Nigerian fashion photography never announced itself. Archival fashion images existed because people dressed, gathered, moved through public life, and someone, somewhere, raised a camera. Fashion entered the image sideways. It was not always the subject, but it was always present. These images travelled unevenly. They were preserved selectively and disappeared often. To look back at this visual history is not to trace a neat lineage of style, but to confront a question of visibility: who was seen, who was remembered, and who never entered the frame at all.

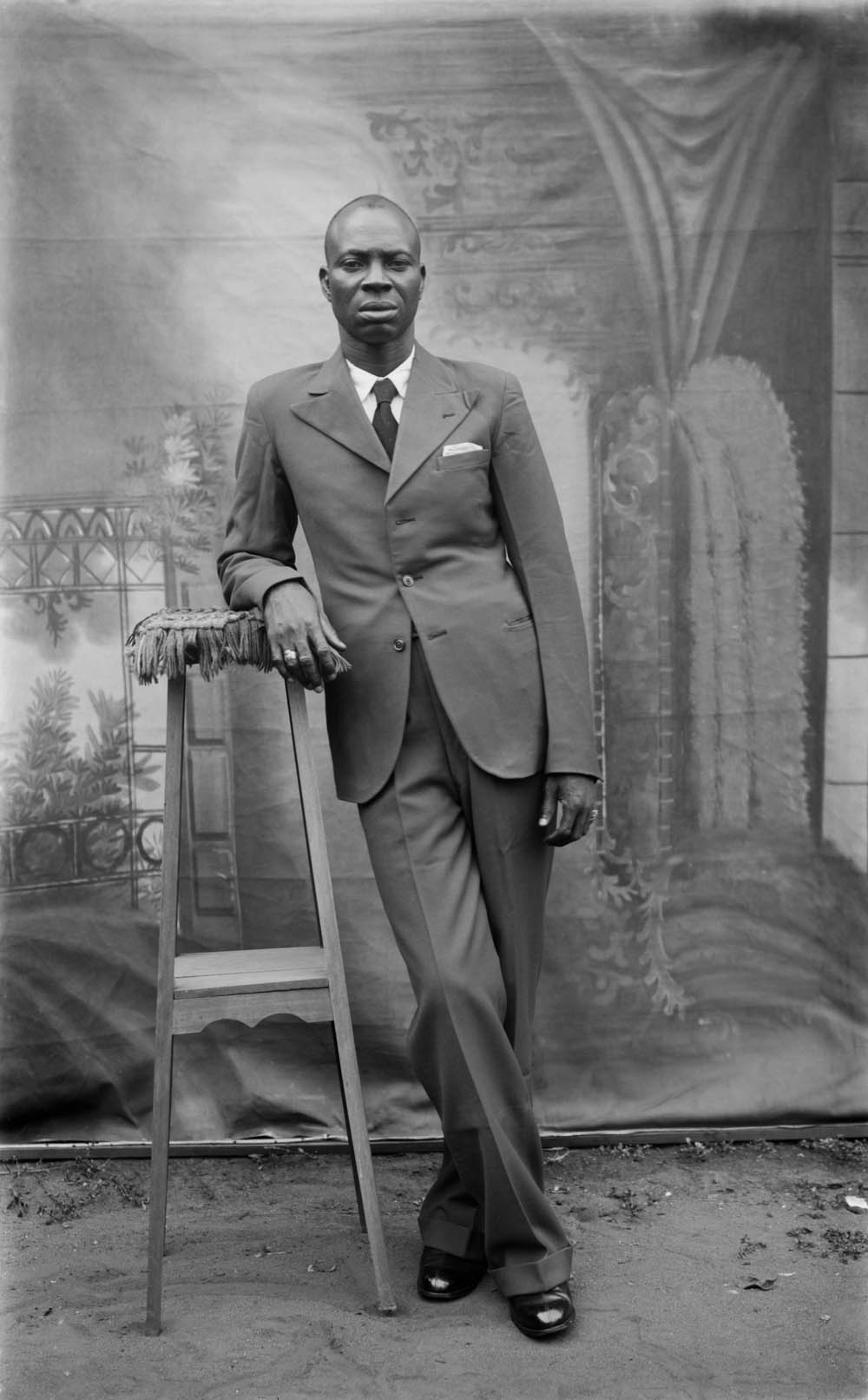

Formal studio portraiture shaped some of the earliest fashion images in post-independence Nigeria. In the decades following independence, portrait studios across Lagos, Ibadan, Onitsha, Aba and Benin City offered something precise: proof of presence. To be photographed was to mark a moment — new clothes, new income, a changing self — within a society moving quickly. These images were not made as fashion statements, however fashion was central to them. Select clothing signalled aspiration and status. The camera rewarded those who could afford time, stillness and film, and what it captured became history by default.

