Nigerian-British poet, filmmaker, and photographer Caleb Femi’s debut collection, POOR, has already left an undeniable mark on contemporary poetry. Femi, the first Young People’s Laureate for London, saw the book first published in the UK in 2020. The book went on to win the Forward Prize for Best First Collection and received widespread critical acclaim, appearing on multiple year-end best-of lists across British media. Now, with the release of its American edition set for January 27th 2026, POOR enters a new phase of its life.

Deeds Magazine sat down with Femi to unfold the layers of youth, masculinity, and survival in South London that shaped POOR, and to consider how the work resonates in conversation with American literary traditions.

.jpg)

Caleb, welcome back! We were last in New York for the launch party of The Wickedest, when you mentioned working on five things at once. Before we unfold the US release of your debut, tell us, in your own words, what have you been up to over the past year?

I remember that night in New York fondly. Since The Wickedest launch, life has been a whirlwind of creativity. Over the past year I’ve been fully focused on getting my concept hub SLOGhouse off the ground. SLOGhouse is a creative space – a kind of ideas laboratory – where my team and I take concepts from a spark of inspiration through to full realisation. Most importantly, like everyone else in these challenging times, I've been learning how to breathe and find balance in a world that sometimes makes it difficult.

I remember how I felt when POOR was first introduced in the UK, and now reading it again, it is almost like revisiting an old friend. After five years and numerous awards, why do you believe it is important, now more than ever, for this work to be brought back to light and to an American audience?

It’s amazing to think it’s been five years since Poor first came out. Back in 2020, the book spoke to a moment and a place but the core themes have only grown more resonant since then. In the years that followed, we’ve all lived through some pretty seismic changes: a global pandemic, a louder global conversation about racial injustice, and ongoing struggles with inequality. Poor was always about giving voice to experiences of community, race, class, and hope within hardship. Now, more than ever, those conversations are alive worldwide, including in America.

Bringing Poor to an American audience at this moment feels timely and important because the themes in it aren’t just British – they’re universal. I want Poor to reach people who might see their own stories reflected or at least gain insight into lives that mirror struggles in their own cities. The issues of disenfranchised youth, of finding joy and magic in tough circumstances, of grappling with the legacy of structural inequality – these are as relevant in Chicago or New York as they are in London. Sharing Poor with American readers now, after it’s matured and gathered energy over five years, is like reopening a dialogue. My hope is that it sparks fresh discussions and connections in a context that, while different, has its own very similar echoes of the world I wrote about.

Looking back, I’m sure you feel as though you were a completely different person in 2020. If not, then at least a younger version of yourself. What is apparent to you now that wasn’t then?

The Caleb who wrote Poor in 2020 was hungry to express a very specific slice of life – I poured my heart into capturing my youth in Peckham, the pain and beauty of it. Now, five years on, I can say I’ve grown and my perspective has broadened. One big thing that’s apparent to me now, which I maybe didn’t fully grasp back then, is that there are even more wonderful things in the world to experience than I had imagined. Back then I thought I understood the breadth of life – the struggles and the joys – but traveling, meeting people from all over, and pushing myself into new creative arenas has shown me that my world is so much larger than I thought it was.

That perspective keeps me humble and excited for what’s next.

When I spent time in New York this summer, I was struck by how differently readers interact with books compared to Europe. Here, literature feels deeply community-based – from bookstore bars to book clubs and retreats. In Harlem, for example, you’ll come across authors who take to the streets not only to sell copies but also to interact directly with their surroundings. With that in mind, American readers are encountering POOR in a different cultural context. What conversations do you hope the book sparks here that might be distinct from those in the UK?

That’s a fascinating observation, and it gets me excited about Poor finding a home in this different literary ecosystem. Honestly, the conversations it might spark in the US are the great unknown that I’m really looking forward to discovering. Every community will interpret a story through its own lens. In the UK, Poor sparked conversations about council estates, youth clubs, and the specific dynamics of London’s changing neighbourhoods. In the US, I hope readers will bring Poor into their own community contexts – maybe it’ll resonate with people in the Bronx, South Side Chicago, or Oakland in ways that I can’t fully predict. I’m eager to see the book take on a new life with new layers and intersections in America.

One thing I’ve always intended with Poor is for it to be a conversation starter rather than a prescriptive statement. The book was meant to be part of a trans-global conversation about the experiences of marginalised communities, not a didactic text that tells people what to think. I didn’t write it to control or shape anyone’s narrative. I wrote it to share a piece of my world and invite others to share theirs in response. So if American readers start discussing parallels between Peckham and, say, Brooklyn or Detroit – or even if they debate differences – that’s fantastic. I hope Poor inspires people to talk to each other about their own communities. The best outcome is if it encourages community storytelling, people saying, “This reminds me of my neighbourhood,” or asking, “How do our experiences overlap or diverge?” Those are the organic, grassroots conversations I’m excited to see unfold.

POOR touches on subjects of belonging, grief, boyhood and much more. In your opinion, are there aspects of the American experience or literary scene that mirror the world you depict in POOR?

