People, as a result of living, inevitably face the consequences of being life’s actors. We see this manifest as individuals and more importantly, in our interactions as a collective. Though some of these consequences are beyond our control, others, like politics and power, come from our own making.

Admittedly, the tune that politics plays is one that everyday people in culture have learnt to dance to. Moving to the rhythm, they speak up in challenge or support of motions that are in their favour, choosing sides that align with their values and lashing out when politics and power struggles seem to be taking more from them than they are willing to give.

Yet, some actors have removed themselves from the dance altogether.

It is not unprecedented to see African creatives today show little concern to questions of social and political justice. As rapper, Tobechukwu Melvin Ejiofor, popularly known as Illbliss, put it, “there’s a huge percentage of the artistic industry that has basically turned their backs on what’s happening in Nigeria.”

Similar criticism echoed beyond Nigeria as fans called out Ugandan musicians for staying silent during a national protest, accusing them of “playing safe” at a time when voices mattered most.

On social media, frustrations often target stars like Burna Boy, whose global platform contrasts sharply with their domestic quiet.

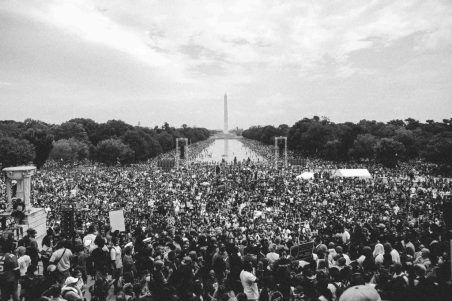

These moments reveal a widening gap between celebrity and citizenship; a gap once bridged by the politically conscious art of the #EndSARS generation.

Mr Macaroni, aka Adebowale Adedayo, and Falz the bahd guy, aka Folarin Falana leading peace walk to commemorate #EndSARS 3rd anniversary

Silence, theoretically, is viewed by Western and European scholars as ambivalent. It can take the form of resistance and power, but contextually, silence is evidently seen here as cultural dissociation and cowardice; a slow disintegration of culture.

When creatives, whose work shapes collective consciousness, withdraw into silence, culture itself begins to reverberate with emptiness. Art then loses its urgent ability to reflect the people’s pulse. In societies where creative voices once stood as the conscience of the people, this withdrawal feels like betrayal.

It is apparent today that African art has long lost the language of dissent.

From Fela’s revolutionary sounds and Chinua Achebe’s writings in challenge of colonialism to Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s prison writings, and many others, the fire that was once kindled against political and social injustice has slowly died out.

Truthfully, turning away from politics now is forgetting that our most resonant art was born from struggle, not silence.

Audre Lorde’s ‘Your Silence Will Not Protect You,’ and her insistence that refusing to speak out against injustice is itself a form of complicity, feels especially relevant today.

The attitude to keep silent as Illbliss noted, “…for reasons best known to them…”, signals to all who understand the impact of art on culture and society; of the creatives’ disturbing disinterest in anything beyond their art. This distances the creatives from their audience, eroding their moral connection and cultural relevance.

It is important for creatives to remember that in the context of culture's moral voice, the issues they contribute their voices to are equally, if not more, important than the art they create.

African creatives must return to the truth that art is not just expression but also advocacy. The microphone, the camera, the brush, the stage all stand as tools for witness.

And perhaps the question is not whether creatives should speak, but whether they can afford not to because the real risk lies not in speaking up, but in saying nothing at all.

.svg)

.png)