From Bethann Hardison to Katoucha Niane, these models have redefined fashion across generations

From the 1950s to today, Black models have shaped how fashion looks, and sit at the centre of fashion’s evolution, even as the industry struggles to move in step. Since the mid-20th century, they have shaped its imagery, expanded its imagination, and redrawn the industries boundaries. Their influence is embedded in fashion’s visual archive — visible everywhere, but frequently positioned at its margins. Across decades of shifting aesthetics and unfinished conversations about inclusion, Black models have continued to move the industry forward, often with recognition lagged behind their labour.

With the rise of fashion media in the 1950s to today’s hypervisible landscape, modelling has operated within narrow definitions of beauty and belonging. Agencies, designers, and editors repeatedly privileged a singular body type and skin tone, turning exclusion into structure rather than exception. Within these limits, Black models carved out space. Through presence, precision and refusal, they expanded what fashion permitted itself to see. Black models have carried fashion forward visually even as the industry resists moving with them structurally. Their labour has widened the language of beauty, challenged the geography of luxury, and forced the industry into conversations it routinely tried to defer.

Naomi Campbell and Iman reshaped the global runway, scaling Black visibility at a time when access remained tightly controlled. Beverly Johnson altered the politics of fashion media after becoming the first Black woman to appear on the cover of American Vogue. Others shifted the industry no less decisively — from Mounia becoming Yves Saint Laurent’s first Black muse to Alton Mason walking for Chanel, rewriting the codes of luxury from within.

These moments established foundations. They altered the terrain, allowing younger generations — the faces now defining contemporary fashion — to arrive into a landscape already changed by those who came before them.Today, Black models move through fashion with a different kind of visibility. Their faces anchor campaigns, open shows, and shape seasons in real time, circulating endlessly across screens and runways. Their influence is clear, even as questions of power, authorship, and access remain unresolved.

Despite institutional inertia, Black models continue to reshape fashion’s visual language from within. From Adut Akech’s sustained presence on international runways to a new generation of African and diasporic models redefining casting norms, their work accumulates into something larger than any single season.

As Black History Month progresses, we are reflecting on the Black models who shaped fashion as we know it today across decades, and their sustained presence that moved through an industry that rarely moved in step.

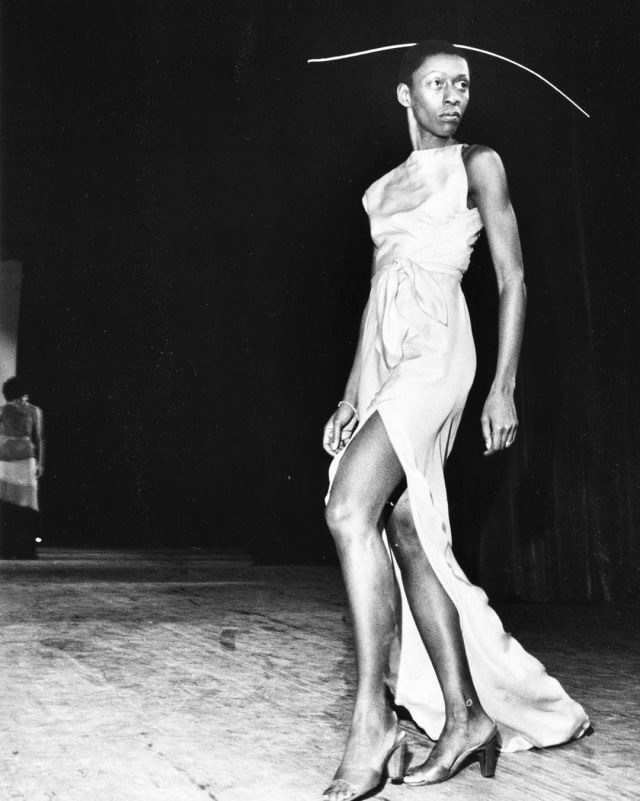

Bethann Hardison

Emerging in the late 1960s, Bethann Hardison became one of the first high-profile Black models in the U.S. Her early career reached a turning point in 1973 at the Battle of Versailles, a historic runway event that placed American designers and a group of Black models on an international stage. For many in attendance, it was the first time models of colour appeared on runways of this scale.

Hardison’s walk during Stephen Burrows’ segment became one of the evening’s defining images. Wearing a canary-yellow gown, she reached the end of the runway, dropped its train to the floor, and held her position, meeting the audience’s gaze without movement. The gesture disrupted the formality of the show and electrified the room. From there, Hardison’s modelling career accelerated within an industry that continued to treat Black models as exceptions.

By the mid-1970s, her work extended beyond the runway. Hardison moved into creative direction and production, collaborating with designers including Stephen Burrows, Kansai Yamamoto, Issey Miyake and Valentino Couture. Her involvement with Valentino connected her to Manifattura Tessile Ferretti, at the time a key swimwear licensee for leading Italian fashion houses, placing her within the mechanics of global luxury.

