Taiwo Adeyemi spent nearly a decade managing individual creative careers before he began asking a deeper question: what if the real bottleneck isn’t talent, but the infrastructure around it? Through BoxxCulture, he helped film icon Nse Ikpe-Etim leverage her platform to advocate for women living with adenomyosis, guided chess world record holder Tunde Onakoya through raising a million dollars for children’s education during his Guinness World Record marathon, and created Road2Blow; a documentary series that highlights the struggles talents endure on their journey to fame in the Nigerian entertainment scene.

The work proved something important: you can connect visionary people to global stages. But the question that led to Polygon, the creative space he launched in 2024, asked for more. How do you build an ecosystem where those connections happen organically, repeatedly, and at scale?

.png)

A year in, the answers are taking shape, and Polygon doesn’t resemble a traditional creative hub. Its thesis isn’t built around desks or events; it’s built on designing for sustained co-creation. Polygon’s six first principles: space, access, collaboration, affordability, partnership, and flow function as operational filters. Every program is tested against whether it makes room for people who typically don’t have it, and whether it increases the kind of network density where photographers introduce designers to strategists, where musicians discover visual artists, and where passing conversations turn into long-term projects. That’s infrastructure, not community management.

.png)

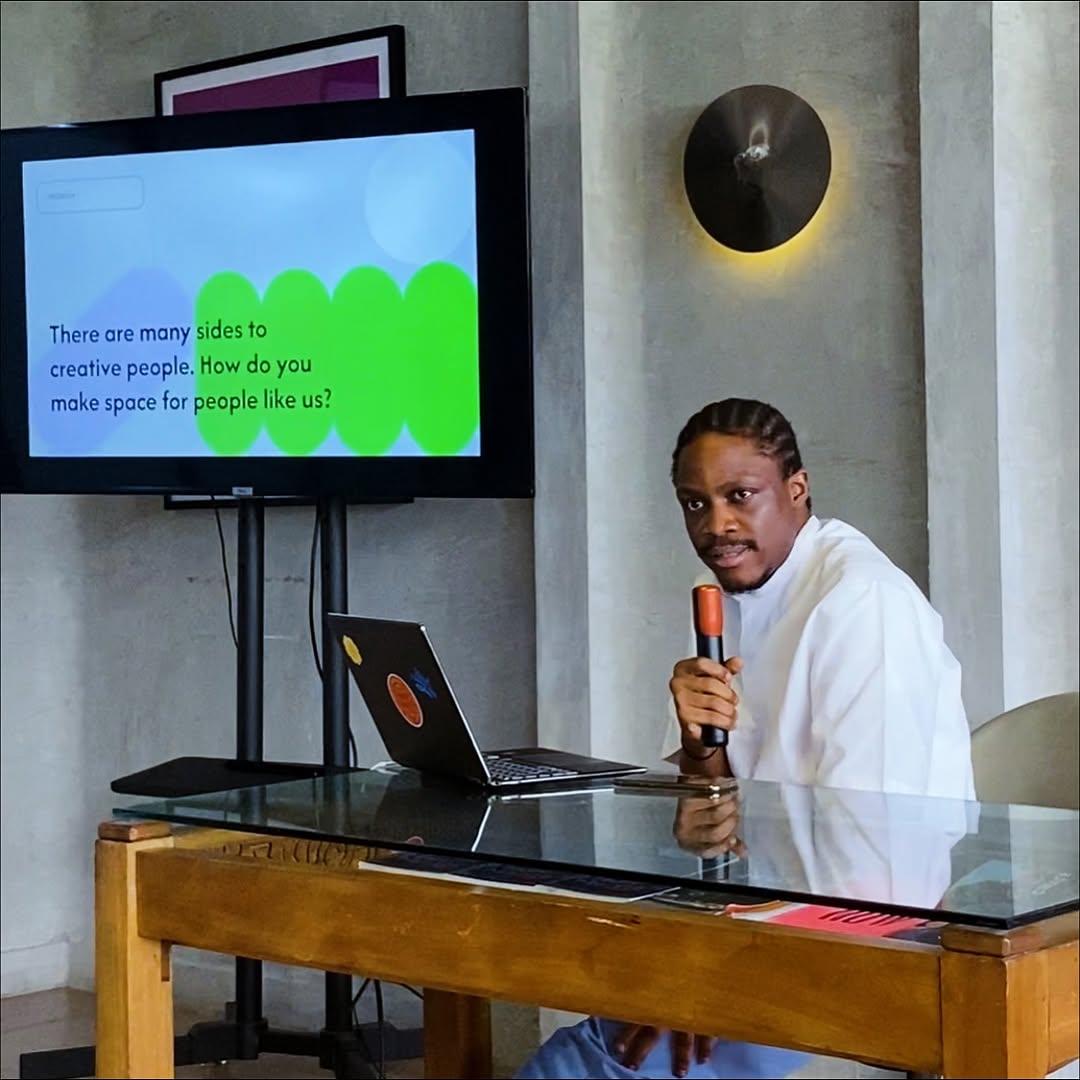

The first anniversary event on October 30 2025, themed “Make Space,” brought this thesis to life. Adeyemi opened the day with a reflective presentation to partners and the People of Polygon, tracing the evolution of the space and revisiting Polygon’s first principles. The morning set the tone: this is a creative ecosystem, not a venue. Conversations spilled into a cocktail reception where collaborators explored what “the next shape” of the ecosystem should look like.

.png)

By noon, the day slowed into a wellness-centered session moderated by Angel Anosike, founder of Unpacked with Nay. Through mindful conversation, movement, and shared affirmations, the group examined gratitude as fuel for longevity, an antidote to the burnout cycle that shadows many creatives.