Fashion imagery in Nigeria has never been neutral. It has always been shaped by access (to studios, to technology, to circulation) and by the power to be documented at all. The archive, as it exists today, reflects these conditions. It holds certain faces with clarity, and it holds gaps just as clearly.

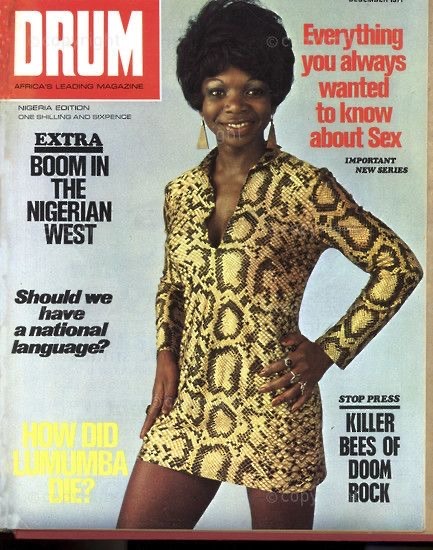

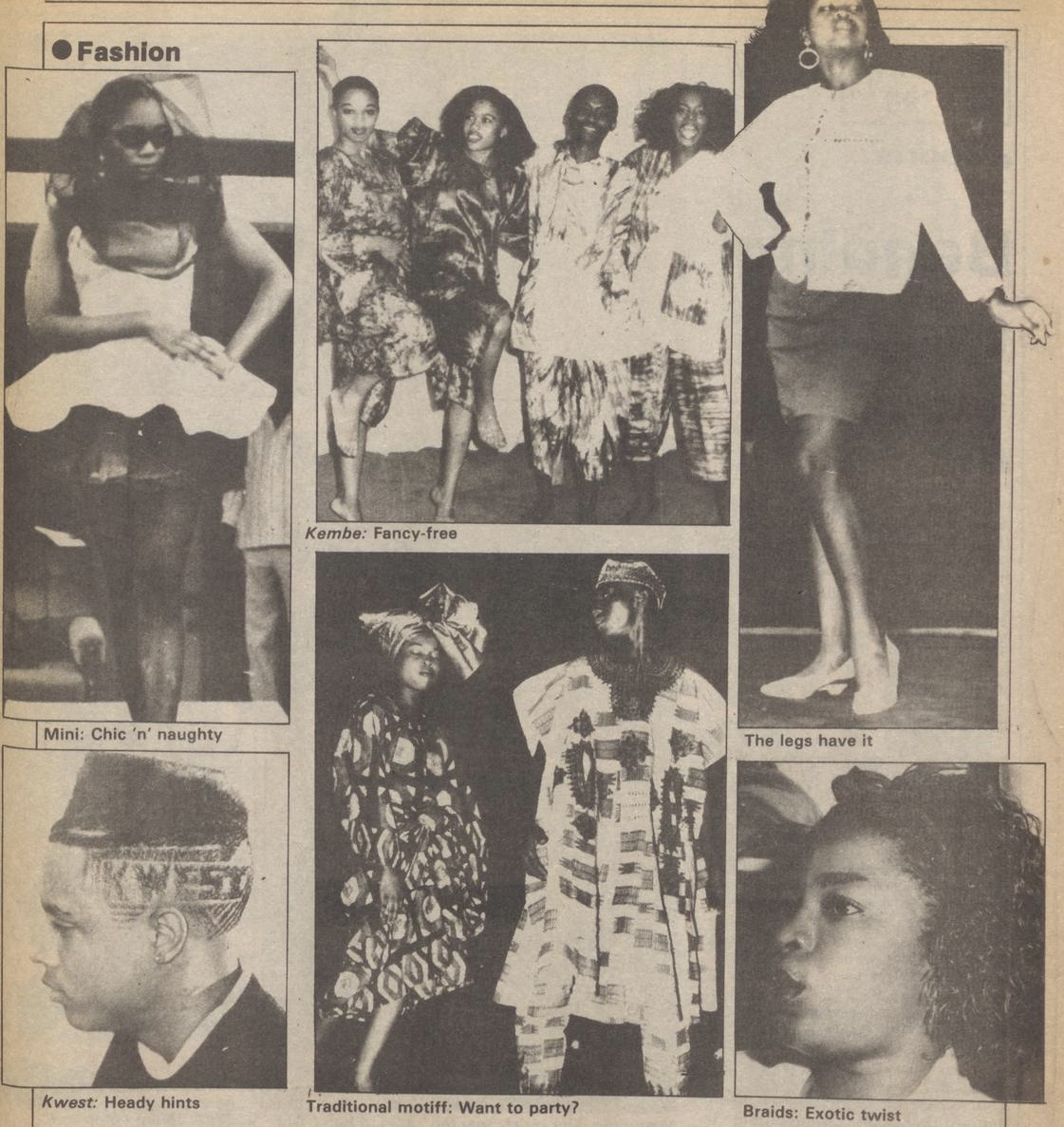

By the late 1970s to 1990s, fashion photography entered print culture more decisively. Newspapers and magazines such as DRUM, West African Pilot and Rave introduced dedicated fashion pages, positioning style as part of public discourse. These images shaped taste and aspiration, and desirability, giving Nigerian fashion an editorial language.

However, editorial visibility came with its own further exclusions. Socialites, celebrities and elite figures dominated the frame. Their bodies and wardrobes came to stand in for Nigerian fashion at large. Designers working informally, street vendors shaping trends, and everyday wearers seemed to rarely appear. When they did, their names were often omitted and contexts were left unrecorded. As this visibility narrowed, Nigerian fashion was documented selectively.

By the late 1990s and early 2000s, before social media imposed scale and permanence, much of Nigerian fashion culture circulated without consistent documentation. Style moved through repetition and proximity: parties, music videos, nightclubs, word of mouth. Being seen mattered more than being captured. Photographs existed, but they were not consistently preserved. Many were taken on personal cameras or through informal shoots by undocumented photographers, remaining in private collections or disappearing altogether over time. Much of this visual culture survives mostly through recollection: who wore what, where it was seen, why it mattered. This period reminds us that fashion does not require visibility to exist. It does, however, require visibility to enter the archive.

The Archive as Gap

When Digital archivist and image maker Daniel Obaweya, known as Nigerian Gothic, talks about Nigerian archival fashion photography, he doesn’t begin with completeness. He begins with what’s missing. “My introduction to fashion history came from a loss of image,” he says, describing an archive that revealed itself not through abundance, but through absence.

It’s evident that to study Nigerian fashion photography is to confront what never made it into the frame, because not every look was photographed, not every photograph was kept, and not every face was considered worth preserving. What remains is uneven and shaped as much by loss as by presence.

