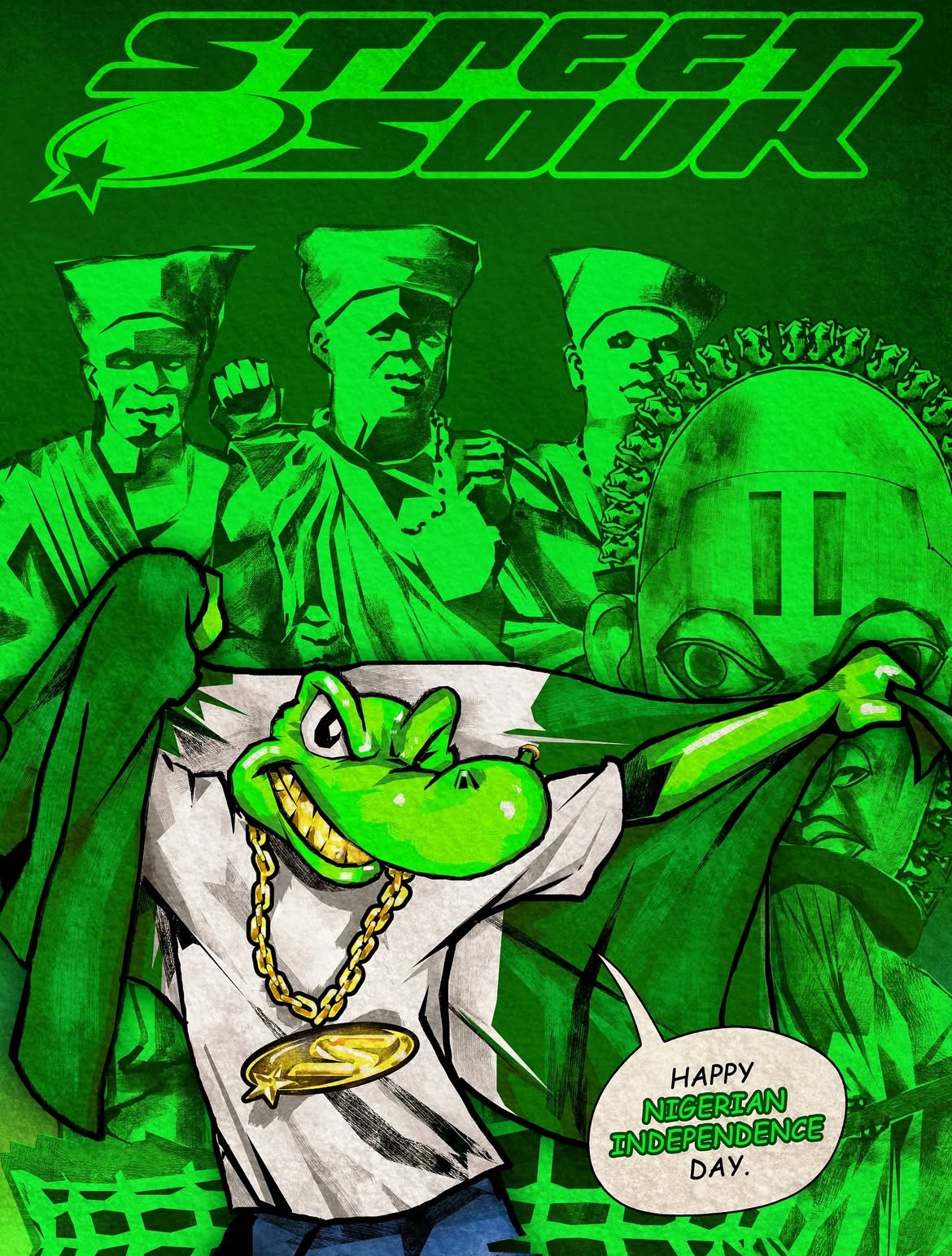

This year at Lagos Fashion Week, something unusual happened. For the first time in a long time, streetwear, the lifeblood of African youth culture, made a formal appearance on the runway. The moment came courtesy of Street Souk, Nigeria’s leading streetwear convention founded by Iretidayo Zaccheaus. A welcome sight, yes. But the showing left many wondering if the inclusion was merely symbolic rather than systemic.

