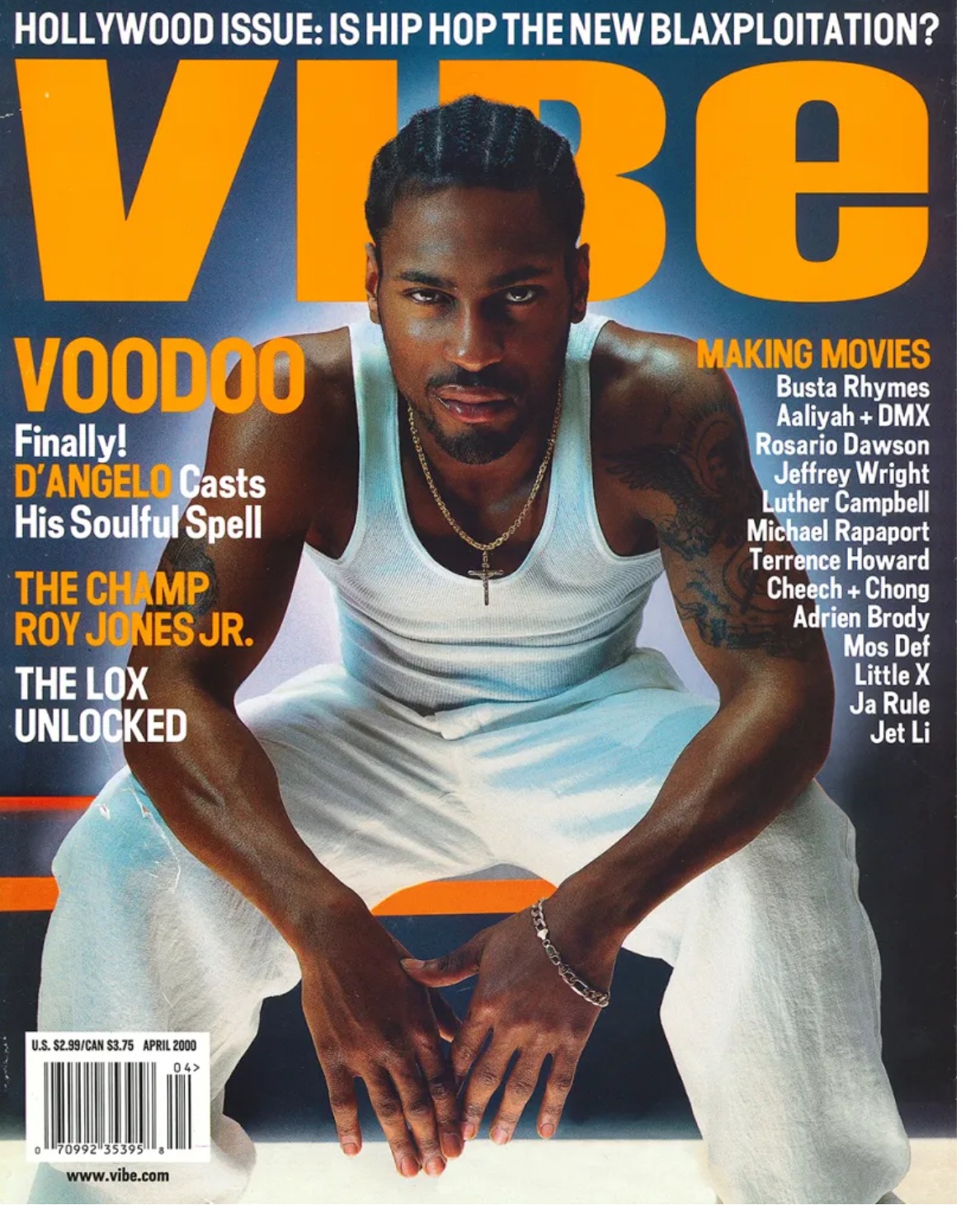

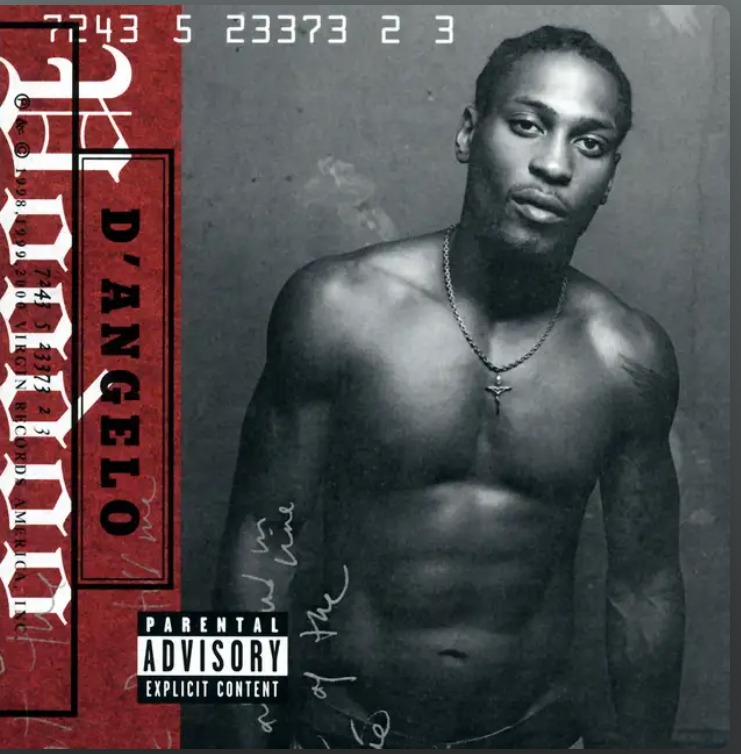

Refusing to limit his musicality, he was endlessly inspired across the African diaspora, most notably in his 2000 sophomore album ‘Voodoo.’ Winning the Best R&B album Grammy for that year, debuting at number one on the Billboard 200’s chart, and selling 320,000 copies in its first week, this album was a critical success that fused afro-caribbean, funk, hip-hop, salsa, blues, neo-soul, gospel, and jazz all in one. The final single, ‘Untitled (How Does It Feel)’ was ranked by Rolling Stone as one of the Greatest Songs of All Time.

“HOW DOES IT FEEL? / (Wanna know how it feels, yeah)

HOW DOES IT FEEL? / (Said did it ever cross your mind?).”