As evening approached, the community gathered around a long, communal table for a dining experience curated by La Soireé. Over shared plates and laughter, conversations circled around lessons from the first year, the responsibility of shared creative spaces, and what it means to build ecosystems that empower rather than extract. The celebration closed with a party anchored in music, art, and nostalgia.

Across the four sessions, one thing was clear: the People of Polygon help shape the culture that gives the space its identity. The recursive loop, where community contribution becomes community ownership, is the difference between a service and infrastructure.

Polygon’s next chapter makes its infrastructure thesis explicit. Polygon Social, the formalization of the network that already exists inside the space. The goal is to deepen collaborations, build a vibrant creative network, and scale Polygon’s impact across cities and disciplines through residencies, membership experiences, and new forms of communal connection.

Adeyemi’s own trajectory mirrors this philosophy. After dropping out of Civil Engineering to pursue graphic design, he built a multi-hyphenate career that led to his selection as a 2025 Skoll Fellow at Oxford’s Saïd Business School, joining 35 global changemakers. He now leads Losing Daylight, an initiative working toward Nigeria’s first museum dedicated to art and cinema history. His path reflects a different blueprint for African creatives, one that doesn’t follow the tired sequence of “go global, get discovered, come back.” Instead: build locally, partner sustainably, scale thoughtfully, and let the model travel if it’s strong enough.

Lagos already has dozens of co-working spaces. But Polygon isn’t selling location or amenities. Its differentiation lies in designing infrastructure around how African creatives actually work, not around a Silicon Valley template built for freelancers and founders. The bet is that creatives don’t only need WiFi and a desk, they need a physical environment engineered for collisions, collaboration, reciprocity, and long-term community.

That’s harder to mass-produce, which is exactly why Polygon’s expansion plans prioritize depth over square footage. More residencies. More connective tissue. More multi-city integration. A network built from the inside out.

If the model succeeds beyond Lagos, Polygon becomes a template for African creative infrastructure, one designed for collaboration from the ground up. A space where creative collisions happen consistently enough that people keep showing up, keep connecting, and keep building. This is exactly what the industry needs.

.svg)

.png)