Street Souk’s presence felt both progressive and performative. While it signaled a recognition of streetwear’s influence, it also underscored how little space the movement truly occupies on Lagos Fashion Week’s main stage. The irony? Streetwear is arguably the most vibrant and globally relevant form of African fashion today. From the oversized tees and baggy denim flooding Lagos streets to the expressive, gender-fluid fits worn by alté kids across the continent, this is what African style looks like now. Yet, on the official runway, the supposed mirror of the culture, it’s almost invisible.

So, why is African streetwear still fighting for a seat at the table?

Lagos Fashion Week (LAFW) was built on a high-fashion framework modeled after Paris, Milan, and London. It prioritizes luxury, structure, and seasonal collections, systems that don’t align with how streetwear functions. Streetwear thrives on spontaneity: drops, pop-ups, collabs, and cultural moments. Its success is built on community, not couture.

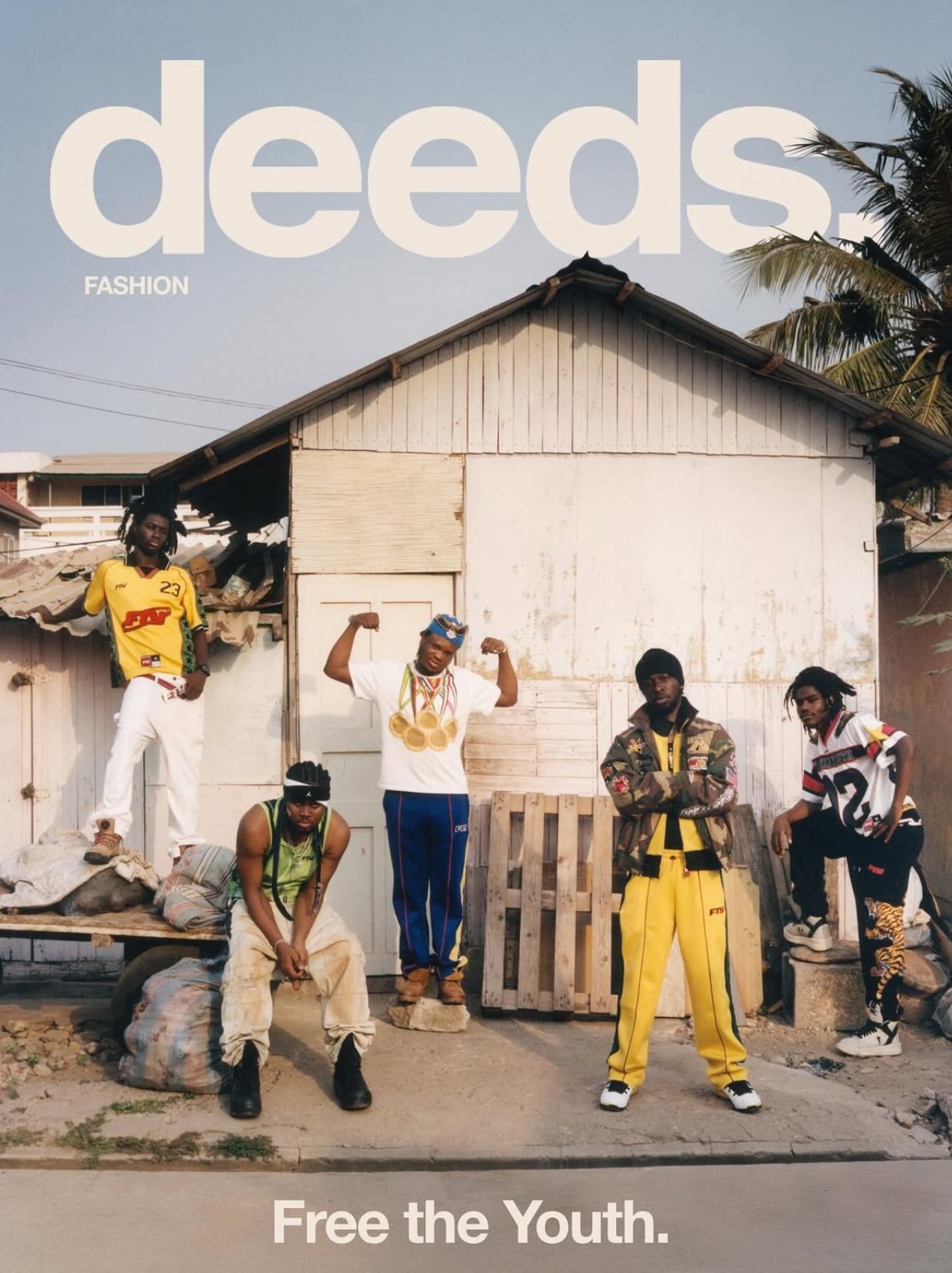

This structural disconnect makes it difficult for LAFW to accurately reflect what’s happening on the ground. When the event does engage with streetwear, it often treats it as a novelty or side attraction rather than a legitimate design movement. Including Street Souk as a collective was a good start, but it also blurred individual designers into one amorphous brand. The result? The people driving the culture, designers like Free the Youth, Motherlan, WAF, and Severe Nature amongst others remain faceless in the grand narrative.

Then, there’s money— the great divider in Nigerian fashion.

To show at Lagos Fashion Week, designers reportedly pay a participation fee of around ₦179,880 (about $120 USD). But that’s just the entry point. The real costs lie in production, creating a runway-ready collection, paying models, styling, lighting, hair, makeup, PR, and logistics. According to Vogue Business, most emerging brands spend between ₦2 million to ₦5 million (roughly $1,300–$3,200) to participate fully in Fashion Week, factoring in materials and presentation. For context, some established Nigerian designers spend over ₦83 million (above $57,000) for international showcases.

Streetwear labels, most of which are youth-led and self-funded, simply can’t compete on that scale. Many rely on personal savings, side hustles, or crowdfunding to produce their collections. Their ecosystem is built on efficiency and digital accessibility, not capital-intensive runway formats. That’s why streetwear thrives in spaces like Street Souk and Homecoming Festival, where the cost of entry is low and the energy feels authentic.

The LAFW structure, as it stands, favors institutionalized brands and designers with corporate sponsorship. For the rest, the dream of showing on that glossy runway is as distant as Paris itself.