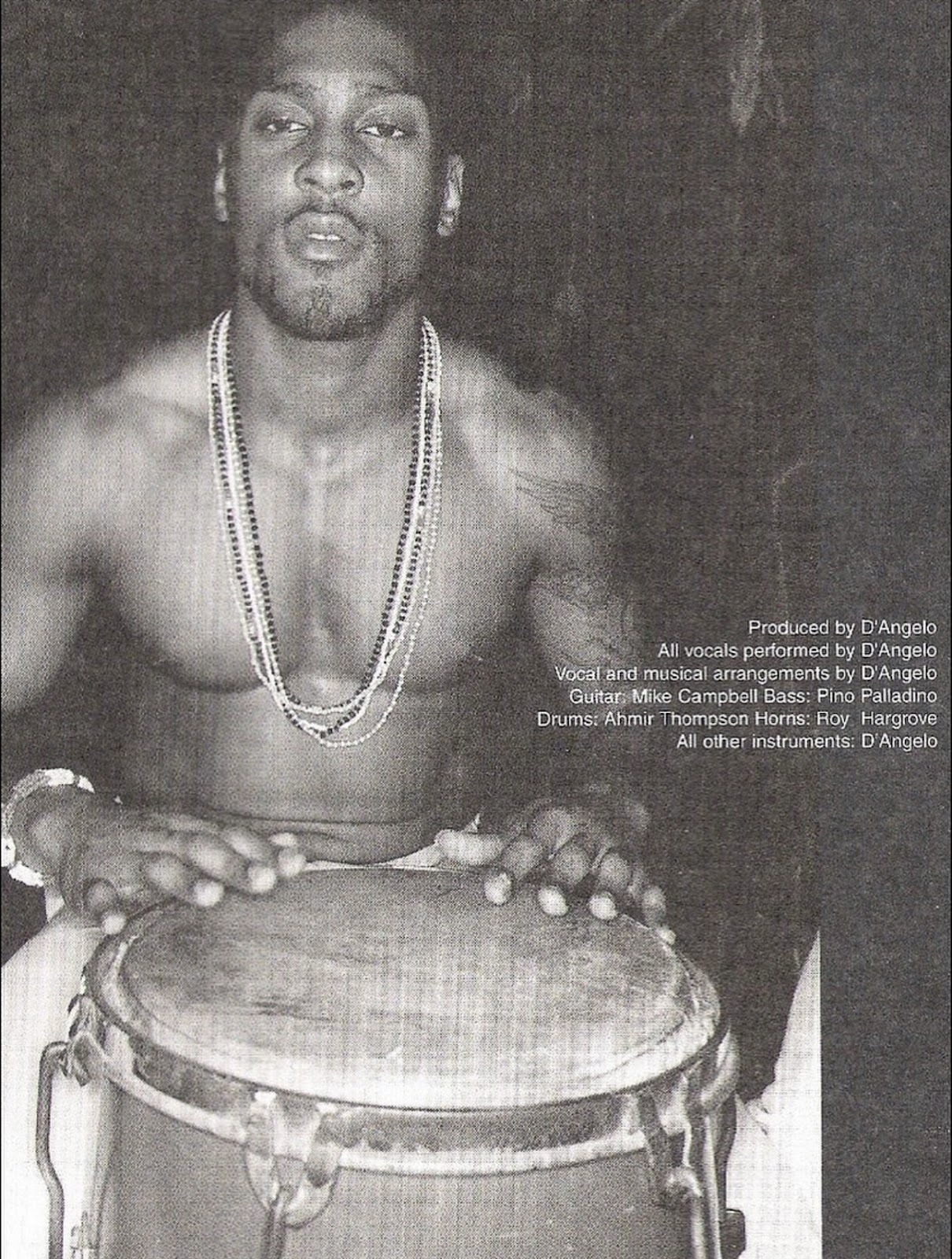

D’Angelo’s vision for this album was heavily influenced by African traditions. The last song on the album, named ‘Africa’, layers smooth gospel chords and subtle echoing harmonies, alongside gorgeous ad-libs–culminating in a meditative ode to belonging, home, and being Black between two opposing worlds.

“Africa is my descent / And here I am, far from home / I dwell within a land that is meant for many men not my tone, yeah / The blood of God is my defense / Let it drop down to my seed / Showers to your innocence / To protect you for all eternity / And with this wood, I beat this drum / We won't see defeat, yeah / From kings to queens becomes a prince / Knowledge and wisdom is understanding what we need.”

With regards to the title ‘Voodoo’, in an interview with Jet Magazine, he spoke more to its influence, noting: “I named the album Voodoo because I really was trying to give a notion to how powerful music is and how we as artists, when we cross over, need to respect the power of music. Voodoo is ancient African tradition. We use ‘voodoo’ in the drums or whatever, the cadences and call-out to our ancestors and that in itself will invoke spirits. And music has the power to do that, to evoke emotions, evoke spirit. That’s something I learned in the church when I was very young and that’s what I wanted to get across.”