A lot of Nigerian fashion imagery was never produced with permanence in mind. Studio portraits from the 1960s and 70s were often taken for personal reasons, not public record. “Sometimes it’s just people coming into studios to get pictures,” Obaweya explains. “It’s not like they were using it for anything. It was just for the memory of it.” These images were intimate, domestic and unassuming.

But memory is fragile. Nigeria lacks the infrastructure that allows images to endure. “We don’t have a library culture,” Obaweya says plainly. Decades of limited public investment, inconsistent policy frameworks and the absence of functioning public archival institutions have left photographic histories exposed. Even large-scale, privately funded preservation attempts reveal how precarious the ecosystem remains. Years of planning and significant expenditure can still be destabilised by weak governance, contested authority, or the absence of protective systems around cultural work, take MOWAA as an example.

Much of what survives today does so by chance rather than care, because someone stumbled across an image, not because it was systematically protected. This unevenness shapes whose faces remain visible. The archive, as it exists now, privileges those who had access to studios, film, storage and print circulation. Others slip out of view. “A lot of the images we’ve been able to see are because international people found these photographers and did the research,” Obaweya notes. When visibility arrives through external discovery, what does that mean for how Nigerian fashion history is framed, and who gets to decide what is worth remembering?

Yet fashion photography, for Obaweya, remains one of the clearest ways to read social history. “You can use fashion or visual culture, photography… to understand the times better,” he says. Political shifts, labour conditions, economic change — all of it appears on the body. What people wore, how they posed, and where they stood are records of lived conditions.

What remains unresolved is not only what is missing, but what that absence teaches us. Which faces were never photographed? Which images were never kept? And how do we read a history shaped as much by disappearance as by survival?

Today, images circulate faster than ever, but visibility remains concentrated. Attention gathers around the same faces, the same cities, the same visual languages. “People need to move out of Lagos,” Obaweya argues. “There’s so much landscape… so many monuments… but people are sticking to the same settings.”

The archive is still being formed. And as archival Nigerian fashion photography shows, what is recorded now will shape what can be remembered later. To move forward differently requires intention and an understanding that fashion images are not fleeting, but historical, and that keeping them is its own form of authorship.

.svg)

.png)