In 1980, Hardison joined the newly formed Click Models, where she helped reshape approaches to representation and career development. During her tenure, she worked with emerging talent who would later become industry fixtures, including Whitney Houston, Talisa Soto, Tahnee Welch and Elle Macpherson. Four years later, she founded Bethann Management, an agency built on an expanded understanding of beauty and opportunity. Beginning with seven models, the agency grew to represent more than seventy-five men and women across racial and ethnic backgrounds. The focus was structural presence and sustained careers rather than symbolic inclusion.

That same commitment guided her co-founding of the Black Girls Coalition in 1988 alongside Iman. Initially created as a space for connection and collective support among Black models working in high volume at the time, the group quickly evolved into an advocacy network. With members including Naomi Campbell, Veronica Webb, Karen Alexander, Roshumba, Beverly Peele, Cynthia Bailey, and others, the Coalition addressed issues ranging from racism in advertising to broader social inequities affecting Black communities.

Over time, Hardison became one of fashion’s most direct and consistent advocates, openly challenging designers, editors, and institutions to confront racial exclusion within their systems. Her work has continued to expand, encompassing runway accountability, support for emerging designers, and directing and film projects that examine fashion’s cultural power.

Her influence remains ongoing. Through decades of sustained intervention, Hardison has shaped fashion by insisting it accounts for the labour and presence it depends on. The recognition she has received throughout her career shows the scale of her impact and the enduring relevance of her voice.

Katoucha Niane

Born in Dakar, Katoucha Niane was a Guinean model and activist who entered fashion in the 1980s with a presence that resisted containment. Often referred to as the Peule Princess, she was among the first African models to move through European fashion at scale. Her career began in France, where she was first noticed by Jules-François Crahay at Lanvin. Initially hired as a fitting model, she quickly transitioned onto the runway. By the mid-1980s, Katoucha was walking for Thierry Mugler, who later made her one of the faces of his Spring/Summer 1988 campaign. Her work soon extended across the major houses of the era, including Azzedine Alaïa, Christian Dior, and Paco Rabanne.Katoucha’s presence reached a defining moment when she became the face of Yves Saint Laurent, succeeding Rebecca Ayoko and cementing her position within the highest tier of couture. As a muse to both Saint Laurent and Jean Paul Gaultier, she occupied fashion’s most rarefied spaces, and throughout her career, Katoucha refused the expectation that African models explain themselves. She moved through runways and magazine covers declining the burden of translation frequently imposed on Black bodies in European fashion.

In the mid-1990s, Katoucha stepped away from full-time modelling to explore other ventures, including launching a fashion line in Paris for a season. She later appeared as a juror on the French television programme Top Model and, in 2006, founded Ebène Top Model in Dakar. The competition was created to support and platform emerging African models and provide industry access.

Beyond fashion, Katoucha’s commitments extended into activism. She was a vocal advocate for women’s rights and dedicated significant effort to raising awareness around female genital mutilation. Through collaboration with non-governmental organisations and the founding of Katoucha Pour la Lutte Contre l’Excision in Senegal, she worked to advance education and protection for women and girls. Katoucha Niane’s legacy rests in the convergence of beauty, politics and conviction.

Naomi Sims

Born in 1948, Naomi Sims encountered repeated rejection from modelling agencies, some of which told her directly that her skin was too dark for their books. Rather than waiting for permission, Sims bypassed the gatekeepers altogether. Her breakthrough came through direct collaboration with photographers. In 1967, Gösta Peterson photographed her for the fashion supplement of The New York Times, marking a rare moment of mainstream visibility that reframed how Black women could be seen within fashion media. The image shifted perception, and momentum followed.

Soon after, Sims was selected for a national television campaign for AT&T, wearing designs by Bill Blass. The campaign propelled her into international recognition, and by the end of the decade, she had become the first African American model to appear on the covers of Ladies’ Home Journal and Life magazine. These milestones signalled a broader cultural shift in who could occupy the centre of American visual culture.

Sims’ influence extended beyond the runway. In 1973, she shifted from modelling to launch her own business, beginning with a wig line designed to reflect the texture and reality of Black hair. The venture was both commercial and corrective, responding to a market that had long continued to fail Black women.Sims also went into publishing. Beginning with All About Health and Beauty for the Black Woman in 1976, she authored several books focused on care, confidence and professional success with All About Hair Care for the Black Woman and All About Success for the Black Woman. This positioned her at the forefront, especially at a time when Black women were rarely addressed directly by the beauty industry.

Alongside her business ventures, Sims remained engaged with community work, supporting initiatives for young people, veterans and civil rights organisations. Across these efforts, she embodied a philosophy that extended beyond aesthetics. Her career asserted that Black beauty deserved visibility, investment, and care on its own terms. Naomi Sims helped establish a model of influence that reached past fashion’s surface. Through image, enterprise, and advocacy, she gave shape to the idea that Black visibility could also mean Black ownership, agency and self-definition.