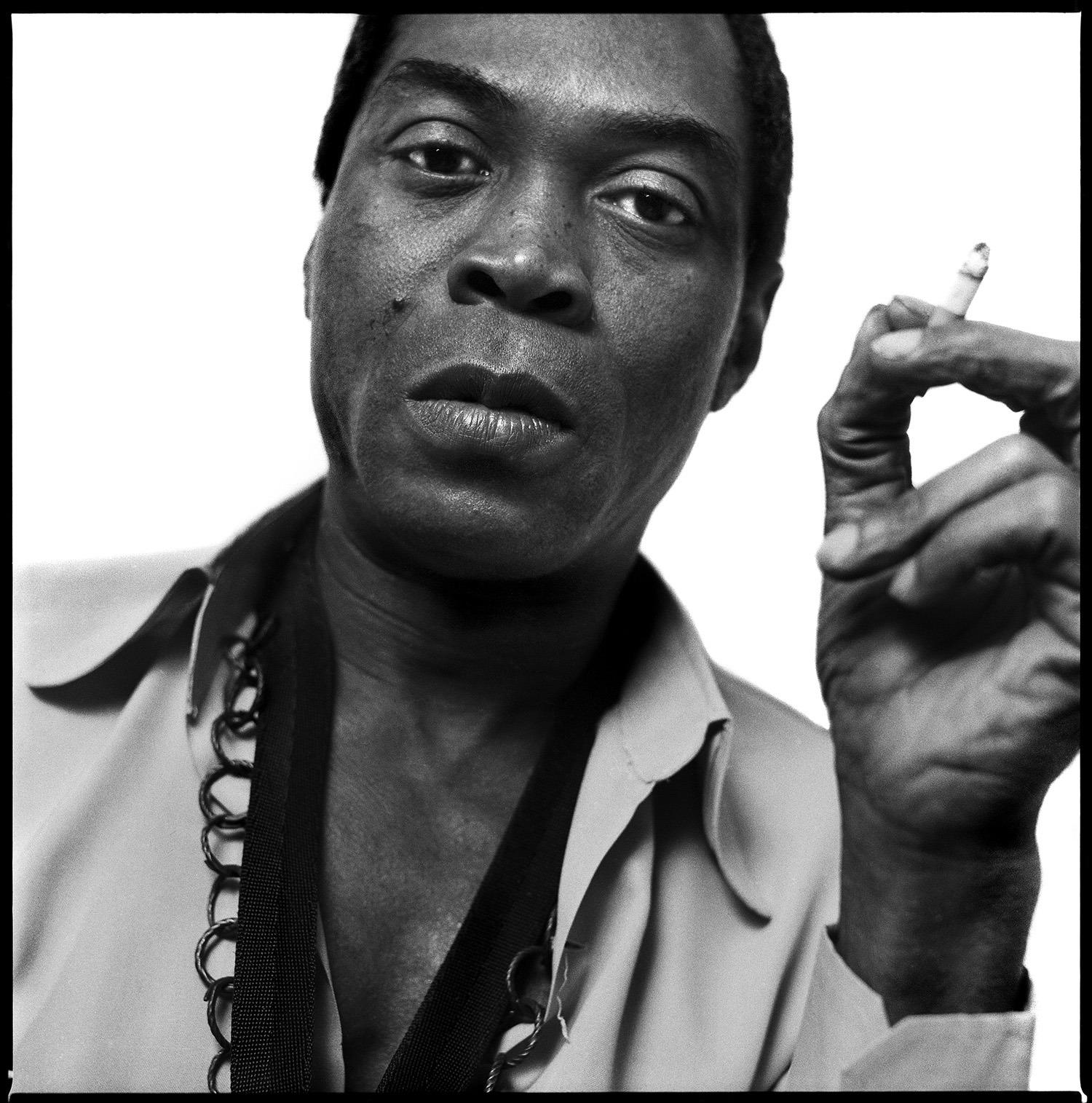

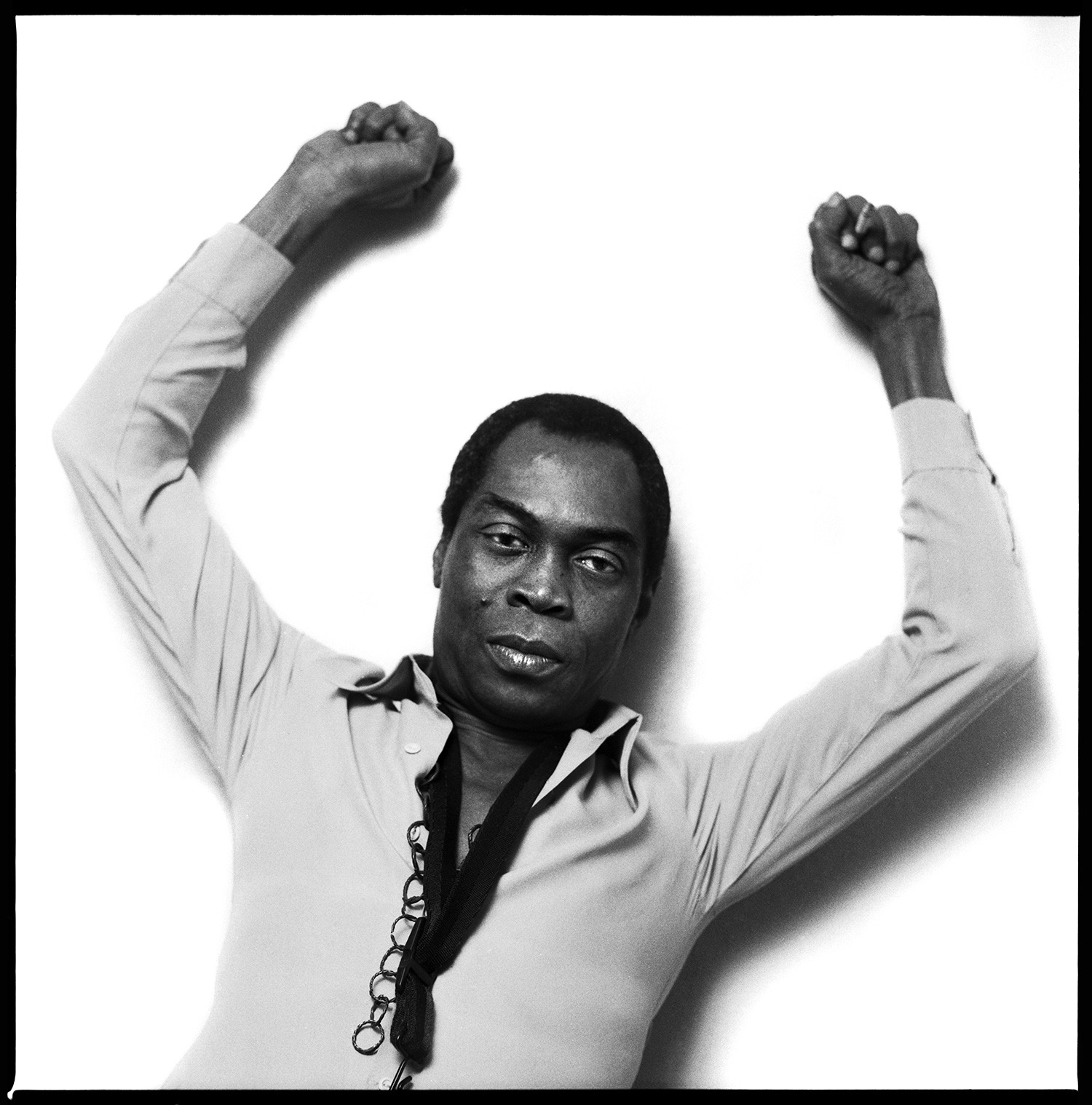

Building on this, D’Angelo was increasingly fascinated by the work of Olufela Olusegun Oludotun Ransome-Kuti, most commonly known as Fela Kuti. Hailing from Abeokuta, Nigeria, band-leader, activist, producer, and multi-instrumentalist Fela Kuti was committed to advocating against the regressive systems in Nigeria and speaking out for the poor. This guided his lyricism and the way in which he approached the stage. Fusing social commentary with his politically charged lyricism, he layered horn arrangements, jazz undertones, and traditional highlife with raw guitars alongside his extensive 20-member band. He is credited as a major fixture in the creation of the Afrobeat genre, a fusion of traditional highlife with jazz and funk.