Absolutely. Even though Poor is grounded in the specifics of South London, it asks readers to zoom out and consider the collective experiences of working-class cities throughout the West. Many American cities share the same stories at their core. The book is, in many ways, an indictment of the same forces that shape urban life in America: the legacy of colonialism, the grinding gears of capitalism, and how those play out in architecture and environment.

Within Poor, everything is filtered through the framework of Black youth culture in a London estate. But if you strip away the place-names, the essence could be the story of kids in any number of American cities. There’s a shared resilience and creativity I’ve seen in both British and American youth communities. Hip-hop was born in the Bronx and found an echo in London’s rap scene – young people on both sides of the Atlantic use music, style, and language in similar ways to survive the concrete jungle. So yes, the American experience has many mirrors to what I write about. Readers in the U.S. will see parallels in the systemic challenges, things like over-policing, underfunded schools, or gentrification, and they’ll also recognise the joy and vibrancy that come with making the best of limited resources. The U.S. literary scene has long grappled with these themes too, so I think Poor enters a conversation American writers and readers are already engaged in, reinforcing that these struggles and triumphs transcend any one city or country.

British and American poetry traditions share a lineage but often speak in different cadences. What, if anything, do you admire or absorb from U.S. poets past or present?

I’ve always felt that I’m in conversation with poets from everywhere, and American poets have been a huge influence on me. In fact, in Poor I directly nod to a few American voices that mean a lot to me. I quote lines from poets like Joshua Bennett, Claudia Rankine, Nate Marshall, and Terrance Hayes within the book. Each of these writers brings something unique that I admire.

There’s a long history of British writers finding new meaning for their work when it reaches America, from Baldwin’s time in Paris to grime artists performing in New York. Have you felt that same sense of reinterpretation or renewal while bringing POOR across the Atlantic?

Yes, absolutely. Even as Poor is just now formally releasing in the U.S., I’ve already felt a kind of renewal in the process of bringing it here. It’s a bit like hearing a song you wrote being covered by someone else – you suddenly pick up on different notes. When I share poems from Poor with American audiences, I notice they react to things in ways that London audiences might not, and that in turn makes me see my own work differently. Certain references or slang that are commonplace in South London might prompt curiosity or a fresh understanding here. That reminds me that literature lives and breathes differently depending on where it lands.

If POOR began as a love letter to South London, what kind of letter does its U.S. release feel like now? A conversation, an invitation, or maybe a continuation of something larger between two creative worlds?

I’d say the U.S. release of Poor feels less like a single letter and more like I’ve entered into an ongoing conversation, one that crosses the ocean. It’s as if that love letter to South London has grown up and found a pen pal overseas. When Poor was just in the UK, it was my intimate message to my home. Now, bringing it to America, it feels like I’m opening that message up and saying, “Alright, your turn, how does this resonate with you, and what can you tell me about your home in return?” So it’s definitely a two-way conversation. American readers will bring their own experiences to it, so the book becomes an invitation to dialogue.

It’s also a continuation of a larger dialogue that’s long existed between creative communities in the UK and the US. We’re often grappling with similar core questions – like how we got here as a generation and where we go next. The release of Poor here adds another voice to that transatlantic discussion. It’s adding a London perspective into American narratives, and in doing so, it carries forward a shared story about working-class life, inequality, art, and hope on both sides of the pond.

When American readers land on the final page of POOR and close the book, what do you hope stays with them from literally a chapter of your life? Is it a feeling, a question, or maybe a kind of recognition?

More than anything, I hope they walk away with a sense of recognition – a feeling that, even if the specifics of my life in South London are different from their own story, there’s a common human heartbeat between us. Whether a reader is a young person in Atlanta or an elder in Seattle, I want them to recognise some part of themselves or someone they know in these pages. That recognition can breed empathy: maybe someone from a very different background finishes the book and feels like they’ve lived a bit of my life, or sees their neighbours’ struggles in a new light. That would mean a lot to me.

I also hope there’s a feeling of catharsis. Poor doesn’t shy away from grief, anger, or loss. I delve into painful memories and the weight of injustice, but I do it to unearth those emotions and share them. If a reader goes through those poems and feels a release then it’s done one of its most important jobs. And tied to that catharsis, I’d love if readers feel a surge of invigoration, a kind of inspired momentum to keep moving forward. Despite the heavy themes, Poor is also about hope and resilience, about finding magic in the margins. So ideally, closing the book leaves someone not in despair but galvanised, asking themselves what they can do in their own world or simply feeling less alone in their fight. Whether it’s a question about societal change or just the subtle uplift of having been understood, I want that final note to energise them. In essence, I hope Poor gives its readers a mix of recognition, relief, and resolve.

