In one room, a concave screen cycles through a panorama of an abattoir’s outdoor workshop. The sound of the blade slaughtering animals is a backdrop to the periodic switch between a blood red filter and the stark brightness of reality. In another room, sweat trickles down the flesh depicted in a close up shot punctuated by strained grunts and moans. The final room is a stark contrast to both. Waves and palm trees occupy one screen while the other illustrates the loving care between a man and his horse. King of Boys (2015), MUSCLE (2025) and Cowboy (2022) make up the triptych of Karimah Ashadu’s first institutional solo show, Tendered, in London’s Camden Art Centre.

Ashadu’s practice has long featured the intricacies of Nigeria’s lower classed labour force. From her four minute insight into the labourers and hawkers of Lagos Island in 2012 to Lagos’ weightlifting community in MUSCLE (2025), Ashadu’s work is fixated on Nigeria’s most invisible population. Tendered covers a decade-long snapshot of this fixation in her work, curated by Fondazione In Between Art Films's Alessandro Rabottini and Leonardo Bigazzi. MUSCLE (2025) was commissioned specifically for the exhibition, accompanied by the sculpture works Cotch I & II (2025) and Pure Rugged Water (2025), both of which bring key motifs of the film into physical reality.

Room 1’s King of Boys (2015) is a five minute documentation of butchers at an abattoir rhythmically hacking at the carcasses of animals. The concave screen, panoramic rotation of the scene and the periodic switch between a red filter (created by a discarded bottle) and reality, distorts the audience’s experience of the film. The butchers and passersby are seemingly unaware of the camera’s presence, they simply carry on with the ordinariness of their activities. With the constant shift between the normal scene and the filter, viewers remain purposefully untethered rather than immersed into the scene. This is almost disquieting to experience, particularly in comparison to the popular need to integrate audiences into film as participants rather than observers as Ashadu does here. Watching from the colonial heart of Nigeria in the UK adds to the uncanny nature of this detached viewing experience.

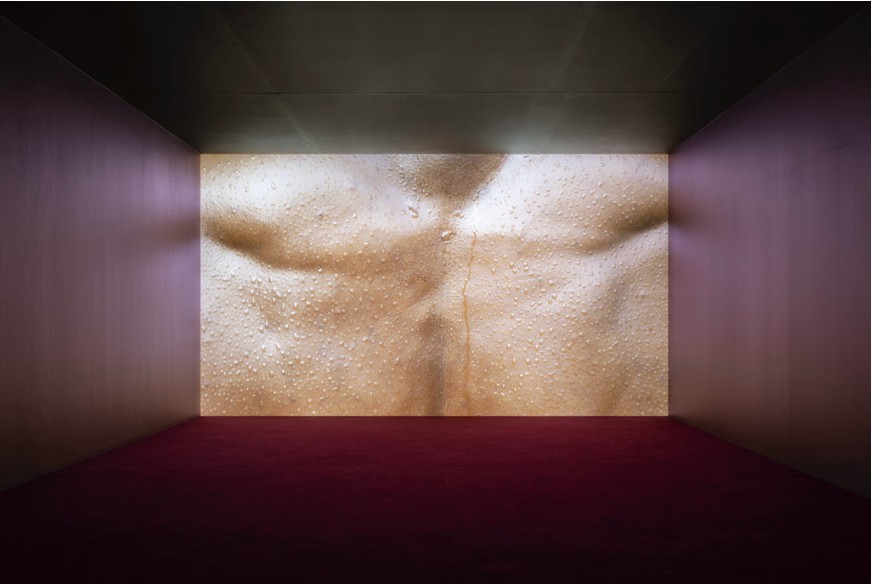

MUSCLE (2025) is a stark contrast to the detachment of King of Boys (2015). Rather than holding its audience at arms length, MUSCLE (2025) is shot almost entirely at close proximity to its subjects. Brown flesh and rippling muscles occupy the screen at a distance that makes it difficult to identify the exact part of the body on display. When the camera does give room to showcase the weightlifter’s faces, their expressions are marked with the exertion and focus of their tasks. Featuring Lagos’ community of recreational bodybuilders, Ashadu aims to portray “the weight of expectation” and “their particular performance of masculinity” as it verges towards hypermasculinity. Narrated by the bodybuilders themselves entirely in Yoruba, the film’s score is their grunts and moans of exertion that express the sensuous nature of their chosen activity. The narrators express how weightlifting liberates them from being troubled by area boys and thugs, suggesting that the hypermasculinity of the sport is rooted in self preservation rather than toxicity. Despite this, it is clear that their sense of manliness is tied to the inherent masculinity of the sport itself as one comments, “I look at people who do not lift weights. How do they live? One who doesn’t exercise, does nothing, only to wake up, eat and sleep, and have sex with their wife.”

The dual screened Cowboy (2022) is a juxtaposition to its predecessors in the exhibition. Ashadu’s camera follows a groom from land to sea as he professes his deep and enduring relationship with horses. The intimacy here lies in the man’s words rather than the close proximity, or lack thereof, of the camera with its subject. Both chronologically and thematically, Cowboy (2022) sits in the middle of its counterparts. The sound of the sea and the images of the ocean and palm trees on the second screen accompanies the gentleness and care portrayed in the primary screen. The cowboy’s narration is passionate yet soft as he describes his mixed heritage as a Nigerian Arab and his journey to Lagos from Saudi Arabia by horse truck. Horses are a lasting presence in the internationalism of his story. In the final shot, as the man pauses on his horse at the edge of the ocean, trade ships sit in the distance, potentially hinting at the colonial trade passages that have shaped Nigeria as a whole as well as his personal journey.

While each film differs in their compositions and themes, Ashadu ties Tendered together through their shared depictions of labour in Nigeria. Ashadu toys with the audience’s connections with each film, pulling us into a closeness that is nearly uncomfortable then keeping us at an observational distance. The context of Nigeria’s colonial relationship with the UK feeds into this dichotomy, particularly in King of Boys (2015) but also in the nature of the black male body as a spectacle for viewers in MUSCLE (2025). Although MUSCLE (2025) is the specific commission for the exhibition, Cowboy (2022) leaves a lasting impression in its soft, thoughtful composition. Overall, Tendered is a testament to the growing collection of Karimah Ashadu’s cultural commentary on the unseen side of Nigeria’s labour force.

.svg)

.png)