‘Water No Get Enemy’ was released in 1975 on his ‘Expensive Shit’ album, an almost 10-minute track that takes listeners on a dynamic journey from start to finish. Opening with punchy staccato horn phrasing, jazzy chords, brilliant guitar riffs, and smooth saxophone solos, Fela’s band spends nearly half the song in an almost unscripted jam session, an intricate lineup of percussion, horns, guitars, and keys. Halfway through, Fela begins singing in Yoruba and pidgin English, expounding on the Yoruba proverb on the importance of water in both the literal and conceptual sense— tying Black resistance to the unshakeable, immutable force of water:

“T'o ba fe lo we omi l'o ma'lo / If you want go wash, a water you go use / T'o ba fe se'be omi l'o ma'lo / If you want cook soup, a water you go use / ri ba n'gbona o omi l'ero re

If your head dey hot, a water go cool on / T'omo ba n'dagba omi l'o ma'lo / If your child dey grow, a water he go use / I dey talk of Black man power (Water, him no get enemy!) / I dey talk of Black power, I say (Water, him no get enemy!) / I say water no get enemy (Water, him no get enemy!)”

25 years later, D’Angelo takes this track, flips it on its head to add a gospel, funk, electric, R&B twist. Recorded for the Red Hot + Riot compilation at the iconic Electric Lady Studios in New York City, D’Angelo, Femi Kuti, Macy Gray, Roy Hargrove, Nile Rodgers, Positive Force, Roy Hargrove, and The Soultronics join forces with producer Questlove to craft a legendary cover of Fela’s well-renowned song. As Questlove counts down, Femi Kuti opens with an electrifying saxophone solo, alongside Nile Rodgers' enticing guitar solo. The beautiful vocal interplay between D’Angelo’s soulful adlibs, Macy Gray’s raspy, jazzy inflections, and Femi Kuti’s powerful Yoruba chants blends seamlessly in this eccentric take on Fela’s original record. The spirit of D’Angelo’s funk and gospel sensibility is heavily prevalent here, honoring the arrangement of the original song while also crafting, building, and experimenting with something so intricately, brilliantly, and innately new.

(D'Angelo)

(Oh, oh, yeah...)

(Oh yeah... oh yeah... mmm, mm-mm, yeah...)

(Femi Kuti, Macy Gray and (D'Angelo)

T′o ba fe lo we omi l'o ma′lo, oh-ohh / If you want go wash, a water you go use (Ah, ah)

T'o ba fe se'be omi l′o ma′lo, oh-ohh / If you want cook soup, a water you go use

T'o ri ba n′gbona o omi l'ero re / (If your head get hot, water you gon' use – ah, ah)

T′omo ba n'dagba omi l′o ma'lo / If your child dey grow, now water you go use / T'omi ba p′omo e o omi na lo ma′lo – you don't want that now / If your child dey grow, now water you gon' use / (And you don't want that, you don't want that, no...)

D’Angelo and Fela Kuti both understood the power of music as a vessel to communicate stories of vulnerability, love, oppression, Black spirituality, and community. The mark of a great artist is the ability to see music beyond themselves. It was never only about the individual, but rather a portal to the boundless power within the communal African diasporic tradition— encompassing gospel, funk, soul, R&B, highlife, afrobeat, jazz—and the innumerable future genres that have yet to be fully realized.

D’Angelo’s ‘Water No Get Enemy’ functions not only as an aesthetic homage, but a bridge connecting 1970s African political resistance to early 2000s meditations on Black spirituality, belonging, and culture.