Beverley Johnson

While studying at Northeastern University, Beverley Johnson began modelling during a summer break in the early 1970s, quickly securing editorial work that led to a steady rise through fashion media. In August 1974, she became the first Black woman to appear on the cover of American Vogue. This was a seismic shift in fashion’s visual politics and American editorial culture, and its impact was immediate. Within a year, Black models were appearing with greater frequency across U.S. fashion houses, showing a change in industry practice at the time.

Johnson’s career accelerated through the mid-1970s as she appeared on dozens of magazine covers, including a second Vogue cover and a solo cover for Elle, another first for a Black model. She moved fluidly between editorial and runway, working with designers including Halston, Ralph Lauren, Calvin Klein, and Oscar de la Renta.

Johnson transitioned into entrepreneurship early, developing beauty and hair ventures, and in the 1990s, she expanded into lifestyle branding. She has maintained a visible presence on the runway while turning toward advocacy. Through initiatives such as “The Beverly Johnson Rule” launched in 2020, she has continued to press fashion, beauty and media institutions toward measurable diversity commitments.

Iman

Discovered in the mid-1970s, Iman quickly became one of fashion’s most sought-after faces. Her work with photographers such as Irving Penn, Herb Ritts, and Richard Avedon placed her within the highest ranks of editorial fashion, while designers including Yves Saint Laurent and Gianni Versace embraced her as a muse.

Iman’s modelling career unfolded across runways and campaigns for houses like Halston, Givenchy and Chanel. She appeared on multiple Vogue covers and became emblematic of a shift in how African beauty could exist within Western luxury without explanation or performance. Yet even as she occupied fashion’s most elite spaces, Iman remained acutely aware of the industry’s racial mechanics. Having grown up in a country where Blackness was not marked as difference, she was struck by the way fashion insisted on categorising and limiting Black models as a separate class.

In response, Iman helped reshape fashion’s internal politics. Alongside Bethann Hardison and Naomi Campbell, she co-founded the Black Girls Coalition in 1988, an initiative that challenged tokenism and encouraged collective visibility over competition. The group’s work extended beyond symbolism and leaned into directly confronting designers and institutions when casting practices showed exclusion disguised as trend.

After retiring from modelling in 1989, Iman launched Iman Cosmetics to address the beauty industry’s refusal to cater to darker skin tones. The brand became both corrective and precedent-setting. Alongside her business work, Iman has remained deeply engaged in humanitarian efforts, serving as a global ambassador for organisations addressing emergency relief and health crises.

Naomi Campbell

Scouted as a child, Naomi Campbell’s career unfolded alongside the rise of the supermodel era, where she stood shoulder to shoulder with Cindy Crawford, Linda Evangelista, Christy Turlington, and Claudia Schiffer. Their collective presence defined fashion in the early 1990s, crystallised in moments like George Michael’s Freedom! ’90 video, which blurred the lines between runway, celebrity and pop culture. Campbell’s success was expansive in scale. She went on to work with nearly every major fashion house, appeared on hundreds of magazine covers, and in 1997 became the first Black woman to open a Prada show, shifting long-held hierarchies within European luxury.

Decades into her career, Campbell’s influence has only sharpened. In 2018, she received the CFDA’s Fashion Icon Award, acknowledging both her longevity and impact. In 2024, London’s Victoria and Albert Museum opened Naomi: In Fashion, the first major museum exhibition devoted to a single fashion model, placing her work within an institutional archive usually reserved for designers. Campbell’s career demonstrates how sustained presence can evolve into cultural authority, and expand the limits of what fashion is willing to preserve, celebrate and remember.

The groundwork laid by these earlier pioneers, and the generations after, have carried forward through figures who’ve expanded Black modelling into new forms of influence. Iman, through her beauty brand, exposed the industry’s long-standing failure to serve Black consumers, even as it continued to profit from Black aesthetics.

Bethann Hardison, Naomi Campbell and Iman together formed the Black Girls Coalition in 1988, which shifted conversations from inclusion as image to inclusion as practice — publicly urging major fashion houses to commit to using Black models at a structural level rather than as seasonal gestures. Beverly Johnson’s historic appearance on the cover of American Vogue marked another decisive shift. Her success with European designers such as Hubert de Givenchy and Yves Saint Laurent signalled a widening of fashion’s visual language, influencing casting practices as brands increasingly placed Black models at the centre of their collections.

Today, Black models continue this lineage from within the global fashion system. Their presence circulates across runways and campaigns in fashion capitals worldwide, shaped by a legacy built through decades of intervention and refusal. This presence, however, remains uneven and provisional. Recent Milan and Paris Fashion Weeks offer a clear example, where the return to narrow, racialised aesthetics at houses such as Dolce & Gabbana shows how quickly the industry reverts once scrutiny fades. Progress is still measured through moments and milestones rather than sustained shifts in casting power, creative control and authorship.Taken together, these figures show Black modelling as an ongoing practice of expansion, one that continues to reshape fashion’s visual language from within.

.svg)

.png)