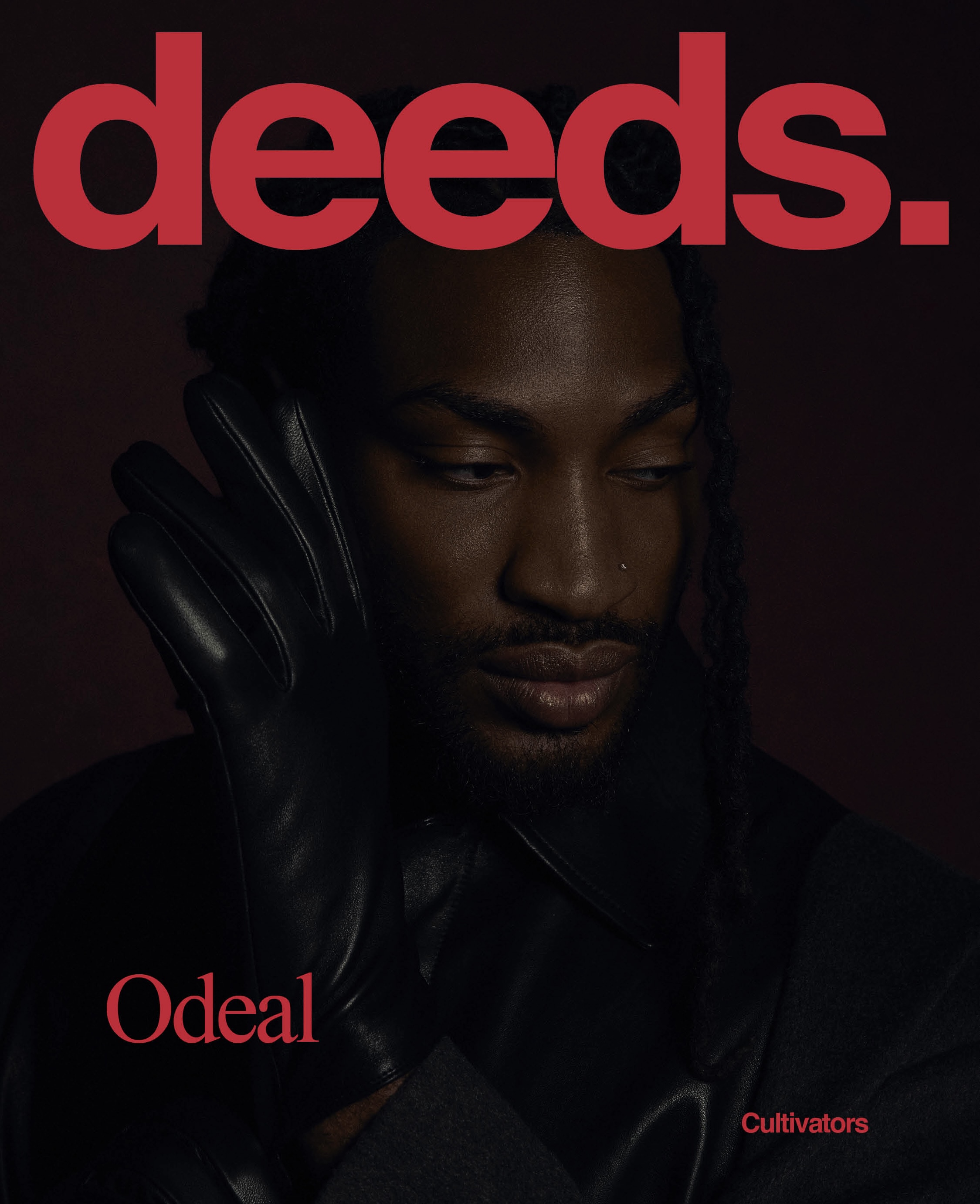

Beneath the economics lies another issue: gatekeeping. For years, Nigeria’s fashion establishment has been slow to embrace the creative energy of Gen Z. The industry’s gatekeepers such as stylists, editors, and curators still define “fashion” through Eurocentric parameters. A deconstructed tracksuit or hand-dyed cargo pants might not fit their idea of couture, even though that’s exactly what the next generation is wearing.

Streetwear isn’t just clothes but also it’s language, rebellion, and cultural memory. It draws from markets, bus stops, and backstreets, translating everyday survival into fashion. Yet, when institutions filter this through polished runways, it risks becoming sanitized, a digestible version of rebellion. This isn’t inclusion; it’s gentrification.

Streetwear doesn’t need the runway to exist. It lives in Lagos’ thrift markets, on Instagram pages, at underground shows, and in studio photoshoots. It lives in the self-expression of young Nigerians who remix old school Nollywood, global hip-hop, and Yoruba slang into something entirely their own.

Events like Street Souk and Homecoming have built ecosystems where music, art, and fashion collide without institutional validation. Here, designers trade ideas directly with consumers. The runway is the street itself—unfiltered, messy, and alive.

But fashion weeks are meant to document and elevate what’s real. If they continue to overlook the rawness of African youth culture, they risk losing relevance altogether.