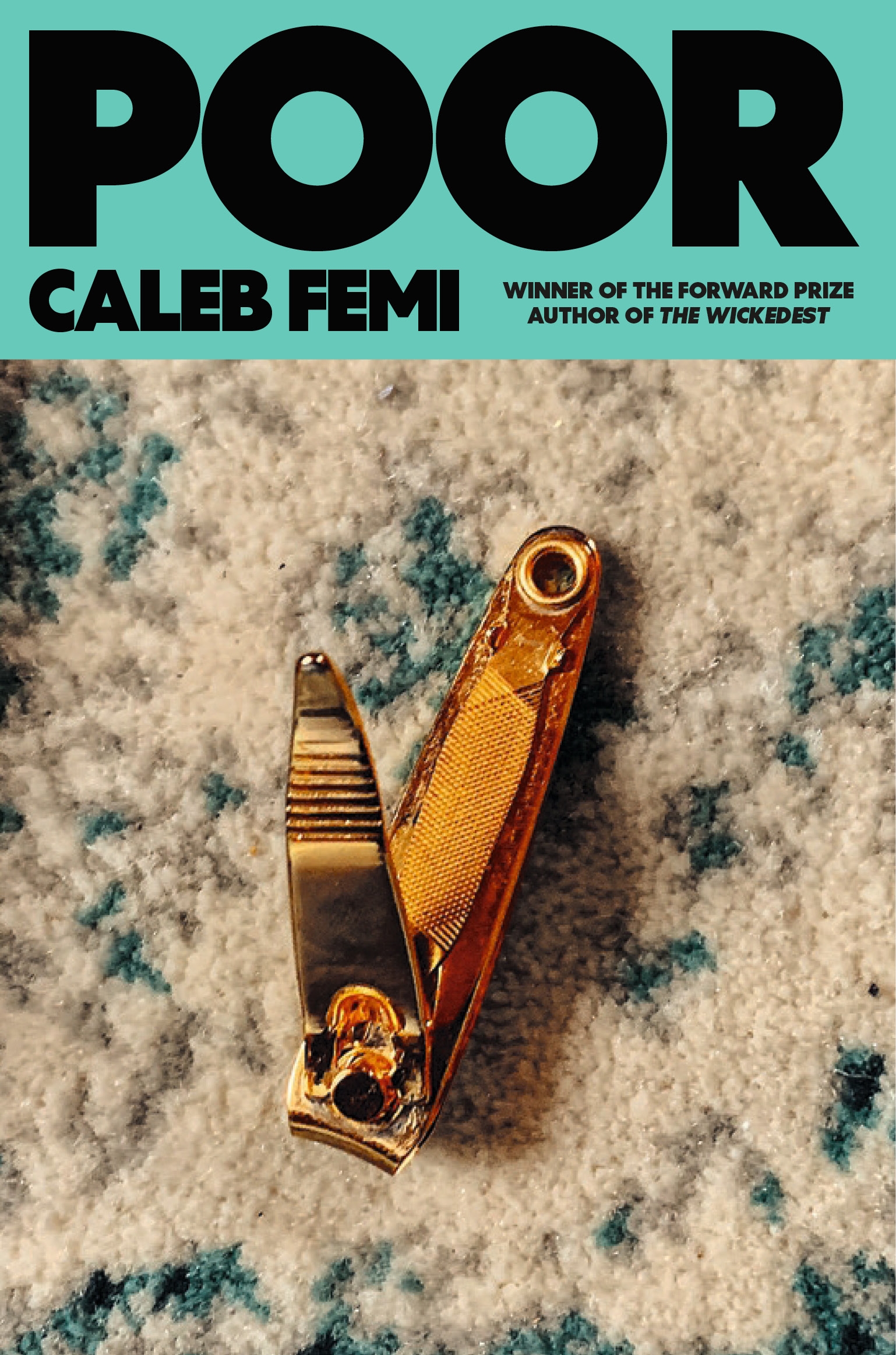

My final question is more out of curiosity on my end: out of all the photographs accompanying your poems, what led you to choose the nail clipper for the cover? And what does it signify to you?

Ah, the golden nail clipper, I love this question. That nail clipper is a humble, everyday object, something virtually everyone owns or has used. In the homes I grew up around (and certainly in my own household), a nail cutter was a staple item you’d find in a drawer or bathroom shelf. It’s mundane and ordinary, and that’s partly why I was drawn to it. I wanted the cover image of Poor to be immediately relatable – something anyone might recognise and have a memory of. At the same time, the nail clipper being gold is intentional.

For me, the gold nail clipper hints at finding luxury or value in the everyday. In communities that are economically poor, there’s still a rich sense of style and pride. People might not have much, but they often have one object that brings a bit of sparkle, a little symbol of aspiration or taste. A nail clipper works the same whether it’s gold-plated or plain steel, and that’s the point: making it gold doesn’t change its function, but it speaks to our desire for beauty and status, even in small things. So that image encapsulates a lot of what Poor is about, ordinary people with big dreams. It’s an everyday tool dressed up like treasure. I thought that was a fitting emblem for the book, and I hoped it would make people pause, maybe smile, and think about the mix of hardship and hope inside.

Related articles:

Exploring ‘The Wickedest’ at Caleb Femi’s Book Launch in NYC

3 Poetry Books You Should Read This Black History Month

.svg)

.png)