Uzo Njoku, a Nigerian-born visual artist, holds a B.A. in studio art from the University of Virginia. She was also an MFA candidate at the New York Academy of Art. Her art is reminiscent of African heritage, particularly Nigerian culture. Her versatile skill set majorly presides on the creation of functional art. The pieces she makes are often replicable pieces of digital art, which are made into patterns and printed onto fabric, wallpapers, kitchenware, and signage. She has worked with several brands like Apple, Tommy Hilfiger, and Yves Saint Laurent.

Uzo started exhibiting her work in 2020, with group and solo shows in the United States and across Asia. In the second quarter of 2025, she announced plans to host her first African solo exhibition, Owambe, as her way of paying homage to her Nigerian roots. This admirable feat was made public after several months of planning, and personal funding. Despite her transparency concerning the exhibition planning, sponsorship, and aim, she received a fierce rebuttal, notably on Twitter, now known as X.

Digital mobs are a common phenomenon in the virtual space, mostly on social media platforms. They are inevitably formed when certain parties decide to influence the masses to follow their train of thought, often at the expense of another individual/group.

In Uzo’s case, she was accused of appropriating Yoruba culture for personal gain as a person of Igbo descent. Her work often involves the use of symbols, and she was accused of mixing Igbo with Yoruba signs and intentionally misspelling Owanbe as Owambe, claiming that the original spelling is the former.

The major force behind this virtual injunction was the Yoruba Progressive Elites Forum (YPEF), a group claiming to protect the Yoruba culture from expropriation. Other parties with the same interest fanned the flames of this discourse, garnering support with votes on a petition to stop the show’s hosting in Lagos as originally intended. This cause was further backed by legal claims and cultural interference by some traditional title holders indigenous to Lagos.

Despite the constant vitriol Uzo received, she continued to provide publicity for her work, engaging with the positive feedback and collaboration requests she received on X. She also doubled down on spreading accurate information about her intentions with the show, using her social media pages and eventual news platforms provided. In the spirit of making her exhibition every bit Nigerian, she introduced interactive measures to create an immersive experience for visitors.

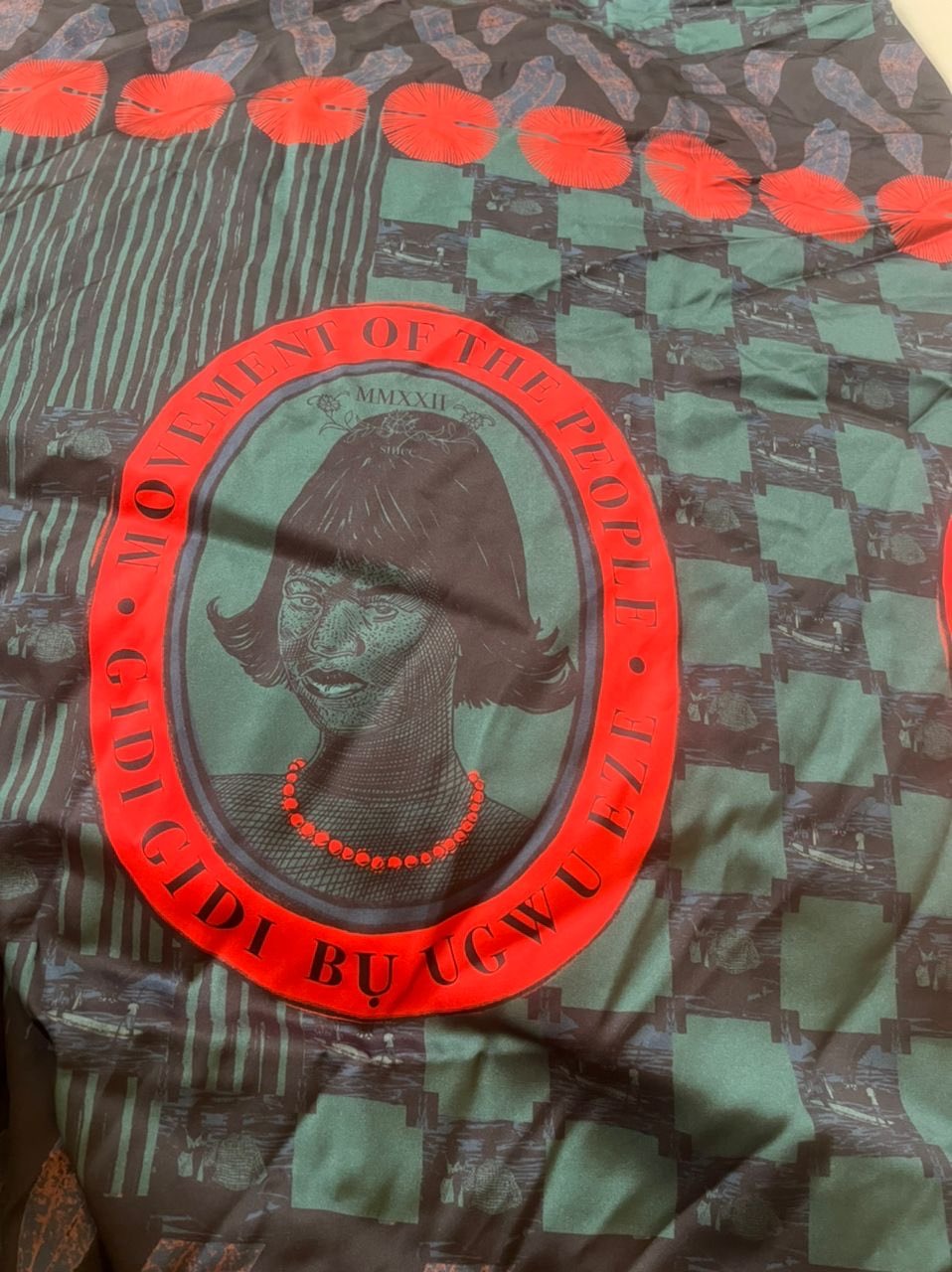

The fabric she made especially for the show, dubbed "Government of the People," was sold on her website weeks before the show opening, alongside potential outfit designs. This spurred the interest of many art lovers and individuals who naturally grew curious about her tenacity in the face of such menacing threats. On the set day, Uzo’s Owambe opened at a set location in Ikoyi, Lagos, with daily viewings set at UzoArt NG, Victoria Island, Lagos. Visitors came adorned in dresses made with the theme fabric. They had interactive sessions, including a draw-and-paint segment.

The show opening was a success, and testimonials from visitors attested to this fact. However, the malicious crusade did not cease. Some individuals clowned the event, mocking its simplicity and coterie. In her characteristic manner, she pointed out the reasons for it. The mechanism of these organized attacks pointed to a larger plot, alien to Uzo’s attempt to honor her roots through art. The socio-political sphere of the Nigerian-X (Twitter) community has been rife with tribalistic comments and bigoted acts, with the overarching aim of placing one tribe above the other.

Owambe is beyond an art show. It speaks to the artist’s vision to document Lagos’ vibrant culture through art. It also reflects her determination to create and inspire beyond the unexpected obstacles she encountered.

.svg)

.png)