Street Souk’s involvement at LAFW was a breakthrough, but it also highlighted the flaws in the system. The collective format allowed for cultural representation, but it diluted individuality. Viewers saw “Street Souk,” not the brands within it. The narrative became one of inclusion rather than equity, a seat at the table, but not a voice in the room.

The danger is that when institutions adopt streetwear as an aesthetic trend, they often strip it of its community-driven roots. What was once an act of rebellion becomes a fashion statement. The culture gets co-opted, and the creators fade into the background.

For Lagos Fashion Week to truly represent the pulse of African fashion, it must evolve beyond symbolic gestures. Inclusion should be structural, not seasonal.

It could start by:

Creating subsidized slots or youth-led showcases for streetwear designers.

Reimagining presentation formats: street shows, pop-up runways, digital storytelling that reflect how this generation designs and consumes fashion.

Highlighting individual designers from collectives like Street Souk, not just the platform.

Encouraging collaborations between established fashion houses and streetwear labels to build bridges across creative generations.

African fashion is no longer confined to couture silhouettes and traditional prints. It’s in the sneakers, the thrifted cargo pants, the airbrushed tees, and the slang-stitched hoodies. Streetwear is not a subculture, it’s the culture.

As Lagos Fashion Week continues to evolve, the real opportunity lies in shifting from showcasing fashion about Lagos to presenting fashion from the streets of the city and next year could be the turning point.

.svg)

.png)

.png)